Publisher’s note: I’d heard of Thai before I met her, but in the years that followed we became fast friends with a common taste in memes and irreverent ideas. When she approached me about contributing a guest piece to my blog, I was more than enthusiastic; the work that Thai and Hana at 96b have undertaken is among the most fascinating vocational work I’ve seen in coffee. If not for the devastation of the American military actions in Vietnam, it’s quite possible that the genetic collections of Excelsa contained around Khe Sanh might be the species’ equivalent of the CATIE institute and may have resulted in commercialization of the species decades ago. Instead, 96b is doing that work on their own: defining the phenotypes present, rigorously cupping them, and iterating their processing to improve the acceptance and marketability of this fascinating species each season.

Wounded soldiers awaiting helicopter evacuation in 1968 after the siege of Khe Sanh, South Vietnam. Dana Stone/United Press International. Retrieved from The New York Times.

On January 21, 1968, at 00:30, hundreds of mortar rounds, rockets, and grenades slammed into the American Marine outpost atop 861, the hill overlooking US Marine Corps Khe Sanh Combat Base. Thirty minutes later, 300 soldiers of North Vietnamese People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) charged through the rain of hellfire, engaging in hand-to-hand fighting with US troops. At 05:30, mortar rounds, artillery shells, and rockets continued their descent into the base, leveling ground structures and sending marine troops scrambling underground to take shelter. A PAVN rocket hit an ammunition dump at the end of the airstrip, detonating 1,500 tons of ordnance. Amidst the blinding explosion, helicopters tumbled, buildings collapsed, rifle, mortar, and artillery detonated into a torrent of fire. A cache of tear gas was hit, releasing a thick cloud of choking vapor. Power went down, pitching half of the airstrip into darkness, lighted only by round after devastating round of mortars and rockets.1

While the fighting raged on Hill 861, three kilometres away a PAVN troop launched an attack on Khe Sanh village and soon overwhelmed the US platoon stationed there. As dawn broke, civilians awoke to a new reality: war had arrived. Roaring and unforgiving.

Huddled inside their house with their two young children, Madeleine and Félix Poilane heard helicopters circling above over the din of incessant machine gun fire. Sunday was for Mass, but with the intense battle, they decided to stay home. American B-52s were blanketing the landscape with bombs, so, to protect the house, Félix began to call the coffee plantation workers. By evening, the family settled in their cellar and listened to the unexpected, menacing silence—a counterpoint to the infernal bombardment of the previous 24 hours.2

On January 22, American soldiers and supplies arrived by air. The sky was still lit up with PAVN’s anti-aircraft fire. General Westmoreland, however, was confident that with the additional fire-power the Marines could hold Khe Sanh. Thus started the 77-day Khe Sanh siege, now remembered as one of the fiercest in history. Over the length of the siege, US Air Force bombers dropped 14,223 tons of bombs, rockets, and other munitions; the Marine Air Wing contributed an additional 17,015 tons of ordinance, while the Navy planes flew into Khe Sanh with 7,941 tons. 2,700 B-52 bombers pummeled Khe Sanh with a staggering average of 1,300 tons of bombs every day of the siege—five tons of bombs for every one of the estimated 20,000 PAVN soldiers believed to be in the Khe Sanh area.3

Over the siege, 110,000 tons of bombs were dropped in an area of under 200km², barely four times the size of the island of Manhattan.4

Returning to January 22nd, Félix told Madeleine to pack their belongings, without informing her that when they left, they would likely never return. By 16:00, as Félix returned after a day of helping locals evacuate to the US military base, it was too dangerous to remain. As night fell, the Poilane family, carrying the bare essentials, were the last to leave their coffee plantation.

Poilane family in 1964: parents Félix and Madeleine, daughter Françoise and son Jean-Marie. From Jean-Marie Poilane personal collection.

They turned off their refrigerator, locked the door, released their pet deer Bambi, collected the money from the six tons of coffee they’d just sold and drove to the US base in their beat up Citroën 2CV to be be evacuated to Da Nang in a Lockheed C-130 with more than 1100 other local civilians.

Madeleine and her children, Françoise (aged 8) and Jean-Marie (aged 5), would never see their plantation again.

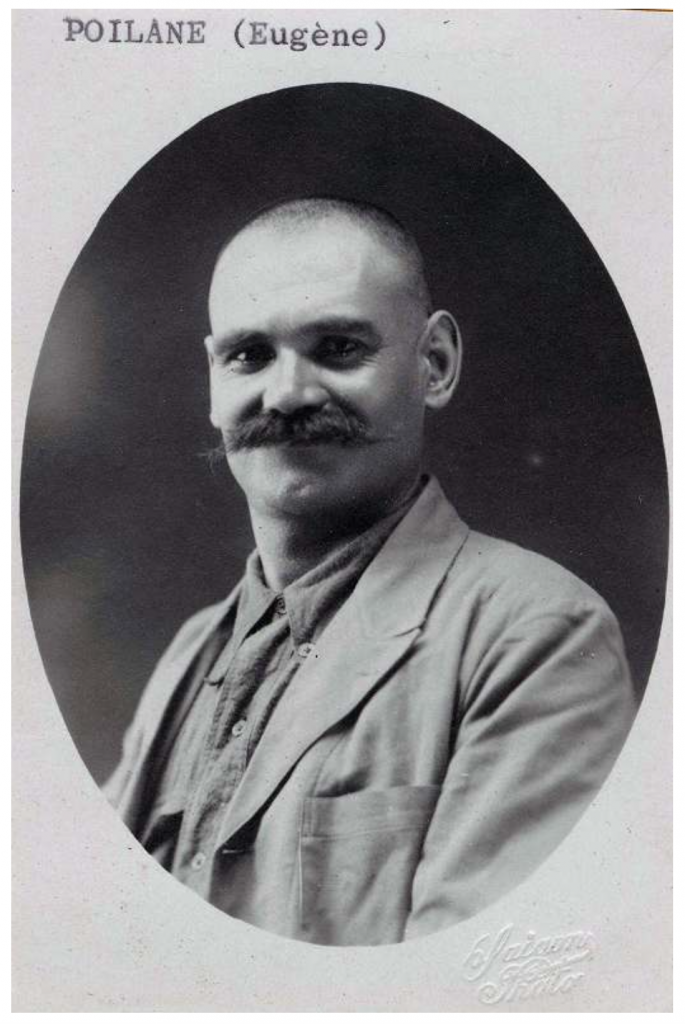

In 1918, on one of his travels, Eugène Poilane arrived in Khe Sanh, then called Cu-Bach. At that time, Cu-Bach was a plateau of red earth at an elevation of 483 metres, about 20km from the Lao border, more jungle than village. There was no road and only one house, belonging to the French engineer supervising the construction of Colonial Route 9 (now called Quoc Lo So 9), connecting Laos to the Vietnamese coast. There were no ethnic Vietnamese; only a village of the Bru (an indigenous ethnic group living in Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand) nearby. He was immediately captivated by the land’s boundless vegetation and its endless red earth.5

