The sourcing work behind Aviary’s 2025 season was inspired by this inquiry; the research and work required to publish this piece was made possible through the support of Aviary 2025 season reservation holders.

UPDATE (2025-01-07): This piece now includes comments submitted by Dr. Montagnon of RD2 Vision at the end.

The incursion began at two o’clock in the morning as the town slept. The eighty rebels obscured their identities with ski masks and the darkness of night as they entered the agricultural cooperative of El Porvenir, 45 kilometers outside of Tingo Maria.

A month earlier, cooperative members reported that unknown individuals had approached them in the nearby town of Rio Azul, inquiring about the identities of the cooperative’s leaders and demanding payment of 30 million soles to ensure the safety of the cooperative and its members. The cooperative, dismissing the seriousness of the threat, declined to pay; a week later, 2,500 square meters of tea plantings were burned.

By the early 1980s, Sendero Luminoso (SL, or “The Shining Path”) had built enough support to expand its activities through the Andean highlands toward Tingo Maria, aligning themselves with coca farmers and making Tingo Maria a hub for its activities in the narco trade. The insurgency’s increasing use of violence—reprisal killings of indigenous people, assassination of police and local officials, and sabotage of infrastructure—intimidated government officials into resigning; those who remained in office responded with complicity or ambivalence. This, combined with early populist rhetoric targeting the government for widespread perceived neglect of the rural, agrarian communities, allowed the Shining Path to continue to gain influence, credibility and support, enabling the scope and brutality of their operations to grow. In August 1984, the New York Times reported that “Since last October, when the guerillas first appeared in the area, the police estimate they have recruited 1,500 to 2,000 people in the valley.”

In the early days of the movement, the rebels would have armed themselves with knives and machetes ahead of their raids, splitting into contingents when they arrived at their destination, one to stop traffic, one to steal supplies in town, and one to rob the closest police precinct in the hope of collecting armament they could use in their attack. After looting the armory, they’d leave the station in flames, bombing it using “quesos rusos”—improvised plastic explosives: The news reported that “Operating in bands of up to 100 young men and women, they have dynamited 10 of the 13 police stations in the region, attacked banks and killed 19 policemen.”

But by February 13, 1986, there was no need for the detour: the rebels fanned out through El Porvenir armed with rifles, revolvers and machine guns, waking the 5,000 members and their families at gunpoint to force them outside their homes and then set them ablaze. With the cooperative watching, the Sendero Luminoso militants finished their task: they stormed the administrative offices of the cooperative, burning accounting documents, destroying furniture and equipment used for hulling and cleaning coffee—and then, with the cooperative in cinders, some seven hours after the attack began, they burned the coffee fields.

Sections

Introduction

Timeline of key events in Peru

A stranger in a strange land

A brief history of Peruvian coffee

Inca Gesha, or should we say SL-9?

The founding of the Experimental Station at Tingo Maria

Scott Labs Selection 9

The FAO mission to Ethiopia

Destruction of the agricultural research station

Accessions in Peru

A theory of lost origins

Inca Gesha

Key developments:

Mid 1700s: Coffee is brought to Peru by Jesuit missionaries

1869, 1880: Rust epidemics decimate coffee production in Sri Lanka, Java

1886: Peru signs the Grace Contract, leading to large-scale planting of coffee by the British

1903: Scott Agricultural Laboratories is founded in Kenya

1910: Synthetic fertilizer is introduced

1920s: British withdraw business interests from Peru

1933: Beginning of Scott Labs variety improvement trials

1936: Carretera Numero 2 completed, connecting the Huallaga River Valley to the Pacific Coast

1941: The U.S. enters WWII; Peru severs diplomatic relations with Japan

1942: Peruvian government program of land expropriation of Japanese interests

1946: Founding of the Tingo Maria Agricultural Experiment Station

1964: FAO mission to Ethiopia

1968: Coup d’etat by General Juan Velasco; agrarian land reforms

1969: Sendero Luminoso founded

1980: First elections in Peru since 1968; SL begins “people’s war”

1988: SL destroy experimental station

~2015: Seeds from Hacienda Esmeralda begin distributed in small network around Peru

Nearly everywhere it grows, coffee is a stranger in a strange land. Native only to Ethiopia (and as we know now, South Sudan), much of the history of the transmission of Coffea arabica around the world exists only in lore and legend, unsubstantiated by evidence; much has been lost or left unreported or undocumented; much has otherwise been forgotten.

Commercial coffee cultivation came first to Yemen in the 16th century using seeds transported out of Ethiopia. For nearly two centuries, Yemen—shipping out of its now-infamous port of Mokha—was the world’s sole supplier of coffee. Protecting its trade interests, green coffee would be partially roasted to kill the embryo before export so as to prevent coffee from being germinated for planting elsewhere, which would undermine the country’s monopoly.

And yet, it happened: today, much of the production in the world can be traced to lineages originating in Yemen, including Bourbon and Typica; as a result of this bottleneck, there is less genetic diversity in coffee than in nearly any other cash crop on earth.

Tales of deception, subterfuge and intrigue are central to the mythology behind coffee’s dissemination: seeds smuggled by Baba Budan from Yemen to India in the 17th century; or cuttings smuggled by Peter van der Boecke to Amsterdam in 1616 which went on to Indonesia; or French Naval Captain Gabriel De Clieu, who, according to legend, in 1723 seduced the daughter of the head of the Jardin Royal des Plantes to steal a cutting, smuggling it to the island of Martinique; or Imam Al-Mahdi of Yemen gifting 60 seedlings to the French that would go on to be planted on the Island of Bourbon—though Yemen prohibited the export of viable seeds to protect their monopoly—reportedly due to the Imam’s relationship with a French agent, Imbert, who had, according to the Imam, relieved his distress resulting from an ear abscess.

Even in the modern era, I’ve heard similar tales—of bolt cutters and ski masks and seedlings being taken, seeds stolen in the night. One story goes that Sidra and Mejorado came from an abandoned Nestle farm in Ecuador—and in Guatemala, “Bourbon Chocolá” was taken from Finca Chocolá before the plantation was converted to production of corn.

But the rediscovery of Gesha at a farm in Panama and the subsequent gold rush at auction set in motion the modern era of specialty coffee; a tree out of Ethiopia, rather than descended from one from Yemen. I’ve long been fascinated by these stories—as well as the potential qualities or cup impacts that result from different cultivars. I’ve mused about a few: Castillo and Caturra, Ruiru 11 and Batian, and Pink Bourbon and Chiroso.

And, of course, I have my favorites—one of them being a cultivar known as “Inca Gesha,” that grows in the highlands along the Andes in Peru.

In the spring of 2024, I began a deep-dive into the history of Peru and its coffee industry as part of my research process toward developing a sourcing strategy for an import that never, as it turns out, happened. I thumbed through The Peru Reader and The Corner of the Living, trying to make sense of and understand the deep complexities of a country whose civilized history spans 15,000 years and which was not only home to the earliest known civilization in the Americas but the seat of power for the Inca Empire.

