Day 1 of the Copa de Oro competition in Huila, Colombia in November 2023 hosted by Osito Coffee

This piece is inspired by curiosities surrounding the process of sourcing Aviary’s release 003: Gildardo Lopez, as well as my history buying from the Cup of Excellence-winning producer of 004: Lino Rodriguez. Both of these coffees will be available for pre-order through the Aviary website. To place this piece in context of the coffees that inspired it or to support this blog and the work I do, please consider ordering them.

Over the last eighteen months, I’ve spent considerable time working with labs across companies and continents to bring ourselves into calibration with one another. I’m fascinated by the notion of calibration: the idea that one person could be trained to understand, interpret and evaluate their individual sensory experience in a way that perfectly aligns with and is understood by an entirely separate individual or group of individuals.

Calibration is the instrument that ostensibly gives power to certifications like the Q Arabica license—a license I held beginning in 2014 until I let the certification lapse—and is at the center of the global specialty coffee supply chain. In the world of sensory evaluation, calibration is shared reality; it enables us to speak the same language about quality and what we understand it to be.

If we believe that a coffee should be more valuable to a buyer and consumers based on its quality, then how we understand and speak about quality matters. After all, we buy coffee to taste and drink—not to look at—so how we perceive its flavor and aroma is part of its innate essence. Discordant understandings of quality arising from apparent lack of calibration—such as if an exporter or importer scores a coffee an 88 with an associated premium attached while a roaster scores it 86.5—can result from lab differences (roasting, extraction, cupping, culture) and lead to unnecessary risk, rejections and lower prices paid to coffee growers—as well as foster mutual distrust.

In the context of competitions like the Cup of Excellence, calibration can mean the difference between whether a coffee lands in first or second or third place—a determination that carries massive financial implications in the subsequent auction. Take for example the 2023 Colombia Cup of Excellence, where the spread between the first- and second-place winners was 0.22 points (90.61 vs 90.39 points). In the auction that followed, the second-place lot sold for $45 per pound, while the winning lot sold for $70.50—56% more. In the case of CoE Brazil’s experimental category the same year, the difference between second- and third-place might as well have been a rounding error: 0.03 points.

Cup of Excellence uses its own score system and score sheet, but jury members—all of whom hold extensive experience as cuppers—spend just a single day of cupping ahead of the competition to calibrate; the resulting calibration or lack thereof dictates the outcomes for the competition and its commensurate pricing premiums.

In November 2023, I flew to Garzón, Colombia to participate as a judge in the annual Copa de Oro competition held by Osito Coffee, one of my export partners in Colombia. The competition began first in the form of regional competitions—Copa Suaceña in Suaza, and Copa de Occidente in La Plata—where, like the Cup of Excellence before it had, Osito used the competitions as a tool both for quality discovery as well as buyer investment and connection. Through the event, Osito could solicit participation of specialty smallholders through the opportunity to win prize money and the promise of a guaranteed buyer for the current season with the potential for future purchases, and buyers would have access to some of the highest-quality coffees available through those channels.

When Osito’s competitions expanded to include coffees from Huila’s South, Central and West zones, Copa de Oro was born.

I’d wanted to participate in the competition since the inception of Copa de Occidente; at the time, I was the largest buyer of coffees from an informal collective of smallholders in La Plata organized under the banner of Grupo Mártir, many of whom participated in the competition. Copa de Occidente gave the growers recognition for the quality of coffees they produced, a premium for participating in the auction and the opportunity to win both prize money and the loyalty of price-insensitive specialty buyers. While I love 89-point coffees as much as the next buyer, it was more exciting for me to watch coffee producers connect with committed, loyal buyers whose companies were able to pay more for coffee than I could at the time—just as had happened after Lino Rodriguez, a smallholder in Palestina who I’d bought from and done processing work with in 2017, placed 13th in the Cup of Excellence the following year (a feat he would best in 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022 and 2023).

Finding buyers willing to pay for quality and understand the value of the coffee that they purchased is the utopian ideal of specialty coffee; meritocracy in a way that advantages quality-focused smallholders and gives them greater equity in the supply chain through participation in specialty markets.