Born in 1888 to a poor peasant family in Saint-Sauveur de Landemont, France, Eugène Poilane the year of his mother’s death at age 10. As a child, he dreamt of travel and discovery, and enlisted in the French army at 19, joining the 3rd Colonial Artillery. He left for Cochinchina (Southern Vietnam) in 1909 where he was assigned to the 7th Mountain Battery, then to Saigon Pyrotechnics, and in 1914 ended up as a non-commissioned officer in a platoon focusing on agricultural work.

In the metropolitan Saigon, he would frequently visit the Saigon Botanical Garden (known nowadays as the Saigon Zoo & Botanical Gardens), then a veritable trove of flora and fauna of “Indochina,” and a must-visit for any visitor to the city. In 1918, his life changed, when he introduced himself to Auguste Chevalier, the famous French explorer, botanist, taxonomist, and coffee expert, who was residing in Indochina between 1917 and 1919.

Chevalier, whose contribution to coffee was and remains immensurable (including his creation of the classic series of publications entitled Les Caféiers du Globe), was immediately impressed by Poilane. In Poilane he saw a soldier without any qualification but with the field experience and courage of a fearless explorer, the intuition of a born-naturalist, and a keen eye and boundless curiosity for nature. In 1919, Chevalier managed to get him seconded to the newly established Saigon Scientific Institute (L’Institut Scientifique de Saigon) as a prospector botanist. Founded in 1918 by Albert Sarraut, the then Governor-General of French Indochina who would later twice become French Prime Minister, the institute aimed to centralise and undertake research on the flora and fauna of Indochina and to improve scientific understanding of agriculture and plant diseases. Like similar institutions set up by colonial administrations at the time such as the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew in London, Peradeniya in Kandy, or Buitenzorg in Java, the aim of these institutes was, amongst others, to discover and propagate plants most useful for the various colonial empires.

Chevalier trained Poilane during prospecting trips to Gia-Ray and Ca-Mau (nowadays Dong Nai and Ca Mau) in Cochinchina, teaching him how to collect and prepare botanical specimens. In 1922, Poilane was promoted to Forestry Agent and, in 1928, became a correspondent for the National Museum of Natural History in Paris. Due to his self-made background, Poilane didn’t fit into the pedigreed scientists that were his colleagues; despite this, a meager salary and a constant struggle to gain recognition, Poilane went on to become an intrepid explorer, reaching remote corners of Indochina on arduous missions. He would often travel on foot under the tropical sun, blazing his own trails and sleeping in tents. Beyond collecting botanical specimens, he was interested in animals, from tigers to slugs, bats to butterflies. He was fascinated in the production of fish sauce, the relationships between Indochinese ethnic groups, and their customs and their lifestyles.

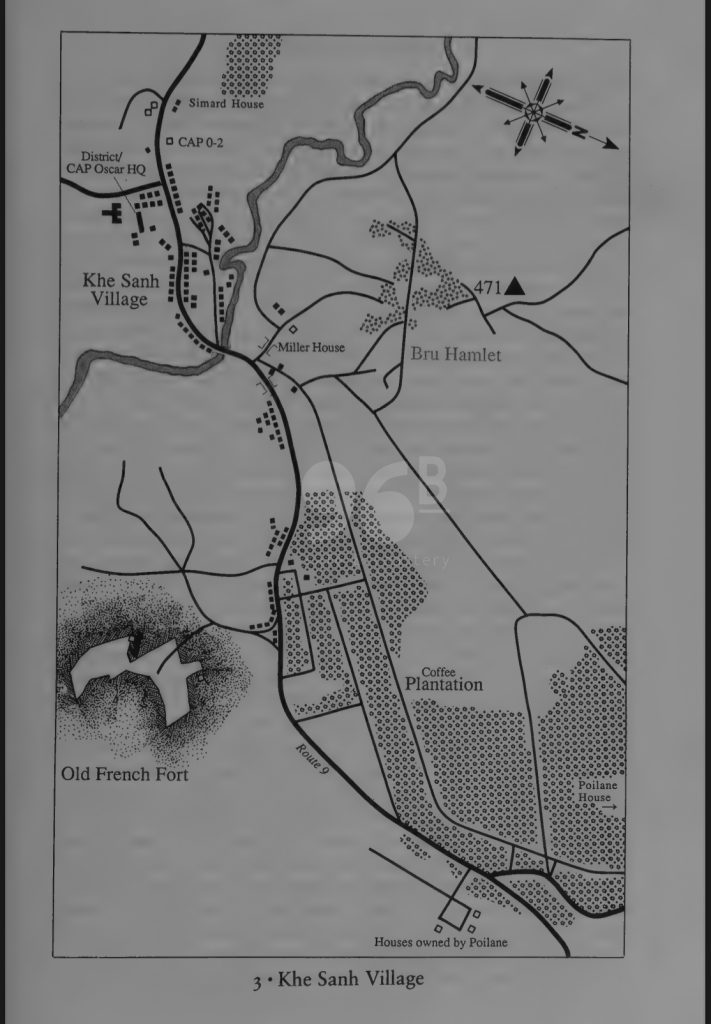

Khe Sanh village and Poilane plantation map from Prados, J., & Stubbe, R. W. (1991)

Between 1922 and 1947, Poilane sent between 1,500 and 5,000 specimens per year to the Museum in Paris. His collections, still held there today, number more than 36,0006; each was meticulously recorded, with rich descriptions of each specimen and its relations to the environment and local use and knowledge. His discoveries point to 21 new plant species, previously unknown to science, and he provided the second known specimens of 19 others. The genera Poilania and Poilaniella are named in his honour. The Sonnerat Database estimates that between 20% to 30% of herbaria collected by Poilane are nomenclatural types, meaning that his specimens are the objective reference points to which a scientific name is permanently attached.7

His travels took him to secluded mountains of Laos, to the uncharted hills of Annam (Central Vietnam), to the peak of Fansipan (the highest mountain in Indochina) in Tonkin (North Vietnam). But the landscape of Khe Sanh remained his favourite. This is where, in 1924, Poilane asked the French authorities for a concession of these lands.8 The authorities gave him a lease of 5 years, waiting to see what this daring botanist soldier could do.