Coffee didn’t arrive to Peru until the 18th century during the period of Spanish colonization, brought by Jesuit missionaries—as in Colombia and Guatemala—as an ornamental tree and only used for personal consumption. Until the late 19th century, Peru’s primary export was guano—a word derived from the Quechua word for bird excrement, which, for millennia, they’d used as a soil amendment. Small islands offshore of the country’s long desert coastline accumulated guano; after nationalizing the industry in the 1840s, exports of guano became the state’s largest source of revenue generating wealth for the country that not only enabled the abolition of slavery but also the head tax on Indigenous peoples. [As a fascinating aside, this export of guano may have directly led to the potato blight and subsequent famine in Ireland which precipitated mass migration to the Americas].

Peru’s loss in the War of the Pacific resulted in the country ceding half of its guano income to Chile; after defaulting on a note to the British government borrowed for its expenses in that war as well as its war of independence against Spain, in 1886, Peru signed the Grace Contract to retire the debt owed to Britain. In exchange, Britain received mining rights, control of Peru’s railway for 66 years and 1.8 million hectares of the Andean highlands.

When coffee leaf rust, Hemileia vastatrix, decimated coffee production in Sri Lanka in 1869 and then in Java in the 1880s, Peru—and its fertile soils, high Andean slopes and ideal climate—emerged as an alternative for European investors, and nearly a quarter of the land transferred to the British was developed for agricultural purposes for export to Europe, including the large-scale planting of coffee in 1887.

The advent of synthetic fertilizers produced using Fritz Haber’s catalytic process collapsed the guano industry beginning in 1910, leaving coffee as a viable export alternative. By the beginning of World War I, coffee accounted for 60% of Peru’s exports. Two World Wars, a global depression and the decline of its empire led the British to withdraw their business interests from Peru beginning in the 1920s. Indigenous peoples who lived in the highlands above the plantations and who provided the labor for the farms took over use of the land or purchased it from the departing British interests, becoming smallholder coffee growers.

In that context, the Peruvian government’s 1960s policies of Agrarian Reform continued this process, reorganizing land use by transferring land from large estate holders to indigenous peoples and campesinos and organizing smallholders into cooperatives. These state-supported cooperatives would go on to produce over 80% of the coffee exported from Peru under the quota system established by the International Coffee Agreement. With a guaranteed buyer and without incentive to improve their quality or operations, the cooperative system suffered from corruption and nepotism; after the ICA collapsed in 1989 sending prices below $1 and Alberto Fujimori imposed neoliberal policies gutting regulations and dissolving the Agrarian Bank, exports collapsed and export routes fell apart.

From this economic insecurity and neglect of the campesinos and rural countryside emerged Sendero Luminoso. Their violence—and the government’s retribution—led the population to flee to urban centers, further deteriorating trade routes, agricultural support services, credit, and agricultural production. Without strong export systems and without national support, many farmers—encouraged by the overtures of Sendero Luminoso—abandoned coffee and turned to the production of coca.

My phone vibrated with a text message from Lance Schnorenberg of Sey.

I’d been in Brooklyn a few months before and stopped by the café in Bushwick. Lance and I caught up. I told him about my ongoing research and prospective travel to Peru, hoping we could coordinate a time to cup together in Lima or Jaen. I mentioned that I was fascinated by the number and diversity of Geshas I’d been seeing and tasting from Peru—as I hadn’t seen or heard of any real explanation of how they got there.

“I don’t think it’s Gesha.” Lance told me, lowering himself to sit beside me on the floor of the shop. I listened as I sipped through three different cups of coffee. “It just doesn’t always seem to taste or look like it. I think,” he paused, “there might be a lot of introgressed Gesha out there that people are calling ‘Inca Gesha.’ We sent leaf samples to Christophe for testing. I’ll send you the results when we get the report.”

There were other theories. Tim Hill, formerly the buyer of Counter Culture Coffee and now with Atlantic Specialty Coffee, told me he believed that what we called “Inca Gesha” was simply actual Gesha seeds being planted across Peru. This did make some sense: I knew of at least one case where a grower had collected Gesha seeds off the Esmeralda table at an expo, brought them back to Lima, sprouted them and distributed those seedlings to friends. I’d bought other coffees that were from certified Gesha seeds originally from Panama or Costa Rica, but in either case, those plantings didn’t happen until less than a decade ago and don’t cover the broad and storied presence of “Inca Gesha” I’d seen across various regions—nor did it explain the fact that buyers have been talking about the Ethiopian-like profiles coming out of Peru for longer.

Before genetic fingerprinting and modern techniques, the identification of different trees was often based on appearance or morphology, or storytelling rooted in a farm or farmer that first found the tree, or based on variants of the traditional trees in the area. But rarely do the stories we tell have any connection with a cultivar’s actual provenance: Pink Bourbon was called Pink Bourbon because it grew on a farm with Red and Yellow Bourbon and was believed to be a hybrid of the two; Chiroso was believed to be a mutation of Caturra because it grew on a farm planted with Caturra; both, as it turns out, are Ethiopian landraces.

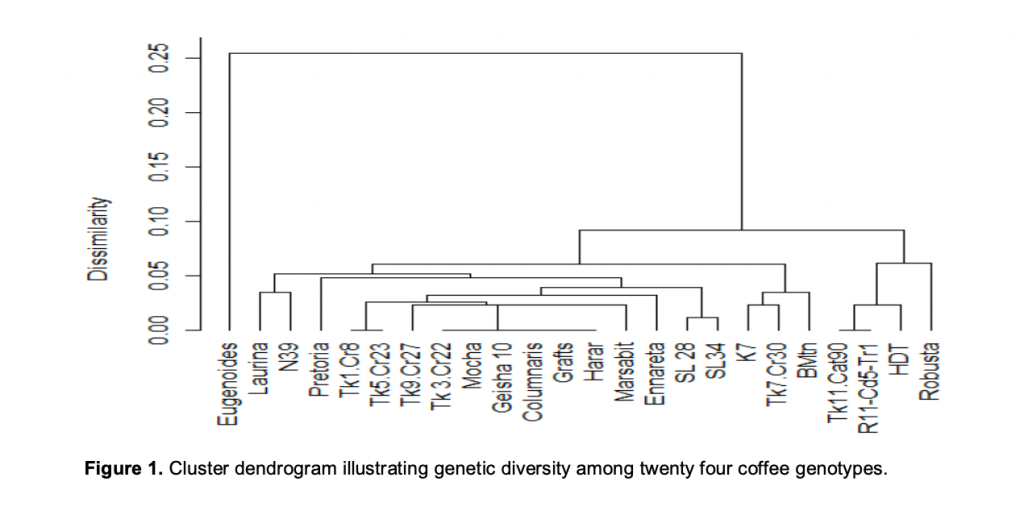

Today, we have technologies available that enable us to, relatively affordably and with a high degree of confidence and precision, identify the genetic relatives of an unknown coffee tree. The most well-known independent lab, RD2 Vision, is operated by Dr. Christophe Montagnon, whose studies and journal articles I’ve referenced countless times. To identify a coffee, Dr. Montagnon compares a sample submitted against RD2 Vision’s database of known exemplars built by collecting the genetic fingerprint from the CATIE collection housed in Costa Rica and other ex situ collections around the world.

