This piece is inspired by curiosities surrounding Aviary’s release 006: Jhon Didier Trujillo, which is available in limited quantities through the Aviary website. To support this blog and the work I do—and to place this piece in context of the coffee that inspired it—please consider ordering.

Things aren’t always what they appear to be: a truth that serves both as a lighthouse and a siren—and one that feeds my fascination with coffee.

When I started working in coffee nearly 15 years ago, baristas were still taught that coffees were associated with certain flavors specific to the region from which they originated. Provenance had its place in a café and on a roaster’s menu, understood to be more deterministic than heuristic. As a young buyer, I became obsessed with finding coffees that defied this conventional wisdom—Colombians masquerading as Kenyans, Nicaraguans impersonating Ethiopians. And as I continued to work in coffee, the subtleties of processing added a delicious layer of surprise: naturals could taste clean and bright, and washed coffees could be fruity and sweet.

Flavor memory is at the heart of what we do in coffee and is the basis for how we construct an understanding of both quality and our aesthetic preferences. We pattern-match based on our experiences and learn what we like and don’t—which processes we skip, and which cultivars we seek out.

As we build a mental catalog of these coffees we’ve tasted, we categorize each one and build a hierarchy or taxonomy based on apparently similar coffees we’ve had before. And so our understanding grows more sophisticated and nuanced, and after a while, we begin to notice coffees that deviate from expectations or don’t fit our understanding.

Coffee buying lives in the gray area between the knowable and unknowable—and our ability to detect and discern can make us better buyers, or, when programmed with bad information, lead us crashing into the rocks.

But I prefer replicable experiences—and my style and strategy of coffee buying is about increasing the odds that when I find something I like, I’ll be able to find it again. And because I have built a framework for coffees based on my experiences, I’ll better be able to understand how to approach a known coffee for analysis or roasting.

I like knowing what a thing is; I like to be certain.

In March 2001, a federal court sentenced Michael Norton to 30 months in prison on charges of fraud and tax evasion relating to his scheme of repackaging cheap coffee from Panama in “Kona” bags and selling them at a premium. At the time, while Panamanian coffee sold for $1.80-2.50 per pound, coffee from Kona, Hawaii sold for $6-8. It didn’t bother Norton that traders worldwide sold roughly 10 times more “Kona” coffee than the small island actually produced—it wasn’t trademarked, after all. In the days before the third wave or before the term “single origin” got attached to coffee, all that a coffee had to do was be apparently similar to pass as the same.

But it wasn’t the same.

“I could tell right away,” Carl Jones told me in February of this year as I sat across from him at his house in an inner-ring suburb of Cleveland. Carl was an early pioneer of specialty coffee, founding Arabica Coffee in Cleveland in 1976 with a couple of Royal peanut roasters and a Probat that looked like it was built before the war. A couple years later, during his company’s rapid ascent, he’d go on to be part of the steering committee for what-would-become the SCA. “I called him up and said, ‘What is this shit? Why are you trying to sell me coffee from Boquete and say it’s from Kona?’ It was obvious. Back then the coffee from Panama was shit, and it all had a very distinctive taste of gunmetal. Coffee from Kona didn’t.”

Twenty-three years after Norton’s sentencing, coffee farmers from Kona recovered more than $41 million from distributors and retailers selling counterfeit Kona coffee following a 2019 lawsuit filed by a coffee farmer against 20 companies. The lawsuit relied on a chemical analysis method that examined the concentrations of rare inorganic compounds in coffee that remain stable during the roast. As reported by the New York Times:

After testing coffee samples from around the world as well as more than 150 samples from Kona farms, Dr. Ehleringer’s team identified several element ratios — strontium to zinc, for example, and barium to nickel — that distinguished Kona from non-Kona samples.

Researchers compared the coffee sold by the defendants against the chemical fingerprint they’d built, discovering that many of the coffees labeled as “Kona” by the distributors were, in fact, not from Kona.

These cases are unusual; not just in the audacity of their perpetrators, but in the criminal, intentional way that provenance was exploited by resellers to increase the marketability or value of a less-valuable coffee. Most of the time, though, when coffee is mis-identified, it’s neither criminal nor intentional.

But however it happens: a thing isn’t always what it appears to be.

Coffee farmers planting trees on their farm typically obtain seeds or seedlings through government-supported seed banks and nurseries or local nurseries. In the best case, these purveyors ensure that the types of coffee trees they sell are well-adapted to the region and offer attributes desirable for local coffee producers. Because the movement of plant material between countries is subject to international regulations, it’s difficult, for example, for a farmer in Papua New Guinea to come across Gesha seeds or seedlings, unless that material arrived to PNG through “unofficial” channels—that often, curiously, represent backpacks favored by coffee buyers and roasters. Local bottlenecks and limited availability results in a certain density saturation of cultivars within growing regions, particularly as those cultivars gain favor with buyers.