In 1926, together with his first wife, Yvonne Bourdeauducq, and some hired workers, they built a thatched hut, cleared the land, and slowly set up a coffee plantation and an experimental orchard, all in between his prospecting work. After a trip to Tonkin, he brought back nine Charicoffee seeds and created a nursery from them.9 Arduous work ensued, both in the field and in dealing with the temperamental weather and in coping with loneliness and living in wilderness (tigers being a constant menace).10 While plantings typically produce in the first 3-5 years, it took the family ten years until they could reap their first coffee harvest.

Apart from coffee, Poilane was also devoted to growing fruit trees. He imported scions from France, Japan and other countries to graft them to local rootstocks (a famous example being grafting French grapes on indigenous vines), successfully introducing grapevines, peach, plum, pear, chestnut, walnut, hazelnut, and kola trees to Khe Sanh.11

Little by little, the plantation and the family grew (the couple would have three children, one of them Félix). The village of Khe Sanh began to take shape, attracting other planters such as Mr. Laval, a retired French officer and later Mr. Simard, or Mr. and Mrs. Rome, whose plantation eventually went to Mr. Llinarès. Vietnamese began to arrive and settle in, first traders, then their families. Impressed with his work, the French authorities conceded 2,000 hectares to the Poilane family. Their plantation was situated right next to Route 9 and extended throughout the area subsequently occupied by Khe Sanh Combat Base.12 When the couple divorced in 1939, Bourdeauducq moved 1km down the road and started her own plantation. This would be the land Félix and Madeleine took care of after they moved to Vietnam in December 1957.

By the time they left Khe Sanh in 1968, the young Poilanes were producing 23 to 24 tons of coffee per year, employing 20 to 50 Bru employees daily.13 Over 11 years, their coffees would be sent down the coast to abroad ships en route to France, westward to be traded in Savannakhet, or, when the roads became too unsafe due to incessant fighting, boarding American planes to arrive in Hue and Danang, before being sold to the market.

The Poilanes’ last harvest in 1968 would lay inside Jeanne d’Arc school in Hue, the tragic heartland of the fierce 1968 Tet Offensive. Several tons of coffee would fall into the hands of the communist force. Most of these coffees were called Chari, known nowadays as Coffea dewevrei, or by the vernacular name Excelsa.

1920-1929 Phú Thọ – Caféier “Chari”. Photographer unknown.

The first time I saw the name Chari was in this striking picture, taken in Phu Tho, a province in Northern Vietnam. Next to the intensely-staring Vietnamese man is the unmistakable sight of an Excelsa tree.

My efforts to understand the word Chari has taken me on an unexpected journey, full of convoluted forces, colourful characters, and painful stories. After three years of trying to connect the dots to understand the rise and fall of Liberica (Coffea liberica) and Excelsa, I have come to learn more about this forgotten chapter of coffee. But more importantly, to know coffee history is to be faced with the history of empires, of colonialism, of forces big and small, systematic and individual, that shape the landscape we are living in today.

Like cinchona, rubber, sugarcane, or tea, the story of coffee is that of colonisation, exploitation, and commoditisation. The history of Arabica (Coffea arabica) and robusta (C.canephora) and how they spread across the globe has been told numerous times, but what is lost in the narrative is the story of other coffee species, how they were brought from their birthplace in Africa to the other side of the earth, their fleeting moments of glory in world commodities, the spark of hope they briefly lighted up, and their swift demise in planters’ dreams and practice. These transient stories are more than a curiosity devoured by coffee nerds to impress other nerds at parties (me being one), but function as a tale, cautionary and inspiring in equal measures, for our modern coffee landscape.

My obsession with Excelsa (Coffea dewevrei) and Liberica (Coffea liberica) started in 2017 when I came across 96B Experiment, a tiny cafe in Ho Chi Minh City (otherwise known as Saigon), and tasted some truly strange coffee. The owner, Hana, told me it was ca phe mit (jackfruit coffee), otherwise known as Liberica (after August 2025, we would call it Excelsa). It was unlike anything I had ever tasted, with a palpable and jarring sweetness.The intense notes of ripe fruit were unforgettable.

After a few years working in Hong Kong, I decided to return to Vietnam and joined 96B, eventually becoming the co-owner of the company. In 2020, we changed the cafe name to 96B cafe & roastery, but our core obsession and product remained the same: to process, roast, serve, and promote this coffee.

After much trial and error, both in figuring a core region for our team to source Excelsa and in tweaking with various processing and drying methods, we eventually found our roots in Huong Phung, Quang Tri. Quang Tri is not the first region one would associate with coffee (my very Vietnamese parents were surprised to hear that I was going to Quang Tri to check out the harvest). Most international buyers think of Lam Dong for high-grown Arabica, or the fertile Central Highlands for Robusta. But there, in Quang Tri, the trees were bountiful and beautiful. They were not grown in plantations, but could be found as fence rows or as spontaneous clusters of gorgeous trees. The flowers varied in size and corolla; the leaves could be as large as 30cm x 10cm; the trees could reach a height of 12 metres; and the cherries ripen to purple, crimson, bright red, or orange. Seeing an Excelsa tree for the first time remains one of my most impressive coffee memories.

This coffee is also challenging—not necessarily in growing, but in harvesting, as the tall trees demand pickers climb ladders to harvest the ripened cherries. Processing is another obstacle, as the thick mucilage and high sugar content often quickly turn them into an undrinkable mess. But the most difficult aspects were the lack of research, both in processing and roasting, and the lack of interest. For years, we felt we were alone in figuring this coffee out. We had one chance per year, during harvest season, to crack the code, which proved to be as enigmatic as the history of how this coffee species ended up in this tiny piece of land.