[NB: there are, of course, many downsides and valid criticisms of the Cup of Excellence and similar competitions: gatekeeping, manipulation of entry requirements and harmful halo effects on pricing within local markets. This piece is not meant to be a broad promotion of these competitions, though I do believe they can, when executed properly and thoughtfully, be useful tools for opening access to better-paying and more competitive export markets for farmers particularly in areas that lack a perception of quality—the challenge facing Brazil that led to the first CoE]

I was unable to justify the travel to Colombia for the first Copa de Occidente, and the disruptions of Covid-19 the following year prevented my return to Colombia until this past November. I viewed the competition not only as an opportunity to re-engage and reconnect with the coffee growers I’d purchased coffee from for, at this point, seven years—but also as an opportunity to calibrate with experienced cuppers from some of the highest-regarded specialty roasters after three years of cupping remotely and in virtual isolation in my lab in Cleveland.

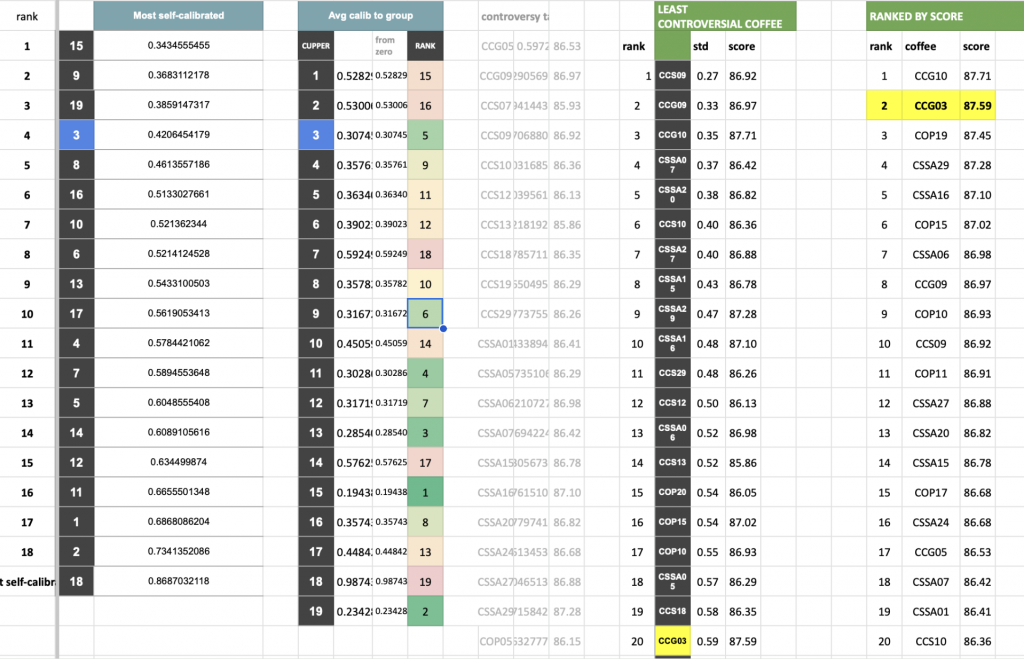

Following the competition and the crowning of its champion, Ivan Camilo Lopez (the son of the second-place winner and previous year’s champion, Gildardo Lopez Hoyos), I asked David Stallings from Osito if he’d be willing to share with me the blinded cupping results from the competition for analysis (both cuppers and coffees are blinded). I was specifically curious about the notion of calibration—within the group, within each cupper’s own scores, and within the group of coffees—and wondered what a statistical analysis of our scores might reveal. I haven’t taken a stats course since high school so I enlisted the help of the ever-generous astrophysicist-cum-coffee-physics-expert Jonathan Gagné to assist in getting me started with basic high-level statistics.

Before the competition, Osito’s Colombian team winnowed lots from 100+ smallholders to just thirty coffees for consideration in Copa de Oro. Nineteen cuppers participated as judges (with one judge leaving during the final round due to illness), calibrating one day ahead of the competition using coffees known to and pre-selected by Osito. Coffees were roasted the day before cupping using a Roest and then cupped over three rounds. For the first two rounds, coffees were separated by region, with the third and final round bringing them all together on one table. Scoring was done using the SCA score sheet; from the group of cuppers, for each coffee, the outlier scores (both high and low) were discarded, the remaining scores were averaged, and the highest-scoring coffees advanced through to each subsequent round.