Pink Bourbon, which was first discovered in the 1980s near Acevedo in Southern Huila, first grew in popularity among farmers because of its apparent resistance to roya, which first arrived in Colombia in 1983. Initially believed to be a natural hybrid between Red and Yellow Bourbon that produced orange- or salmon-colored cherry, the tree was often planted in mixed blocks of other varieties. But when buyers later learned that the tree could produce coffees of exceptional quality, they began to pay a premium for separations of Pink Bourbons and seek out producers who grew the strange tree. Producers, too, took notice. Around the time that I first tasted Pink Bourbon from Palestina, planting of the tree exploded around Acevedo, Palestina and San Agustín using seedlings from local sources and creating a concentration of Pink Bourbon from these areas. By 2021, 6 of the top 23 coffees in the Colombia Cup of Excellence were Pink Bourbon from Huila.

Through genetic fingerprinting—first conducted, to my knowledge, for Caravela Coffee in 2017 and then again later replicated by Café Imports—we would later learn that the tree we called Pink Bourbon was in fact not Bourbon at all, but an Ethiopian landrace.

It wasn’t what it at first appeared to be.

Because new trees came from neighbors or from local nurseries typically using traditional methods of selection and breeding and because young coffee trees can be visually difficult to differentiate (especially before they fruit), sometimes those seedlings are mis-identified—first by the nursery, and then by the producer, and then by the buyer, all inadvertently and without any intention to deceive.

This fact wasn’t lost among buyers, for whom the sentiment of “not all Pink Bourbons are created equal” took hold alongside the existing feelings about variations in Gesha coffees..

A pair of 2024 publications by World Coffee Research seemed to support this suspicion.

In the first, a Quality Assurance Report, WCR described their findings testing seeds across 52 seed banks in 5 countries in Latin America. The study revealed that:

36% of participating seed lots showed “very high rates of genetic noncompliance,” meaning 50% or fewer tested coffee plants were being correctly identified, according to genetic testing. The report attributes such results to a lack of good agricultural practices (or GAPs) as well as structural challenges such as lack of certification tools and profitabililty/investments.

In a second report, WCR evaluated the quality of coffee produced by trees of identical genetic makeup across their study sites, “testing 31 top-performing coffee varieties across 28 testing sites in 16 countries worldwide.” They found, somewhat unsurprisingly, that “many of the varieties evaluated may be better tailored and more responsive to the conditions of specific growing environments, and the same coffee varieties grown in similar environments regularly produced similar cupping results.” Some varieties, though, “produce higher rates of variation in cupping scores across different environments and evaluation periods.”

So maybe there’s something to it after all—perhaps not all Pink Bourbons are created equal; and perhaps not all Pink Bourbons are, in fact, Pink Bourbon.

When Carmen Cecelia Montoya and her brother bought land to grow coffee in 2008, it wasn’t yet planted. They’d need to build infrastructure—a warehouse, a washing station—and they’d need seeds.

They planted their farm using seed they’d gotten from a neighbor, Oscar Tavares, without really knowing what it was. Carmen had been a coffee picker on many of the farms in the region and knew the coffee trees on Oscar’s farm well—short in stature, and producing fruit in dense clusters along nodes on each branch. For a picker, it made efficient, profitable work; for a grower, it meant high yields even from a small amount of land.

Caturra from Jhon Didier Trujillo’s farm in Urrao taken June 19, 2024 of a Caturra Chiroso bearing fruit; notice the dense clusters of olive-shaped or elongated beans.

In 2011, Carmen began to produce cherry and sold coffee to the local cooperative. The buyer there, after learning where she lived, asked if she was a neighbor of José Arcadio, a well-known and well-respected second-generation coffee grower in San Carlos. José is her neighbor—and so the buyer identified the coffee as Caturra. But while her trees were similar in stature and productivity to Caturra, Carmen noted that her coffee produced elongated fruit—almost like an elongated Caturra. She called it Caturra chiroso—a reference to a popular Huilense snack food that the fruit resembled.

In 2014, Carmen won the Cup of Excellence; Jose Arcadio placed 11th. Since then, we’ve seen the meteoric rise of Chiroso, in both of its apparent variations—the taller Bourbon Chiroso and the more compact version grown by Carmen.

Of course, as the refrain goes: things aren’t always as they seem.

A 2021 study appearing in Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution used PCR testing to conduct gene mapping of 137 samples of Coffee arabica from known Ethiopian accessions, worldwide cultivars, and Yemeni germplasm—selections which included Chiroso. Introduced in the study as “a variety grown in Colombia and said to have a superior cup quality,” the study revealed that Chiroso was, in fact, “part of those Ethiopian landraces that ‘escaped’ Ethiopia.”