A cursory glance at coffee in Vietnam on the Internet points to a few superficial sources, consisting of generic information such as the French were the first to bring coffee to Vietnam, or Vietnam being the biggest Robusta producer and the second biggest coffee exporter in the world. The devils, as always, are in the details. Yes, the French brought coffee to Vietnam in the mid-19th century, but which coffee? Yes, coffees are grown in the Central Highlands, but how did they end up in other unexpected pockets in the country, like Quang Tri? Yes, Robusta is King in Vietnam, but where did Liberica and Excelsa come from?

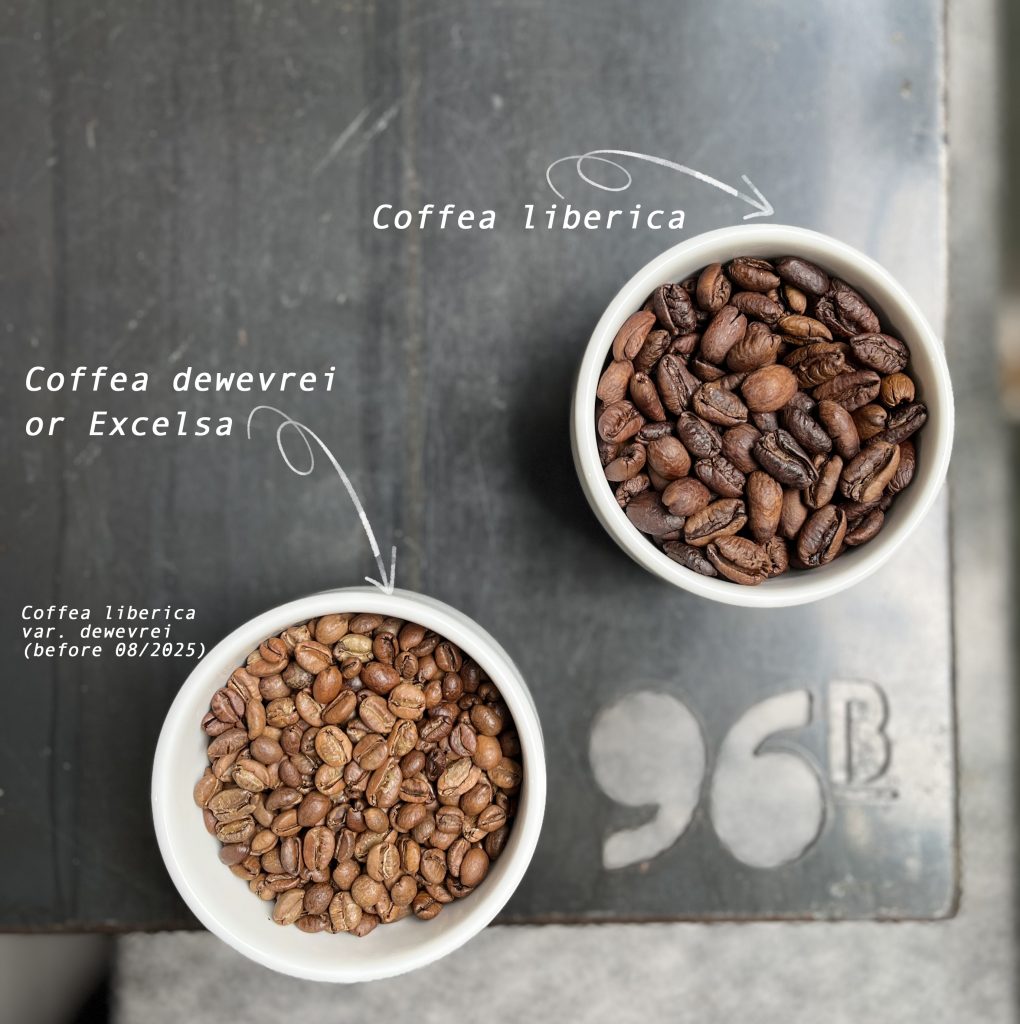

First: let’s talk names. Before August 2025, Excelsa was listed as a variety under the species Coffea liberica (its full name was Coffea liberica var. dewevrei)14. In August 2025, Aaron Davis et al. published a new paper, using genomic, morphological and spatial analyses to divide C. liberica into three distinct species: C. liberica (liberica), C. dewevrei (excelsa) and C. klainei. With C. dewevrei and C. klainei reinstated (they used to be categorized as separate species, only to be merged under C. liberica, to be unmerged again), the total number of known Coffea species is, as of February 2026, 133.15

This is why 96B called our coffee “Liberica” before August 2025, knowing full well that it was Excelsa. Our Excelsa coffee project was named 96B Liberica Project, as it started in 2021. Nowadays, this coffee is still called Liberica or “jackfruit coffee” in Vietnam; I believe that it will be a while until the name Excelsa takes off, let alone the tongue-twister Dewevrei. Based on our own years of experience, we can confidently say that when you find “Liberica” in Vietnam, they are likely to be C. dewevrei (Excelsa). (Meanwhile, if you find “Liberica” in Malaysia, it is highly likely to be true C. liberica). While we would not make any definitive verdict on the debate of Liberica vs Excelsa in Vietnam until a wide-ranging genetic study is conducted, history would support our conclusion.

Until the late nineteenth century, Arabica dominated the global coffee industry. From its earlier frontiers of Western Ethiopia and South Sudan, and the initial plantation in Yemen, Arabica was brought by European colonial settlers to stranger lands around the globe. Cultivation of coffee in the Dutch East Indies, the Caribbean, Ceylon, India, Central America, and Brazil, along with other crops such as sugarcane, cacao, rubber or opium, formed the backbone of the newfound wealth for Europe. But it was cinchona plants, whose barks contain quinine, a substance effective in curing malaria, that engineered the scramble for Africa and hence, accelerated the riches of empires. Before 1870, about 10% of Africa was controlled by Europeans; by the early 20th century, the figure was 90%. Sanghera argues that it was quinine, along with other technical advancement such as steamships and Maxim guns, that enabled Europe to extend its empire arms in a continent once called the White Man’s Grave.16

As European forces made their way deeper into Africa, new plants were “discovered”, a result partly of European botanists’ curiosity, partly in the spirit of adventure, but mostly in the service of satisfying the thirst for new resources and raw materials. Before the nineteenth century, coffee was synonymous with Arabica, as other beverage Coffea species were virtually unknown. With new trading posts set up and intrepid miles ventured deeper inland, new species were uncovered and documented. One of them was Liberica, then known as Liberian coffee.