Counter Culture’s work with World Coffee Research—where, as with CIRAD before it, Dr. Montagnon worked prior to founding RD2 Vision—ushered in a new wave of curiosity among roasters and importers to establish or verify the genetics of the coffees they purchased. It was through this line of inquiry that Aida Batlle, whose farm Finca Kilimanjaro produced coffee that Counter Culture had bought for a decade, learned that rather than growing Bourbon, the trees on her farm were more closely related to SL28 and SL34. This served to partially explain why the quality from that farm was so much higher than other farms in the area—even those with similar practices.

By submitting seeds or two young leaves from a tree in a paper envelope and paying an invoice, a producer or roaster can learn if the tree that seems to yield more, have higher resistance to roya, or cup better than its neighbors is actually what the nursery told them—say a Bourbon, or a Caturra, or a Typica—or if it’s something else entirely. The method of analysis used by RD2 in its analysis, 11-SSR Fingerprinting, is the gold-standard for reproducible, high-resolution methods of testing, forensic in accuracy and utility. It can, with a high degree of confidence, answer the question: “Is this tree Gesha—and if not, what is it?”

Leaves, of course offer a more reliable marker. While typically thought of as self-pollinating, cross-pollination in Arabica can and does occur. This means that even if an “Inca Gesha” tree were, in fact, a Gesha, it could produce fruit that was the result of cross-pollination with other non-Gesha trees and thus taste and test as introgressed—even if it weren’t.

I opened the text message from Lance. He’d attached the report from RD2, who’d examined the leaves that Lance had collected from a tree the farmer called “Inca Gesha.” I scrolled to the section labeled “Analysis and interpretation” on the sixth page.

Lance’s suspicions appeared to be warranted:

This sample is corresponding to a very rare cultivar. I have not seen this very fingerprint in my database before. It is belonging to the “Ethiopian Legacy” group. Known cultivars of this genetic group are SL-34, K-7 and Mibirizi for instance, but also SL-09. It is actually very close to SL-09, and it might well be it as we can accept slight genetic difference from ancient, not necessarily well identified references. In East Africa today, from all the selected SLs in the 30’s, SL28 and SL34 are the most widely grown cultivars. SL-09 is not widely cultivated. It is said to be very susceptible to Coffee Berry Disease (Ojo, no es la broca = Coffee Berry Borer) which is endemic to East Africa, but absent in the Americas. It is not an Ethiopian landrace and hence It is not even close to Geisha.

The results surprised me. Not that it wasn’t Gesha, but: I knew of two different cultivars commonly referred to as SL-09; neither, to my knowledge, had ever been transported to Peru. And one of them—the one identified by the report—had never been distributed for commercial cultivation.

And yet: the genetic fingerprint showed that Inca Gesha was “very close” to and “might well be” SL-09—a fact that, once revealed, resulted in these coffees being marketed as SL-09 by exporters, importers and roasters.

For months, I obsessed over this revelation: How could Inca Gesha be SL-09, when the history didn’t add up? And if it is SL-09, how did it get there?

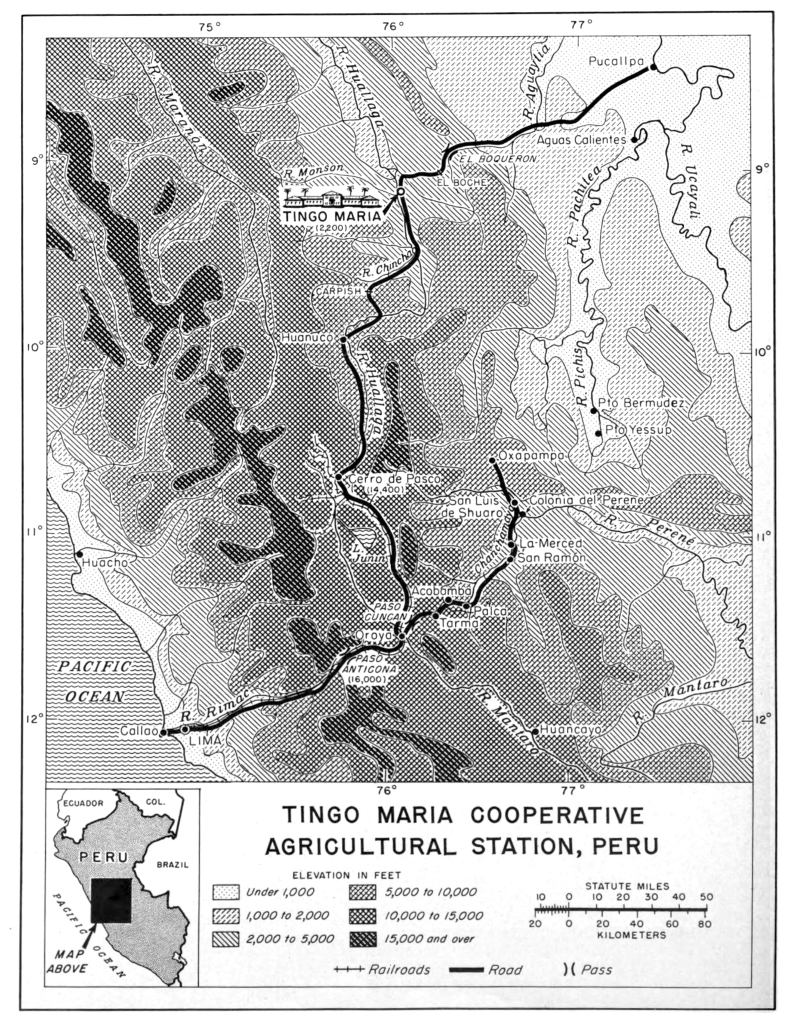

Until 1936, when road construction hollowed out the jungle to connect the Huallaga River valley region to the Pacific coast, Tingo Maria was virtually unreachable and uninhabited. 17th century Jesuit missionaries, after hearing from indigenous peoples about a large city rich in gold called Paititi, believed that the impenetrable jungles on the eastern slope of the Andes concealed the lost city of El Dorado. That city was never found—but in its stead, after the completion of a 424-kilometer highway, Carretera Numero 2, between Huanuco and Pucallpa, the hamlet of Tingo Maria grew.