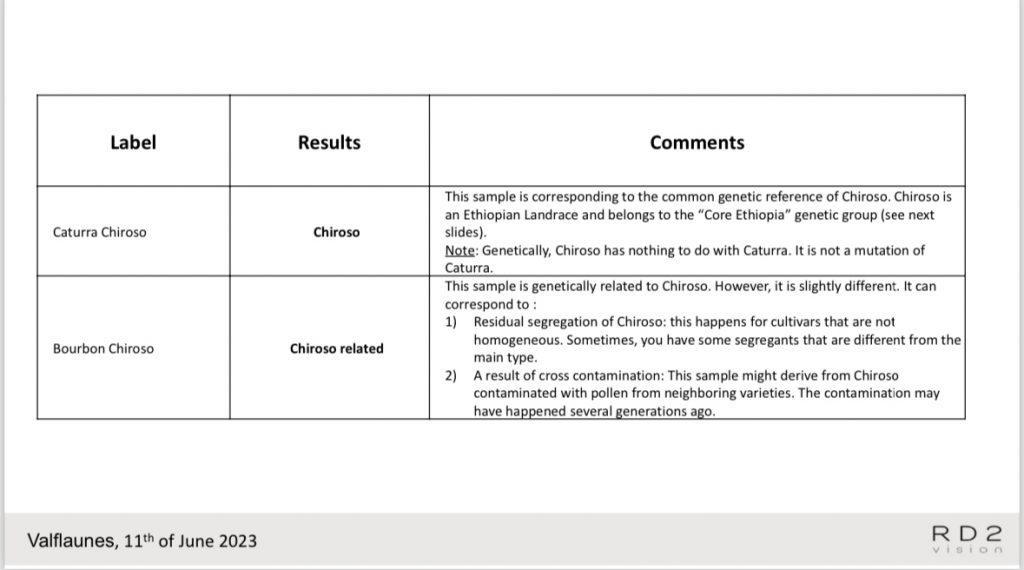

That same year, Jhon Didier Trujillo decided to plant coffee at his four hectare farm in Urrao. He chose to use seeds the tree that had become famous not only in the region but among buyers—planting 5,000 Caturra Chiroso trees below lulo and banana trees. Gene fingerprinting conducted by RD2 Vision in 2023 in a collaboration between Sey and Unblended mirrored the findings of the 2021 study, revealing that the Caturra Chiroso on Carmen’s farm—the source of Jhon’s trees—was likely an Ethiopian landrace:

The relevant section of the report produced by RD2 testing the Caturra Chiroso from Carmen’s farm, courtesy of Unblended

Unlike many Colombian coffee growers, Jhon doesn’t come from a legacy of coffee production; he began coffee production motivated by the opportunity to earn a better living specifically through the production of higher paying specialty coffee.

At first glance, the decision to plant just one type of coffee on his farm—an exotic cultivar, no less—might seem to be a curious or risky one. While highly productive and less prone to disease, like with Pink Bourbon and Gesha before it, Chiroso carries a reputation of instability of cup quality among coffee buyers. Cross-pollination increases this likelihood; but by ensuring the identity of his trees and planting them together, Jhon could protect cup quality and showcase the tree’s quality potential and, in theory, earn more for his coffee.

The Specialty Coffee Transaction Guide, which aggregates and analyzes anonymous data donated by roasters and importers in the specialty sector, supports the market reality of Jhon’s strategy. While global coffee prices in the specialty category (80+ cup score) rose in 2023, most of these gains tracked with the c-market; microlots and high-scoring lots, however, saw dramatically bigger gains:

By separating lots into smaller tranches of exceptionally high quality coffee, Jhon could earn more money—even more than if he produced larger lots or more coffee of lesser quality.

A study published in March of 2024 in World Development Perspectives validated this approach, examining the impact of quality and market access on incomes. Through market access with higher-paying international customers—also known as “direct trade”—and cultivation of higher-cupping and exotic cultivars like Gesha, producers in the study were able to make more money. While “commodity coffee producers commonly had to work on other farms for additional income” and even better-supported cooperative farmers “ maintained additional income sources to complement their earnings,” farmers that grew special and exotic cultivars like Gesha, Tabi, and Pink Bourbon, which also may have higher maintenance or tending requirements, “earned higher incomes and tended to rely exclusively on coffee farming.”

While the study showed economic benefits to growing specialty coffee—with specialty and direct trade relationship coffees earning twice the price of FNC coffees and exotic varieties earning 60-80% higher than average—it illustrated other benefits as well, including social/community benefits, ecological preservation, improved wages and permanent, full-time staff, and healthcare versus commercial coffee producers.

In his first year of production, Jhon produced just over 116kg of exportable green coffee; he sold all of it to Unblended at a price of $30,000 COP per carga. The same day, the price offered by the FNC—which doesn’t offer premiums for quality—was just $11,840 COP per carga.

Tags: chiroso colombia cultivars genetics pink bourbon smallholders

That's just, like, your opinion, man