Unlike the misnomer Arabica, implying that coffee was of Arabian origin rather than, say, Abyssinica or Aethiopica, Liberica carries the name of its native home: Liberia. In 1816, a group of white Americans founded the American Colonization Society (ACS), aiming to solve the “problem” of newly freed black slaves by sending them back to Africa. The Society would make repeated attempts to find a suitable location in West Africa, ranging from persuading local tribal leaders to sell their territories (to no avail) to outright coercion (to some success). A piece of land, bordered by nowadays Sierra Leone to the West, Guinea to the North and Ivory Coast to the East, was chosen as the permanent settlement. For protection against repeated attacks from local tribes, the settlers (composed mostly for freed American slaves) built fortifications around their new land. In 1824, the settlement was named Liberia.

According to McCook, one of the earliest mentions of coffee in Liberia was by Jehudi Ashmun, the U.S. Representative to Liberica, written in 1827.17 Ashmun contemplated the possibility of harnessing this new coffee as a potential valuable export for the new colony, as they were growing in great numbers along the coast. As early as 1828, the first shipment of Liberian coffee reached the US, sold to and consumed mostly by those associated with ACS. Until the 1860s, most Liberian coffee consumed within and exported outside of Liberia were wild coffee, as efforts to cultivate this species as a crop remained sporadic and futile.18 Davis et al., however, noted that from the early 1870s onwards, large-fruited Liberica phenotypes appeared more frequently, implying that these plants were intentionally selected.19 It was Edward Morris, a Philadelphian businessman, who brought Liberian coffee to the forefront of the American and Liberian market. Addressing the Liberian Union Agriculture Enterprise Co. in 1868, Morris extolled coffee as irreplaceable.20 “Its peculiar aroma cannot be imitated,” he reasoned, coffee is so unique that the “whole vegetable kingdom cannot afford a substitute.” Besides, with the cessation of slave trades to Brazil, he foresaw a decline in Brazilian coffee production, which would demand more supplies from other countries. Coupled with the rapidly increasing consumption of coffee in the US and in Europe, Morris believed that high prices for coffee were to follow. In this optimistic future, Liberia and its coffee, he believed, had a historic role to play.

The time for Liberian coffee would eventually come, but for a reason completely different from the scenario he contemplated.

The beginning of the end for Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) coffee started in 1869, just a year after Morriss’s pronouncement. Early in the year, a farmer in Madulsima district noticed orange spots on the leaves of coffee trees; soon, defoliation followed.21 Samples of the infected leaves were sent to the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew in London, catching the immediate interest of Joseph Dalton Hooker, the Gardens’ Director. Hooker engaged Miles Berkeley, a leading plant pathologist and cryptogamist of the day, to look into this curious fungus. Berkeley, which had analysed thousands of fungi and other plant diseases, identified it as a novel fungus. In November 1869, Berkeley and Broome described and illustrated the new fungus in The Gardeners’ Chronicle. This fungus received a name, Hemileia vastatrix: the devastator.

Within two years, the terror of these orange spots engulfed the whole island, once famed for lush coffee plantations extending as far as the eye could see. Commonly called Coffee Leaf Rust, the fungus annihilated the large plantations of Ceylon, rapidly devastating the total yield of coffee production on the island. To manage the rust, planters tinkered with moving plantations to higher elevations, used experimental fertilisers (both chemical and organic, local and imported) and chemical sprays, and planted new Arabica varieties. Nothing worked. Leaves kept falling, productivity continued to decrease, and new varieties succumbed to the rust like falling dominos.

A new approach was needed: instead of continuing with Arabica, why not try a new coffee species? Other species of Coffea had, by then, been provided with scientific names, including Liberica. In 1872, the first shipment of Liberian coffee seedlings were sent to Kew. Another separate shipment reached William Bull & Sons’ private plant nursery in Chelsea.22 It was Bull who gave Liberian coffee its name, Coffea liberica, in 1874.23 Liberica was soon introduced to Ceylon, both as living plants by George Carey in May 1873 and as seeds and seedlings produced at Kew Gardens and Bull’s nursery. Other British colonies followed suit, as Wardian cases of plants were sent eastward to Mauritius, India, Java, and westward to the West Indies islands (such as Jamaica, the Bahamas, Dominica, Montserrat, Grenada) and Brazil.24 Expectations were high. “Liberian Coffee, its gigantic size, its peculiarities as to climate, and its great promise were household words from Brazil to Burmah, from Jamaica to Ceylon; from Calcutta to Queensland,” mused Hooker.25 As the sun never set on the British empire, Liberica’s reach was rapidly globalised and global. These trees were observed to be highly resilient. With “its deep, strong tap-root, its thick, rough brown tree-like stem, its large foliage, and its robust habit altogether,…” Cruwell lauded in 1878, Liberica “…is eminently qualified . . . to withstand those prolonged droughts to which the “low-country” region is liable.”26 So enthusiastic at the prospect of a low-land compatible, potentially H. vastatrix-resilient species that a group of planters from Ceylon visited Liberia in 1875-76, to observe the native home of this coffee and to collect their own seeds.27 As the trees grew and started to bear fruits, Liberica signified hope for a new source of wealth, the power of scientific research, and the pride of empire. Reports from The Tropical Agriculturist lauded Liberian coffee as a new wonder species for planters in Ceylon.28

That said, Liberica was not an instant favourite amongst all the planters. Farmers in the Western hemisphere saw little value in this species, as they themselves were not experiencing coffee leaf rust on a large scale and saw no need for new blood on their plantations. The trees’ ability to grow in lowlands and under higher temperatures were not compelling enough, as sugar plantations had already dominated that landscape. In Africa, sporadic efforts to cultivate Liberica by European missionaries and settlers met with little enthusiasm.29 It was in British and Dutch Asian colonies, where coffee leaf rust was wielding its axes, that Liberica enjoyed its successes. These stretches of coffee lands, extending from India to Malaya (Malaysia), from Ceylon (Sri Lanka) to the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), are still growing Liberica today, albeit in small pockets.