After Peru’s president, Manuel Prado, yielded to political and economic pressure from the United States following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, he severed relations with Japan in 1941 and in 1942 imposed a program of land confiscation—expropriating land from Japanese in Peru and deporting them to internment camps in the U.S. This expanded the government’s power to expropriate land for road development—granted under the 1938 Law 8621—which permitted the state to expropriate uncultivated mountain lands running alongside both current and planned highways. One of the areas expropriated along the Tulumayo river was Christened by the Peruvian government as Peru’s “Official Colonization Zone” in an effort to entice landless peasants living in the Andes to settle the area and put it to agricultural use. This agricultural colonization program brought settlers to the Huánuco Region leading to rapid growth around Tingo Maria and conversion of land into agricultural use.

Meanwhile, embroiled in theaters of war across Europe, Asia and Africa, the U.S. government sought new sources for raw materials necessary for its war efforts, leading to the establishment of new Tropical Research Stations across the world. On April 21, 1942, the United States Department of Agriculture entered into a contract with Peru’s Division of Colonization and Forestry for assistance with a project: The Tingo Maria Agricultural Station. The New York Times in 1943 reported that “The United States, through the Department of Agriculture, in cooperation with the State Department is contributing financial and technical aid, while Peru is contributing land, buildings and other facilities.”

The Estacion Experimental Agricola was “one of a series of agricultural experiment stations being established throughout the American tropics designed to assist and encourage the production on a large scale of rubber, quinine and other products formerly obtained from the Far East.” In the early years of the agricultural experiment station near Tingo Maria, it was run by scientists from the U.S. Department of Agriculture—the first, in 1943, was Dr. Benjamin J. Birdsall—in cooperation with the director of forest lands and colonization. In its first decade, a total of 23 American scientists served at the station, typically with five on duty at a time and a goal of “working themselves out of the job” by “training Peruvians to take their places.”

Together, the Americans and their Peruvian counterparts “worked on problems of crops in the Peruvian jungle lands lying east of the Andes and at the headwaters of the Amazon River. These are crops important not only to the Peruvian economy but also to the United States market.” With U.S. backing and support, the station became “the hemisphere’s premier tropical extension station.” At the station, under experimentation were “coffee, pasture or forage grasses, bananas, rubber, cacao, citrus, forestry products, oil palms, tea, rice, corn and several other products. A dairy herd is also maintained, and work is being carried on with pigs, rabbits and poultry.”

In 1946, the Tingo María Colonization Zone was established; by 1960, over 40,000 acres were planted with crops—chiefly among them, coffee:

The settlers have generally established their coffee in the forests after cleaning only the underbrush. This method which may give satisfactory results in areas where the upper story of trees is constituted by species suitable to shading is detrimental to the production where these species by their shape or development cannot be controlled to form the kind of canopy suited to the crop. Such a system is of the most extensive type, the coffee being grown almost like a forest tree. In very steep land this method of exploitation has however the advantage of being almost ideal from the point of view of soil conservation.

In the 1950s, plantings of the crop expanded, reaching 5,000 hectares in 1962, according to the report “Coffee Activity in Tingo Maria” from the SIPA Socio-Agroeconomic Studies Office.

The Experimental Station, which covered 225 hectares, played a critical role in agricultural research as the industry around it and the number of cooperatives it supported grew—cooperatives that included Pucate, Arequipa, Piura, Central de Cooperativas de Aucayacu, Agraria Naranjillo and El Porvenir. Reports from the early years show that the studies carried out by the researchers at the station examined productivity, disease resistance, investigations of crop improvement, and, notably: variety trials. In these trials, cultivars from other places were planted in fields around the station to observe their traits and behaviors. A status report published in 1958 provided a summary of the stations plans to “undertake variety trials in six different localities, including the Tingo Maria Experiment Station. Seeds of coffee varieties and further information on this test were sent upon request.”

Some of the initial cultivars planted around Tingo Maria are recognizable by their modern-day names; others are less commonly used today or less well-known. Each type would be planted both in shade and full sun both near Tingo Maria as well as surrounding areas of Tulumayo, Tingo Maria Tea Garden, Convencion, Satipo, Chanchamayo, Tarapoto and Moyobamba with a trial duration of 10 years According to a 1957 report from the Inter-American Institute of Agricultural Sciences, the initial plan for variety improvement trials included: Local, Columnaris, Mundo Novo, Caturra Rojo, Sumatra, Bourbon Salvadoreño, Bourbon Amarillo, Villalobos and Villasarchi.

Notably absent from this list: Gesha, or any other apparently Ethiopian-type coffee.

But: another 1957 report from the International Cooperation Administration later made available by the Office of Public Records, “Technical Cooperation Through American Universities,” noted that alongside the Tingo Maria station’s exploration of Ethiopian varieties of corn (which “did better under improved methods of cultivation”), and cross-breeding of Ethiopian cattle (which “has shown very great possibilities”), “much attention has been given to coffee cultivation—one well-known variety is native to Ethiopia and coffee is already an important export.”

And, Volume 14 of Economic Botany from 1958 notes that “In the past six or seven years Ethiopian coffees have been systematically introduced in the Western Hemisphere.” The 14 varieties collected in 1951 by the Agricultural Explorer of the Section of Plant Introduction of the USDA were forwarded to “several Stations south of the Rio Grand.”

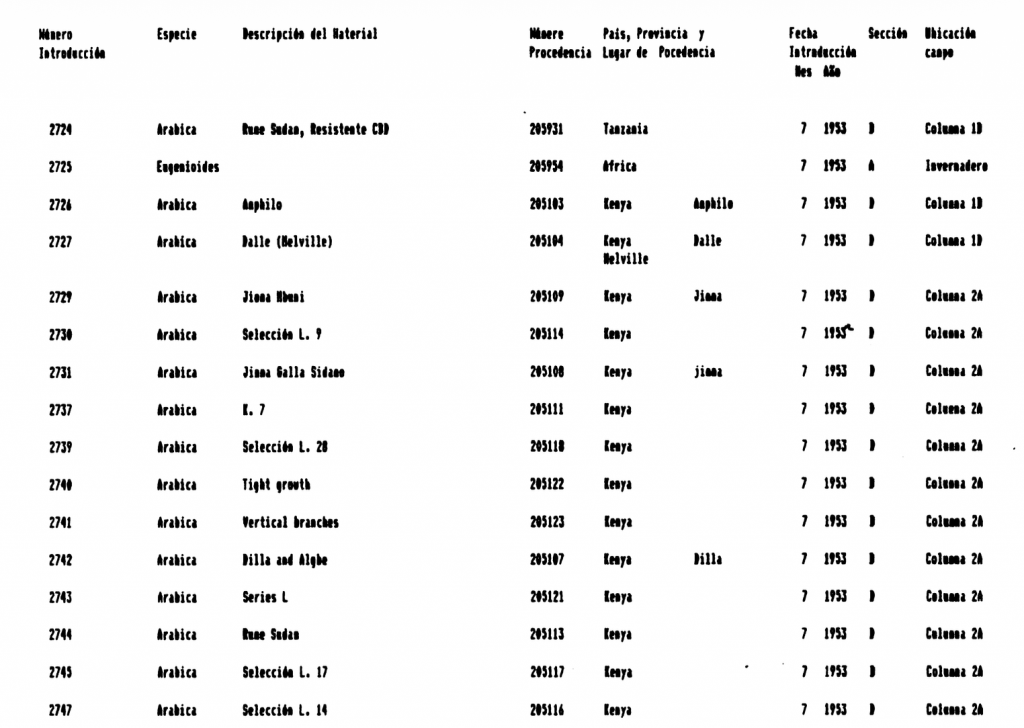

An entry numbered 2730 in the CATIE repository recorded that in 1953—prior to the introduction of materials from the FAO mission to Ethiopia—the institute received germplasm from Kenya that was designated “Selection L. 9” or “S.L. 9.”