If our panel of cuppers was out of calibration, it would have implications for the the participants of the competition: the winner received a price of $8.5mm COP/carga (a price roughly 600% higher than the FNC daily price) for their winning lot and the first-place winners from the other regions received a price of $7mm COP/carga; the second-place winner (Gildardo) received a price of $6.5mm COP/carga, third received $6mm, fourth $5.5mm, and fifth $5mm. All of the rest of the participants in the top 30 received a premium over normal prices at a price of $2.1mm COP/carga.

In other words: depending how well calibrated we were as a group and depending on the noise extant within that calibration could impact just how high the price a producer received was.

[The data is here for those who are curious or would like to make visualizations from this data; I’ll add them to this post later]

I’d been curious to see if there was some effect of “gaming” scores happening—if a cupper really liked a coffee and wanted to see it advance to the next round (over another on the table) they might try to inflate the score for that coffee higher than they might naturally grade it while still attempting to avoid being the outlier. We’d run the stats to demonstrate ‘self-calibration’—in other words, how consistently a judge scored a coffee for each of its three appearances through the competition—and I speculate that the idea of ‘promoting’ a coffee through score inflation could likely be detected by that cupper having a bigger standard deviation, but only for the coffees they scored highest (we did not run this analysis—yet).

I was also curious to know if there were cuppers who were most calibrated with the group as a whole (since in theory we are trained to make determinations about quality that the broadest population of people will mostly agree agree with) as well as who were least calibrated with the group as a whole; I was curious which coffees were the most controversial (highest STD of scores) and least controversial. I also wanted to know how scores drifted between rounds—which could be a result of roasting effects (since coffees were re-roasted each time before they were presented on a new table), cupping context (where on the table it was, or which coffees it was with), promotion/score gaming, or lack of self-calibration within even just a few cuppers.

All in all, we were fairly well calibrated as a group; the standard deviation of our scores was around 0.70 through the competition, meaning that about 68% of the time, our spread of scores was 0.70 points or less. This is well within the acceptable range of calibration—on the Q we aim for +/- 0.50 or a spread of 1 whole point.

Cupper 15 was the most well-calibrated with themself, achieving a standard deviation of 0.343 for their scores; the least self-calibrated cupper, on the other hand, was Cupper 18 with a standard deviation of 0.869 points. This means that if a coffee were presented three times on three tables they might score it anywhere from 85.25 to 87. This placed them out of calibration with the group as a whole, with their score being an mean of 0.97 points away from the average, calibrated group score for each coffee. This is an interesting test; while it might make sense that a cupper who is self-calibrated and consistent might also be well-calibrated with the group (and indeed Cupper 15 was the most calibrated to the group, with a difference of 0.317 points on average from the group’s calibrated mean score), it’s not always the case: Cupper 11 had the 16th-lowest score for self-calibration (STD of 0.666) but was 4th out of 19 for group calibration. Similarly, Cupper 8 was 5th-most calibrated with themselves yet 10th in terms of group calibration. I believe this suggests that while they are perhaps not a consistent cupper, they have biases or preferences that consistently diverge from the preferences of the group at large. This one case exemplifies how cultural bias or preference could play out in a real-world context; if a cupper finds certain qualities to be desirable in a coffee, like savory-funk for example, and consistently scores those coffees high, they might find themselves consistently out of calibration with the group and yet not technically incorrect. This is the subjective part of coffee which, in my estimation, is difficult to calibrate around since so much of preference relates to our lived experiences.

I averaged the scores (less the highest- and lowest- scores for each coffee, per the competition rules) for each coffee for each appearance it made during the competition and calculated the “drift” in average scores between rounds. Of the 30 coffees scored at least twice, scores decreased for 16 of them between rounds 1 and 2 and increased for 14 of them; meanwhile, for the 14 coffees that appeared in the final round, just four experienced a decrease in average score in the third round of cupping, with one scoring exactly the same and 8 seeing score increases that ranged from a delta of 0.03 to 1.19 points. Context, it would seem, matters tremendously: since the coffees were contextualized with the best of the best, it highlighted both positive and negative contrasts, exacerbating any apparent differences in quality between coffees (all of which were agreed by the group to be the best coffees in the competition).