Sandwiched between old empires of the British and the Dutch lay a peninsula, consisting of present-day Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. Later called Indochina, the French involvement in this region started with trade and missionary work. Like other European powers, France began to establish colonies from the 16th Century in the Americas, India, the Caribbean, and parts of Africa, but lost most of them to Britain and Spain. The second wave of French colonialism concentrated first in North Africa from the 1830s, before extending to the South Pacific and Indochina.

After the Treaty of Saigon was signed in 1862, Saigon (now called Ho Chi Minh City), the island of Poulo Condor (nowadays Con Dao), and three other southern provinces were ceded to France. In 1867, French Admiral Pierre de la Grandière forced the Vietnamese ruler to surrender three additional provinces, bringing all southern Vietnam under French colonial rule. Along with this new colony that they called Cochinchina, the French divided Vietnam into two additional regions: the protectorates of Annam (central Vietnam) and Tonkin (northern Vietnam).

Besides extracting raw materials and establishing a monopoly on the trade of salt, opium, and alcohol, plantations were another vehicle to fatten Paris’ coffers. In addition to the classic colonial crops of pepper, sugar cane, and rubber (the Michelin company would establish its own rubber plantation near Saigon), coffee was indispensable. Across Tonkin, Cochinchina, and in smaller parts of Annam, French-owned plantations appeared. Arabica was the first to be cultivated. It is suggested that the majority of Arabica grown by French planters originated from Réunion Island, from where a small quantity of seeds was imported in 1887.30

It was on Réunion, then called Bourbon, that the very first Arabica trees from Yemen were planted in 1715, and only one survived. This single tree became the genetic ancestor of all Bourbon coffee. 31 If the history of Arabica is that of a genetic bottleneck, the beginning of Arabica in Vietnam represents perhaps an even tighter chokepoint.

The first coffee plantations were established in Tonkin, where, as anyone who has visited northern Vietnam would surely know, the soil, climates and weather patterns were less than ideal for coffee growing. After much trial and error, only a few planters succeeded in the North, notably the brothers Ernest and Marius Borel. Meanwhile, the temperate climate of Cochinchina and the fertile volcanic plateau of Annam proved to be more suitable for coffee growing. Multiple varieties of Arabica were introduced to Vietnam towards the end of 19th and early 20th Century, with French planters experimenting and tinkering with seeds imported from as far as Java, Tahiti, Brazil and even Ethiopia.32

At the height of his coffee empire, Marius Borel boasted six plantations, extending to 2,000 hectares. Apart from the classic Bourbon, Borel identified additional varieties such as Grande Bourbon, Bourbon Rond, and Bourbon Le Roy (otherwise known as Laurina, a specialty coffee’s obsession). Other species existed, such as the recently rediscovered wild-grown Stenophylla. Of these Stenophylla plants, originally from the Nunez River in Eastern Guinea, Borel dismissed: “sa propagation n’est pas à recommander” —their propagation is not recommended—due to virtually nonexistent yield.33

But in Vietnam, Arabica did not popularize due to immense obstacles in the form of H. vastatrix, various root molds, and multiple types of borer (the most serious was white stem coffee borer Xylotrechus quadripes). These obstacles, coupled with low elevations and erratic weather, meant that while Arabica trudged on, it never reached the spectacular success of Sri Lanka or Brazil. Some planters started to plant another species alongside Arabica, testing its potential. In fact, Marius Borel confirmed that Liberica were grown alongside Arabica very early on.34 In 1907, Eugène Jung reported that the Director of Agriculture of Cochinchina specifically pointed out “grain products, Java peanuts, cotton, sugar cane, jute, indigo, cocoa, mulberry, coconut, copra, Liberian coffee and pepper” as promising crops in Indochina, signifying an early understanding of the potential of this species for the colony.35

Indeed, the trees were not attacked by borers (to Borel, a bigger threat to his coffee than H. vastatrix) and were resistant to leaf rust, but proved considerably worse at withstanding the cold of Northern Vietnam. In January 1893, Borel reported, 6,000 Liberica trees in Mr. Guillaume’s plantation “Cressonnière” lost their leaves after a sudden cold spell that plunged the temperature to 5°C. The trees recovered until 1897 when another cold snap turned all the cherries black before they ripened. In 1900, right before harvest time in February, another cold period wiped out the leaves along with the fruits, leaving Cressonnière Liberica quarters decimated.36 The coffee planters in Tonkin agreed that Liberica was not suitable for this region’s extreme temperature, and that it was reckless to propagate and encourage future planters to experiment with this species.

It was Excelsa that seemed to solve all the problems both Arabica and Liberica were facing. Discovered in 1903 during a mission to Lake Chari region of Chad, a group of French scientist-explorers collected, amongst others, wild coffee plants along their routes, while making observations on how coffee was cultivated in French Equatorial Guinea, Belgian Congo, and French Congo (note that this region is in Central Africa; whereas Liberica was strictly found along the continent’s Western coastline).37 Writing from the field to the audience of Revue des Cultures Coloniales, Auguste Chevalier could not contain his excitement. In the short dispatch, he announced that the mission had discovered three new Coffea species: Coffea congensis, Coffea silvatica, and Coffea excelsa.38 He marvelled at Excelsa’s heights (between 6 to 20 metres tall), its morphological diversity (leaf sizes ranging between 18 to 28 centimetres long; but not all trees were equally fruitful). Excelsa trees were found growing by the river banks, at elevations between 500 and 800 metres, making this species a potential candidate for lowland cultivation. Chevalier later observed that Excelsa could thrive in the equatorial heat and withstand cold plunges to below 10°C; its natural habitat in Central Africa had a distinct dry season of six months, and in the rainy season, rainfall could reach one metre. Excelsa, it seemed, was made to be cultivated in a large area across the French empire of similar climates and weather patterns.

A prime candidate? Vietnam.