Founded in 1903 by the Kenya Colonial Administration under British rule, Scott Agricultural Laboratories in Kenya played a central role in growing the coffee sector in Kenya. As part of its work, Scott Labs, like other tropical research stations, implemented a variety improvement program—from which SL-9 emerged.

While the origins of its better-known and widely-cultivated peers SL-28 and SL-34 are fairly well established—SL-28 being a 1935 selection from Tanganyika Drought Resistant trees planted at Scott Laboratories (originally collected in Tanzania) and SL-34 coming from a single-tree selection from the Loresho Estate planted by the founder of the infamous Happy Valley set ostensibly from “French Mission Bourbon” seeds—SL-9 was, according to a piece written by P.A. Jones, the Agricultural Officer of the Coffee Research Station, in a 1956 bulletin from the Coffee Board of Kenya, “from a block of unknown origin.”

Like India, which created the other cultivar sometimes referred to as SL-09 (though better and more accurately known as “Selection 9”), Kenya held collections of germplasm from Ethiopia—from a 1929 introduction through the British Consul in Harar; from a 1936 selection collected by the British Consulate in the Gesha and Amfillo districts some claimed to have been resistant to coffee berry disease; and from a collection of specimens named “Dalle, Dalle-Mixed, Dilla, Dilla and Alghe, Gimma Mbuni, and Gimma Galla Sidamo” gathered by three coffee-curious army officers during an Ethiopian campaign in 1941-1942 (the Scott Labs selections later known as SLs, though, occurred between 1935 and 1939, which excludes germplasm from the later campaign).

In addition to Ethiopian varieties, Scott Labs also held material from other sources which would prove integral to the Scott Labs variety trials: French Mission, a heterogenous type coming from three different introductions beginning 1893 from Yemen, Bourbon and a type similar to those grown in Central America; Mokka, introduced in 1934 from Puerto Rico but originally from Java; Kents, an F5 introduced in 1930 descended from a selection by L. P. Kent in 1911 of a single tree growing on his Doddengoodda Estate in Mysore; Mysore, a heterogenous type resistant to Coffee Berry Disease imported in 1908 from Southern India; Blue Mountain, introduced in 1913 from the Blue Mountains of Jamaica, where it had been established in 1730 from progeny in Martinique from a single plant at the Botanic Garden in Amsterdam taken in 1723; Guatemala, whose features were similar to Blue Mountain; San Ramon, a dwarf from Central America; Padang, introduced from Puerto Rico, “whence it had been introduced from the Botanic Gardens, Buitenzorg, Java, in 1908”; Columnaris, which was introduced from Puerto Rico around 1931 but originally came from the Pantjoer estate in Java; and Maragogipe from Bahia, Brazil. Other types later added included Rumé Sudan and Barbuk Sudan.

Scott Labs contained blocks grown from its germplasm collection to explore specific traits of each of the selections such as drought resistance. Drought Resistant I (D.R. 1) and Drought Resistant II (D.R. II) blocks were established in 1933 in Kabete from unknown origins of its collection (but likely derived from the French Mission selections); both had broad leaves and bronze tips (D.R. I being light bronze, D.R. II being dark bronze); Tanganyika Drought Resistant was selected from a bronze-tipped somewhat disease-resistant variety in 1931 from Rasha Rasha in Tanzania that appeared similar to Bourbon but produced lower yields but a high percentage of elephant beans of exceptional quality.

From these blocks, all of the “SL” designated cultivars originated, derived as single-tree selections—including SL-09. According to the 1956 bulletin:

…some 42 trees of various origins were selected and studied for yield, quality, and general features, such as drought and disease resistance. Many were discarded after a year or two, others survived and were subsequently discarded. The fifteen which are described here were continued long enough to be included in variety trials and some of these have proved sufficiently valuable to merit their distribution for commercial use.

Because of its lack of resistance to rust and its susceptibility to coffee berry disease, the variety was never distributed. In other words: as far as any historical evidence shows, SL-09 was never—unlike SL-34 and SL-28—commercially grown outside of Kenya (I did find evidence of a variety trial in Malawi where SL-09 was planted alongside its more-famous peers).

Therefore, even if it genetically seems to be closely related to SL-09, Inca Gesha can’t be SL-09, unless: perhaps—by some coincidence—the tree that would be selected to create SL-09 was the same type of tree that appeared in Peru decades later.

In 1964, five scientists representing the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations joined five observers from Ethiopia on a mission to Ethiopia “to gather botanical, entomological, genetical, and horticultural data for the increase of knowledge and understanding of the Arabica coffee plant.” The mission’s team included L.M. Fernie, a plant breeder representing Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda; D.J. Greathead, an entomologist representing Uganda; L.C. Monaco, a geneticist from Brazil; R.L. Narasimhaswamy, a breeder from India; and the mission’s leader, Frederick G. Meyer, a botanist representing the United States.

Between October 15, 1964 and January 15, 1965, the team traveled through Ethiopia’s primary growing regions from North-to-South, collecting data about the varieties being grown including productivity, height and branching tendency and diseases present. They collected data related to apparent susceptibility of coffee leaf rust, other pathogens, and pests according to each of their specialties, documenting their findings in a report presented in Rome in 1968.

The scientists collected a trove of germplasm: 621 total collections of seeds of Coffee arabica, which, following the mission, were sent to the Plant Introduction Station in Glenn Dale, Maryland for seedling production and distribution. Germination rates were above 90% in some collections and, from 488 introductions, resulted in 11,000 seedlings. On June 1, 1965, these seedlings were distributed to research stations across the world.

488 seedlings were sent to the Instituto Interamericano de Ciencias Agropecuarias (IICA) in Costa Rica. Like the station at Tingo Maria, IICA—known today as CATIE—which, like the station at Tingo Maria, was founded in 1942 during the United States’ wartime prioritization of research and the State Department’s efforts to influence Latin American politics. Beginning in 1948, the station began building an ex-situ collection of coffee germplasm to serve as a reference for research. This collection later would form the primary gene bank later used for genetic fingerprinting by RD2, CIRAD, WCR and other researchers.

According to the FAO mission report, seedlings were also sent from Glenn Dale to Peru: “at the Research Station, Tingo Maria.”(a list of accessions sent to Peru, which sample all regions surveyed, is listed beginning on Page 153 of the report). Of the 455 seedlings sent to Peru, the Experimental Station at Tingo Maria reported that a year later, in June 1966, approximately 434 had survived.