Overall, however, the score drift average per round was just +/- 0.12 points, meaning that we were, as a group, fairly consistent with each appearance of a coffee—but when defining drift as”looking at the average of “distance from group average score” (in other words the absolute value of drift) the amount of drift between rounds increases to 0.36 points.

Strikingly, 0.12 points is the same as the difference in average score between the first-place, winning coffee (87.71 points) and the second-place runner-up (87.59 points). This 0.12 points difference could be explained by score drift; it could be explained by context or roast; it could be explained by noise or the system of score calculation; or, of course, it could be explained by differences in quality.

But that differential—just 0.12 points, just noise in the system—meant a difference in price of 2 million pesos per carga to the producer.

That second-place lot was the one I purchased to offer through Aviary (decoding it was an easy feat since I knew the coffee’s final score as well as the overall placement of the lot). It was, relative to other coffees in the competition, a fairly controversial coffee: out of the 30 coffees in the Copa de Oro competition, the scores for it had the twentieth-highest standard deviation (0.59). The highest-scoring and winning coffee in the competition, however, was among the least controversial (3rd out of 30) with a standard deviation of 0.35 points. This suggests that while the difference between the two coffees is minute, and while some cuppers indeed preferred the second-place lot (myself included), we nearly universally agreed that the quality of the winning lot was excellent. I believe that even in a ranked-choice system of election that the winning coffee—another Pink Bourbon—would have and should have won.

Because I kept my notes from the competition, I was able to determine how well I did as a cupper in maintaining calibration—a piece of feedback I found invaluable and informative since I work professionally as a buyer. Overall, as a cupper I was the fourth-most calibrated with myself in the group (with a standard deviation of 0.421) and was the fifth most-calibrated cupper with the group at large (with a delta of just 0.307 points, on average, from the group’s calibrated mean scores). I find this intriguing; it means that overall, I am indeed well-calibrated with a large group of trained cuppers, but also that depending on its roast or context I might score the same coffee anywhere from 86.5 to 87.5—depending on the day, depending on the roast, depending on any number of factors.

We like to view ourselves as infallible arbiters of quality—and as a buyer, how we score coffees impacts whether or not a coffee is rejected on pre-shipment or arrival, as well as how much the producer is ultimately paid. What the data from the Copa de Oro sessions shows, however, reveals a more striking truth: even when calibrated, we are individually unreliable at determining quality in a consistent manner.

That variations in day, context and presentation can cause variations in scoring that impact a coffee’s economic value or marketability is something that should give us pause; it renders scoring as an “objective” metric of quality questionable at best. Scoring should understood to be a fluid metric—one with a margin of error, and one that moves and shifts and drifts and changes. The more tasters we have on a panel, the more those cuppers are in alignment, and the more consistently those cuppers regard a coffee through multiple appearances, the stronger our confidence should be in that coffee’s evaluation. But without knowing how “controversial” each coffee is, or how calibrated cuppers are to themselves or each other, it’s difficult to have confidence—particularly since most companies, be they importers or roasters, typically only have one or two spoons dipping into each coffee they consider.

Tags: aviary calibration competitions cupping scoring

Useful

Interesting stuff!

Is there any evidence in the data of individual cuppers being generally looser or tighter in terms of the range of scores they are willing to give?

This is a tendency I’ve noticed in people I cup with – that some will tend to (I assume subconsciously) exaggerate small differences in quality to distinguish coffees from each other, while others tend to be reticent to give markedly high or low scores, perhaps for fear of being wrong.

I’m curious how good a job formal cupping training does at eliminating that tendency in people.

There is certainly this tendency — calibration cuppings ahead of competition scoring with time allotted for discussion helps with some of this, as does training.

There’s a continuum of scale that varies between datasets. Wall Street quants (and radio astronomers) deal with minute variations, but they have bajillions of observations so they can detect statistical differences at the 0.0000001 level. I used to do research on countries’ institutions where I’d be lucky to get a few hundred observations and came away with the impression that that domain of knowledge is, more often than economists want to admit, better dealt with as history than statistics. But the rule of thumb I was taught is that you need at least 30 observations to bother messing with a linear regression. For something simpler and less strategic than a country’s court system that’s reasonable enough.

An individual contest with 20 judges evaluating coffee is that much harder to quantify. It would be awesome if someone put together a central repository for this sort of data in a way that would allow more elaborate models and visualizations to identify, e.g. niche preferences and the cuppers who have them.