The French empire’s agricultural network quickly sprung into action. Chevalier collected Excelsa seeds and distributed them. (Due to its geographical origin, Excelsa was also commonly called Chari). He sent a few seeds to Philippe de Vilmorin, a famous French botanist and plant collector. (Philippe is a part of the Vilmorin family, a family of celebrated horticulturalists and seed merchants). In 1905, Vilmorin sent Marius Borel ten dried fruits in their pulp. Marius asked his brother, Ernest Borel, to take care of these exotic seeds. From the dried fruits, 14 seeds were suitable for sowing, ten of them germinated, and nine trees survived. Planted in 1906, these trees bore their first harvests in 1910, producing 30 kg of cherries.39 The Borel brothers agreed that while the bark and leaves of Excelsa resembled those of Liberica, there were some notable differences. Excelsa leaves were softer, larger, and always green. The hottest days of summer and coldest days of winter seemed to have no effect on them; in fact, Excelsa seedlings would thrive under full sun, requiring virtually no shade. After seven years of experimenting with Excelsa, Marius Borel reported in 1913 that there was “no disease of any kind, no trace of attack by the dreaded Borer.” 14 years later, reflecting on his decades of coffee cultivation, Borel was equally, if not more, enthusiastic.40 “This is the future of coffee plantations in Tonkin,”41 he wrote, citing the trees’ resilience in both extreme heat (an advantage over Arabica) and intense cold (better than Robusta and Liberica), their ability to withstand hot wind (Laotian wind) in Northern Annam, their vigor against diseases and pests (very rarely were these trees attacked by H. vastatrix or Borer), and their developed roots that allowed the trees to go without fertilisers or watering for several years. The cherries had thinner pulp than Liberica, making processing and drying them more manageable. In fact, even now, we still observe all of these advantages that Borel noticed 100 years ago.

To planters in Tonkin and Java (Excelsa was first introduced to the Banglelan Experimental Station and Tjikeuments garden), this miracle species had one major weakness: its polymorphy. Similar to every other coffee species (with the exception of Arabica), Excelsa is allogamous, meaning it requires two parents to flower and produce seeds. Each seed, therefore, possesses inherent genetic diversity, which translates into a plethora of phenotypes. The legendary Dutch botanist Pieter. J. S. Cramer observed that variability is evident in Excelsa in almost all botanical characteristics. Reporting from Java, Cramer noted that in a small plantation, leaves could range from 20cm to 40cm in length, while their shapes were different from tree to tree. Cherry sizes could range between 1.5 to 2cm, and the ratio between cherries and green beans obtained after processing could vary greatly, between 9 to 1 up to 4.5 to 1.42 This is the reality our team still encounters and tries to work around today. There is nothing like observing and marveling at the diverse bounties of nature when you find yourself in an Excelca region. Within that fascinating cornucopia, however, lies the riddle 96B team has been trying to solve: how do we produce consistent and consistently good Excelsa? How do we understand these various phenotypes, and what can we do to figure out the most suitable cultivar?

We did not realize that our work on identifying and cultivating Excelsa was in line with what Cramer did in Java and what several planters tested in Tonkin more than a century ago. At Bangelan, Cramer set up his own experiments to obtain more stable and resistant varieties; the descendants of Lot 26 in his experimental garden, being the most stable and uniform, were distributed to farmers in Java possibly as early as 1914. Meanwhile, in Tonkin, various plantation owners started to import new seed batches from Bangelan, Tjikeumen, and Madagascar, taking note of the trees’ morphological traits to determine the best cultivar.43

Liberica and Excelsa gained traction due to the inherent weakness and vulnerability of Arabica. While the taste and prices of these species could not match the best Arabica of their day, their potential of heat and disease resistance made them legitimate contenders in a coffee belt ravaged by coffee leaf rust.

Just as suddenly as these coffees appeared, however, they rapidly went into decline. Liberica was the first to lose traction. The jubilation attached with the new Liberica plantation in Ceylon in mid-1870s was soon followed by dejection: within ten years, these vigorous trees had succumbed to the rust. According to McCook, Liberica started to fall victim to H. vastatrix in India in 1887 and then in British Malaya in 1894.44 In the Dutch East Indies, where Liberica had been planted with gusto in the 1880s and 1890s, the trees started to show signs of rust at the onset of the new century. In this climate, Cramer reported that new seeds from Liberia, Nigeria, and Dutch Guiana (nowadays Suriname) were imported to replace the troubled plants. These plants had prospered in their native lands, but became susceptible to the rust once settled in Java. Has Liberica degenerated? To find out, Cramer sent seeds from diseased Liberica trees back to their native Dutch Guiana, where H. vastatrix did not exist, and they prospered. The coffee, concluded the indefatigable scientist, had not become weaker; it was the rust that had adapted itself to the newly introduced species.45 So virulent were the rust strains in Java that subsequent species, including Excelsa, introduced to the island were observed to be resistant, but not immune. In contrast, as Liberica gradually lost its lustre in Vietnam, Excelsa continued to be cited as a beacon of hope (This is not evidence that Excelsa is “better”; It could well be that the rust strains in Java were simply much stronger than those in Vietnam).

The Liberica/Excelsa experiment was interrupted when a new species burst onto the scene. Documented around 1870 in Congo and described by Louis Pierre in 1895, Coffea canephora had the two necessary attributes for it to become a rapidly commoditised crop: productivity and rust resistance. First grown in 1900 in Java, it took awhile for planters and scientists to notice the potential of Canephora (commonly called Robusta, a name propagated by the Belgian Horticole Coloniale, mainly because the plants were, well, robust). But as the trees’ continued resistance to H. vastatrix and undeniable superior yield became apparent, mass cultivation followed. By the 1930s, most coffees on Java and Sumatra were Robusta.46 Liberica and Excelsa were essentially abandoned. From Java, Cramer lamented the premature death of the Excelsa experiment in his letter to Chevalier in 1926: “Excelsa . . . doesn’t have the place it deserves. If Robusta hadn’t come a little before the Excelsa, the latter would have gained a better foothold.”47

In Tonkin, Cochinchina, and Annam, Robusta slowly started to enjoy similar success. Planters and the colonial government saw great potential in growing Robusta alongside Excelsa, while keeping pockets of Arabica alive, where possible. This scenario could have continued had it not been for a force even more devastating than the rust: war. It is impossible to summarise all the conflicts that took place in Vietnam in the 20th century, especially during the period from the invasion of Japanese forces in 1940 to the unification in 1975. But one could return to the story of Poilane’s plantation with which this story commenced, to begin to imagine what could have taken place within and beyond coffee lands.