This introduction of germplasm from Ethiopia would become part of the crop improvement programs at Tingo Maria. But, after the FAO team’s 1968 report, no further or more contemporary record of those plantings—or any other records of any sort from the research station at Tingo Maria—exists.

By 1974, local newspapers “buzzed with tales of a brash new class of local ‘Narcos,’” based around Tingo Maria.

The U.S. leadership of the Tingo Maria agricultural research station ended abruptly in 1968 at the imposition of General Juan Velasco’s agrarian land reforms. The reforms dismantled the hacienda system, aiming to break up large estates and redistribute land to state-established agricultural cooperatives and promote the agricultural use of land by peasants. By then, the International Coffee Agreement had been in effect for six years, with an updated agreement ratified the same year as the land reforms designed to stabilize global coffee pricing by establishing export limits for member nations. Peru’s export quota in 1968, 740,000 bags, was just above 1/10 of Colombia’s quota; by the end of the 1970s, over 80% of this volume came from cooperatives, farmed by indigenous people and campesinos. But the state left the cooperatives underfunded and failed to provide services outside of that bureaucratic structure, leaving campesinos with little market access, no legal protections, limited schooling and health services, and no political representation under a military regime that suspended elections when it rose to power.

In this political vacuum, tensions rose—with leftist opposition to the government rising and regional authorities growing to fill the absence of services from the central state.

Amidst this tension, the Marxist-Lenininist-Maoist inspired Sendero Luminoso movement emerged. Founded in Lima in 1969 by Abimael Guzmán, a philosophy professor at San Cristóbal of Huamanga University, and a group of his students, the group spread their movement by embedding itself in rural communities in Ayacucho, reframing their Maoist philosophies to respond to the marginalization of these communities by Lima. They encoded their ideology in local histories of racial exclusion and rural neglect, using a campaign of education and literacy to ingrain themselves in the countryside and filling a void left by the state.

When, in 1980, the military government of Peru allowed elections for the first time since 1968, Sendero Luminoso declined to participate, instead burning ballot boxes on May 17 in Chuschi, marking the start of their “people’s war.” As the movement gained strength in the Andean highlands and violence escalated, the federal government intervened, responding with reprisals, indiscriminate repression, massacres and disappearances—supporting the SL’s narrative that the government in Lima was corrupt, racist and disinterested in the lives of the indigenous and rural peasants, aligning their interests further.

Meanwhile, as the appetite of cocaine among the American public grew, so too did cultivation of coca in the Andean jungles of Peru and the Upper Huallaga Valley around Tingo Maria. While coca has a long history of use by indigenous peoples—chewed or prepared as a tea for its mild stimulating effects, said to relieve the symptoms of elevation sickness—this type of intensive production offered the opportunity for farmers to earn more money than coffee, which by 1980 covered some 153,000 hectares of Peru—47,404 hectares of which was around the Upper Huallaga Valley.

While coffee had soared to a record high price of $3.40 per pound in 1977 in the wake of the 1975 “Black Frost” in Brazil, when production and demand returned to normal in 1978, the market fell sharply to a three-year low of $1.06 per pound.

Coca offered distinct advantages over coffee: stable farmgate pricing, immediate cash payment, as many as 6 harvests per year, little labor requirements, few infrastructure needs and little risk of single-event failure events like frost. And so the area around Tingo Maria—once known for coffee—became a center for coca production in Peru as thousands of peasants poured into the area in the 1970s to grow the alkaloid-laden shrub.

By the early 1980s, the United States, engaged in the Reagan administration’s War on Drugs, embarked on a strategy of crop replacement and eradication in the Upper Huallaga Valley and other parts of Peru, providing funding and assistance to the Peruvian government in efforts to destroy coca plantings where they found them while attempting to incentivize alternate crops like coffee, cacao, tobacco, bananas and corn.

For the Shining Path, this offered an opportunity for the movement to ingratiate itself with the local population by serving as protection from the government and police against destruction of the valuable crop. Funding their operations by taxing traffickers and refiners, the rebels positioned themselves as armed regulators of the narco trade around the region. As a result, “between 1984 and 1990, [Government of Peru] officials responded to heightened insecurity by abandoning the region to narco-traffickers and the Sendero Luminoso.”

As a result of the threat posed by narcotraffickers and the SL, by 1984, the United States suspended its direct participation in the program of coca eradication, expatriating Americans working on the efforts in Peru while continuing funding for their partners in the Peruvian government. The Shining Path’s actions—which suited the American administration’s narrative—made news in the United States. A piece in The New York Times from November 1984 described an attack by the SL on the U.S. financed Coca Reduction Organization by 50 men with submachine guns:

All those killed in the attack, which took place early Saturday, were identified as Peruvian employees of the Coca Reduction Organization. The group is taking part in a $30 million program that the United States is financing to cut the production of coca along the Huallaga River, where most of the illegal coca in Peru is grown.

A 1987 article in the LA Times reported:

Shining Path rebels burned Tocache’s city hall to the ground in April and ordered the mayor, the prefect and other officials out of town. The guerrillas named “delegates” to collect taxes and maintain essential public services such as electricity and water, according to townspeople.

“There still are no civilian authorities here,” said Vidal. “They refuse to return to their posts because they fear we will leave and the terrorists will come back and kill them for collaborating.”

The guerrillas have discovered they can easily win support by presenting themselves as the defenders of coca farmers, who are angry at the U.S.-financed coca eradication program. The Shining Path has ambushed and killed workers in the eradication effort as part of its campaign of terror.

A report from the American Embassy in Lima summarized the violence, noting that “In 1986, the situation worsened when SL started selective assassinations of the mayors of Tingo Maria, Pumahuasi, Augayacu, and Pueblo Nuevo” as well as “destruction of valley infrastructure.” As the influence and control of the government collapsed, the Sendero Luminoso expanded their campaign of extortion—targeting cooperatives in the Huallaga River Valley and the research station in Tingo Maria. According to a USAID report titled “Selva Economic Revitalization Project”:

Almost no support for applied or basic research has existed since 1987. This lack of funds for applied or basic research was the result of destruction of the experiment station at Tulumayo. In September 1984, an attack on the experiment station was staged by SL. This attack destroyed the meteorological station, offices and laboratories of Servicio Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología (SENAMHI), as well as two electrical generators.

Then: “In January 1986, the SL attacked the agricultural experimentation station at Tulumayo and destroyed the labs, the library, field equipment and vehicles. In 1987, the SL again attacked the station and destroyed records of on-going field investigations.

In August 1988, the SL attacked again, for a third time—dynamiting everything that remained. As reported by the American embassy: “There was another attack on the Tulumayo agricultural experimental station that completely destroyed it. With it were lost the records of over 50 years of experiments on crops adaptable to the [Upper Huallaga Valley] environment.”

All of the records kept there—of field trials past and present, of germplasm and varieties collected from around the world including during the FAO mission in 1964, of distributions of seeds and seedlings—were lost.

I knew from the RD2 report that there had to be some common lineage between the variety called SL-09 and the one we called Inca Gesha. I knew that it wasn’t Gesha, even though I’d been able to establish that, at least at some point in and possibly before 1966, Gesha types had been distributed to Peru and grown near Tingo Maria and knew that, in the mid-2010s, Gesha seeds had been sprouted and distributed among friends.

Coffee trees produce recalcitrant seeds; that is to say, the seeds cannot germinate after being dried and frozen, and so in order to preserve genetic material for study or breeding, it must be grown and kept alive in the field. This type of collection—the one at Scott Labs, and at CATIE, and elsewhere in the world—is known ex situ in field conditions outside of where it historically grows.

Preserving this material can pose challenges—it requires that trees be kept alive, free from pests or disease. A 2019 inventory of the collection at CATIE revealed that 80 total accessions had been lost, fifty-six of which were C. arabica, making these varieties inaccessible either for genetic study or future breeding work. Of the 80 lost accessions, two were from the FAO mission—while another 50% of the 202 ‘threatened’ accessions were from the 1964 mission.

It can be difficult to ensure the genetic stability of lines, particularly when new generations are grown from the seeds produced by the collection. While some studies support the widely-believed notion that Arabica self-pollinates 85-90% of the time and that the “preferred autogamic reproductive fashion of the species allows only a 10% of cross fertilization”, “recent works in Ethiopian forests show that this share could go up to more than 50%,” and further, “several studies corroborate that coffee pollen can be transported by wind or insects over a distance of up to 2 km.” Even if low in probability, though they were planted in distinct, separate blocks, the varieties at Scott Labs could possibly have cross-pollinated, with the resulting fruits being used for subsequent field trials. And with the heterogenous nature of the blocks called “French Mission”, this seems even more likely still.

And, of course: genetic mutations occur naturally and randomly in all life.

Through these phenomena—mutation, adaptation, selection and hybridization—occurring together or apart can, over time, result in genetic drift in a population—even when the starting material was genetically identical (For this reason, some producers of highly-prized Panamanian Gesha practice cloning of their award-winning trees rather than propagating new generations from seed so as to ensure exact gene copies between them). That is, because they are alive and interacting with each other and the environment, in the context of field trials or on small-scale farms operated by campesinos, a degree of genetic drift can occur even amongst trees of verified genetic origin—creating evolutionary forks that eventually may result in altogether new varieties.

Genetic studies can determine the degree to which these shifts may have occurred. The only germplasm collection existing in Peru today lives on the La Génova property of the National Agrarian University La Molina in Junín started in 2011, containing some 211 accessions collected from 11 coffee-growing regions of Peru plus 19 cultivars introduced from Brazil. A 2014-2015 catalog of the taxonomy was produced evaluating the morphological and agronomic characteristics of the accessions using 16 qualitative and 28 quantitative descriptors. The study showed that the different accessions showed greater variability for the quantitative characteristics, and for the qualitative characteristics a certain polymorphism was observed.

A later 2021 study in the Chilean Journal of Agricultural Research examined the genetic diversity of the collection using microsatellite markers and Sequence-Related Amplified Polymorphism method of analysis. Rather than producing a forensic identification of an individual tree, this type of genetic assay is able to make a determination of how related a population is. In other words, it’s able to distinguish between closely-related Arabicas by clustering similar varieties. Rather than having the ability to answer specifically the question, “Is this unknown tree Gesha?” it can determine if it exists in the same cluster of trees which may be related to Gesha. This is useful, however; if we’re able to detect overlaps and relations in the broader population, it can provide insights into the historicity of certain cultivars present.

The study concluded that “The high genetic differentiation and genetic structuring of the accessions would indicate that the cultivars, from which the accessions were originated, have been preserved over time,” and further, that “The genetic diversity of Peruvian coffee might be the consequence of a long history of introductions of cultivars from different origins.” The authors charge that “these accessions might not be very different from the cultivars from which they were generated, after being introduced to Peru” and noted a relatively high level of genetic diversity among Peruvian cultivars.

And, notably, the authors observe that it’s possible “that in some areas of Peru there are still descendants from a group of genotypes arrived in Peru from Ethiopia and Eritrea thanks to a FAO expedition of 1964-1965.”

I scoured the inventory of varieties grown at Scott Labs and cross-referenced them to those I’d been able to establish were—or had once been—grown in Peru.

If SL-09 was a single-tree selection of unknown origin from Scott Labs plantings, it had to derive from the collection there. I’d hoped to, somehow, figure out which collection.

It was conceivable that, like SL-34, which was a single-tree selection from the heterogenous French Mission Bourbon group that contained material from Yemen, SL-09, another single-tree selection, could have originated with that group. But while they share some attributes (both having broad leaves, for example, and both highly susceptible to Coffee Berry Disease), there are differences: SL-09 new leaves are copper, while SL-34 are typically described as bronze (though sometimes as copper). They are genetically and morphologically different—even if related in the same descended-from-Ethiopia event cluster.

But as I looked closer, I was struck by an oddity. Among those varieties that I expected to see—because of the FAO mission, because of the common source of material grown in Peru traditionally—I saw a cultivar that I’d never heard of before, which was included on the original list of variety trials intended for Tingo Maria documented in the 1950s and was introduced to Scott Labs in 1931.

First discovered in Java in the late 1880s at the the Pantjoer estate in Java, around the same time as the first introductions from Yemen to Kenya—Columnaris was established commercially in Puerto Rico because of its “excellent” cup quality and “amount of yield.” Originally selected by the Dutch coffee planter Ottoländer, no records exist of its origins as he died without leaving records—but based on the historical movement of coffee to Southeast Asia, it’s logical to assume that it shares a pathway to Indonesia from Ethiopian “Abyssinian” varieties via Yemen.

That could fit the “Ethiopian Legacy” pathway uncovered by the RD2 report. What if SL-09—and, Inca Gesha, coincidentally, by extension—was actually Columnaris?

Columnaris first produced cherry in Puerto Rico at the experimental station in 1912, “a year later than the average Arabian coffee began to bear”—a tendency for later bearing which was apparently confirmed in subsequent plantings in 1915 which came to bear in 1919. The of Columnaris yields were noted to be “satisfactory and decidedly so in the lower, more fertile section of the planting.” The tree was noted in a 1914 Report of the Assistant Horticulturist at the Puerto Rico Federal experiment station to be “more vigorous and grows taller than the typical Porto Rican coffee” and with a bean size that was “a trifle smaller” than Puerto Rican local cultivars.

World Coffee Survey, published by FAO, observed that Columnaris (referred to there as columnaris Ottoländer ex Cramer, named for its breeder and Cramer, who described it) was grown in Peru by the time of the report’s publication in 1959 though in very small amounts, consistent with variety trials: “The typica variety of C. arabica is practically the only one grown in Peru; very small amounts of bourbon, maragogipe and columnaris being cultivated.”

The first variety trials conducted by Scott Labs, as reported in a 1940 Coffee Board of Kenya Bulletin, included Columnaris. In that first trial, the Columnaris trees “show no debilitation, due chiefly to the fact that it is a ‘shy bearer’.” A 1956 Coffee Board of Kenya Bulletin noted that Columnaris “produces very long and whippy laterals, profuse secondary growth, narrow mature leaves and copper terminal leaves. The shy bearing tendency, especially at higher altitudes, has been confirmed by trials in Kenya.” Meanwhile, SL-09 was observed to “yield heavy crops of good quality at the middle altitudes.”

In addition to sharing copper terminal leaves like SL-09, Columnaris was observed by Scott Labs to be very susceptible to Coffee Berry Disease, a trait which made SL-09 unsuitable for distribution. Further, while both SL-09 and Columnaris were theoretically susceptible to the same strains of Hemileia vastatrix (I, II, VII, XV), they were reported in Kenya only to show infection with race II—a circumstantial commonality shared between only 9 of 38 varieties studied at Scott Labs including SL-18, which was, like SL-09, described as broad-leafed and copper-tipped but unlike SL-09 is known to have come from a selection from D.R. I in 1936 (itself a block of unknown origins but likely the Yemen-originated French Mission variety).

In a paper published in 2011 in the International Journal of Biodiversity and Conservation, researchers used molecular markers to analyze the genetic diversity of Kenyan commercial coffee and Kenyan museum collections. The RAPD + limited SSR method used by the researchers is now largely considered obsolete; it does not offer high-confidence discrimination between closely-related Arabica types, distinguish between different Ethiopian landraces at high resolution, nor provide forensic-grade identifications like the methods used by RD2. But: it does offer the ability to identify introgressed materials, show narrow diversity among C. arabica and cluster varieties by related genotypes. Among those genotypes tested included SL-34, SL-28 and K7 and Geisha 11 from Kenya—and Columnaris from Puerto Rico. According to the authors,

Close genetic proximity was observed among the existing traditional commercial varieties in Kenya, namely SL28, SL34 and K7. These results are in agreement with the work of Agwanda et al. (1997) and Hue (2005) which revealed high genetic similarity between Kenyan traditional commercial varieties.

Appearing together in a cluster of related varieties were Ethiopian landraces and varieties that would be expected—Mocha, Geisha 10, and Harrar—as well as Columnaris:

The 1994 catalog of the CATIE germplasm bank shows three introductions of Columnaris to the database, 2144 (IAN-95), 2397 and 3411, coming from Guatemala in 1952; Puerto Rico in 1953; and Boquete, Panama in 1956, respectively, more than 20 years after its introduction to Kenya but indicating that the variety was grown widely across the Western Hemisphere, fitting earlier descriptions of distribution of non-Bourbon and non-Typica cultivars. Notably, the CATIE collection does not include material from the original Columnaris collection in Kenya—and thus, we lack a true genetic reference for it.

It is entirely possible that there is no relation; the latency between its original discovery and later distribution may create issues with the genetic integrity of the variety, particularly since “Columnaris” appears to have been used as a morphological variety name rather than a verified genetic lineage. In other words—it is likely heterogenous, and types called “Columnaris” may not be representative of others. And, of course, as noted by Dr. Montagnon and his collaborators about a different SL variety, SL-06, in a 2021 paper: it’s not possible to discount the possibility of “potential mislabeling or mixing anywhere between the Kenyan research stations and the CATIE germplasm collection.”

As cultivation of Arabica increased and spread in Peru, plantings were dominated by Typica; a crop replacement scheme funded by the U.S. through USAID increased the amount of cultivation of Caturra and Bourbon, particularly in the South of Peru, but contemporary adoption of Gesha seeds of verified origins from Panama has been motivated by a desire for higher premiums paid by specialty buyers.

Adoption of new varieties tends to be a local phenomenon; farmers notice desirable traits in a tree or block of their farm and select those trees for breeding or cloning, increasing the number of plantings in the hopes of expressing those traits in a productive population.

This practice of adaptive genetic management can improve the resiliency and profitability of a farm—as well as lead to the rapid proliferation of genetic material of otherwise unknown origins. Gesha, for example, gained popularity initially not because of its cup quality but because of its resistance to roya; so too did Pink Bourbon. Chiroso, once believed to be a mutation of Caturra or Bourbon, was adopted because of its high yields, rust resistance and ease of harvesting. Once a cultivar is established locally, it tends to, without a single-event failure, continue; meanwhile, its true origins can quickly become lost to time, even as its number of plantings expand.

It’s entirely plausible that Columnaris—or some other Ethiopian-type coffee stemming from the FAO missions or earlier—found its way across the Andean highlands as peasants migrated away from Tingo Maria and the Upper Huallaga Valley for safer pastures, propagating new trees from seed they’d collected and transported.

But, whatever it is, the tree called “Inca Gesha” is cultivated widely across Peru and is renowned by buyers for its quality and Ethiopian-like cup profile. Even if it comes from the same genetic stock as SL-09 and thus could be regarded as the same, Inca Gesha isn’t SL-09 and it can’t be—it came from other sources, independent of the work done by Scott Labs in Kenya a century ago, which remained Kenya-bound. It doesn’t come from Kenya—so why would it be named as such?

Inca Gesha, any apparent introgression or heterogeneity notwithstanding, might as well be regarded as a distinct variety in its own right, adapted to its local environment and attached to a local mythology, history and sense of place.

And perhaps—with its origins lost to time—instead of naming it after a genetic reference never distributed, we should call this cultivar by the name given to it by the people who grow it.

UPDATE 2025-01-07: I emailed with Dr. Montagnon several times through the research and writing of this piece. Following its initial publication, I shared a link to the post. He was kind enough to share a few comments:

Tags: coffee cultivars ethiopia gesha green coffee history inca gesha kenya origins peru varitiesThe columnar hypothesis you mention is possible.

More generally, your text suggests an additional hypothesis worth considering. The SL cultivars in Scott Lab were identified as individual trees within existing populations, not created through controlled crosses. This means the original “mother populations” may already have been genetically uniform. From my work on Yemeni coffee genetics, I would even suggest that SL-type material (including SL28 and SL34) likely already existed in Yemen as individual cultivars, unidentified and unnamed at the time. If British settlers were indeed growing coffee in Peru around that period, is it not conceivable that seeds sourced from peers in India or East Africa (utlimately coming from Yemen) were introduced, and that—purely by chance—some of these seeds belonged to populations that would later be identified in Kenya as SL-type material (including what we now call SL-09)? Such material could then have remained present, but latent and unnamed, in Peru until much later.

This remains speculative, of course, but might be consistent with current genetic evidence.

Super interesting research and great work. I enjoyed the article very much. It is quite mindblowing how coffee made its way all around the coffee belt from Ethiopia and Yemen.