For the Poilane family, that fateful day of January 22, 1968, was not the end. They would take refuge in Hue and in Da Nang, crammed like sardines in tiny shelters with other civilians while the Tet Offensive continued. When the siege of Khe Sanh ended, Félix would leave his family and board Air Force C-130 mission 603 on the afternoon of April 13 to check on the plantation. The plane would go out of control, its right wing catching fire, which soon spread to the interior of the aircraft. The only civilian on board, Félix Poilane, died. On June 22, Madeleine and her children left Vietnam, never to return.

As the history of Excelsa unfolded, I could imagine a scenario in which Eugène Poilane, in contact with Auguste Chevalier, heard about Excelsa directly from the famous botanist. He could have visited one of the many coffee plantations owned by the Borel brothers, where he obtained the first nine seeds of Excelsa to start his own plantation in Khe Sanh. I also realised that there is a very high chance the Excelsa beans our team have been cultivating, processing, exporting, roasting, and drinking are the descendants of Poilane’s plantations. If so, it means that the coffee we interact with every day has a direct relationship to the Excelsa groves Chevalier and his colleagues came across near Lake Chari in 1903. It is a very real possibility, one that always touches me deeply. Whenever someone asks, why Liberica and Excelsa? I always hesitate to answer, because a short response never feels adequate. This piece is my attempt to begin to explain why.

In November 2025, I found myself getting ready for an European coffee tour, during which I would cup 96B’s 2025 Excelsa crops with roasters, baristas, and anyone interested in alternative coffee species. My last stop would be Paris. By then I had been digging deeply into the history of Liberica and Excelsa for a long time, and Poilane was a familiar name, often popping up in my research.

After a bit of digging, a few messages and a call later, I was able to reach Jean-Marie Poilane, the son of Madeleine and Félix Poilane. He was a child of five when he and his family left Vietnam. Fifty-seven years later, he was now my mother’s age.

It was raining on my last day in Paris. I dragged my luggage to The Beans on Fire on rue d’Aubervilliers, where I would give my final presentation and cupping session. It was there I met Jean-Marie in real life. We hugged and talked; and I simply could not convey into words my gratitude for his family, and my immense sadness for what happened.

But at last: 99 years after Eugène Poilane sowed those nine coffee seeds, his grandson got to try Chari for the first time.

I would like to thank Dr. Aaron Davis(Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew), Dr. Stuart McCook(University of Guelph), Jean-Marie Poilane, and Christopher Feran for the conversations, inspiration, comments and feedback.

Sourced cited

1 Dougan, C., & Weiss, S. (1983). Nineteen Sixty-Eight (The Vietnam Experience). Boston Publishing Company. p. 44.

2 Poilane, M. (1988) Ma vie au Vietnam. (unpublished memoir). All the details regarding the Poilane family, otherwise credited, are adapted from her memoir.

3 Prados, J., & Stubbe, R. W. (1991). Valley of Decision: the Siege of Khe Sanh. Naval Institute Press, p. 297.

4 Ward, C. J., & Burns, K. (2020). The Vietnam War. Vintage, p. 349.

5 Prados, J., & Stubbe, R. W. (1991), p. 25.

6 Tardieu-Blot. (1964). Eugène Poilane 1888-1964. Adansonia, 4(3), 351–354, p. 351.

7 Burgos, A., & Carré, B. (2021). Vie et œuvre d’Eugène Poilane (1888-1964). Revue D’ethnoécologie, 20. The details of Eugène’s life and work are adapted from Burgos & Carré’s paper.

8 A detail Jean-Marie Poilane shares.

9 This detail stands out in Madeleine Poilane’s memoir.

10 On her own, Bourdeauducq shot 47 tigers, not for fun, but to protect the plantation, its workers, and her family.

11 Tardieu-Blot. (1964), p. 353.

12 Prados, J., & Stubbe, R. W. (1991), p. 25.

13 Madeleine Poilane noted that in a typical year, they would harvest around 20 tons of Chari and 3 to 4 tons of Robusta.

14 Davis, A. P., Kiwuka, C., Faruk, A., Walubiri, M. J., & Kalema, J. (2022). The re-emergence of Liberica coffee as a major crop plant.

Nature Plants, 8, 1–7.

15 Davis, A. P., A Shepherd-Clowes, Cheek, M., Moat, J., Luo, D. W., C Kiwuka, J Kalema, B Tchiengué, & J Viruel. (2025). Genomic data define species delimitation in Liberica coffee with implications for crop development and conservation. Nature Plants, 11, 1729–1738.

16 Sanghera, S. (2024). Empireworld. Public Affairs.

17 McCook, S. (2014). Ephemeral Plantations: The Rise and Fall of Liberian Coffee, 1870-1900. In Comparing apples, oranges, and cotton: Environmental histories of the global plantation (pp. 85–112).

18 McCook, S. (2014).

19 Davis, A. P., et al. (2022).

20 Morris. E. (1868). An Address Before the Liberia Union Agricultural Enterprise Co. Philadelphia: WM. S. Young, Book & Job Printer.

21 McCook, S. (2019). Coffee Is Not Forever: A Global History of the Coffee Leaf Rust. (L.A. James & Jr. Webb,Eds.). Ohio University Press, p.36. This book provides invaluable information on coffee leaf rust and how farmers coped with this disease.

22 Cruwell G. A. (1878). Liberian Coffee in Ceylon: The History of the Introduction and Progress of the Cultivation Up to April 1878. Colombo: A.M. & J. Ferguson.

23 Bull, W. A. (1874). A Retail List of New, Beautiful and Rare Plants, offered by William Bull. London.

24 McCook, S. (2014), p. 95.

25 Morris, D. (1881). Notes on Liberian Coffee, Its History and Cultivation. Kingston, Jamaica: Government Printing Establishment, p. 2.

26 Cruwell G. A. (1878), p. xvi.

27 McCook, S. (2019), p. 48.

28 Ferguson A.M. & Ferguson J. (1882). The Tropical Agriculturist. Colombo, Ceylon.

29 McCook, S. (2014).

30 Borel, M. (1913). La Culture du Caféier au Tonkin. Hanoi-Haiphong.

31 Kornman, C. (2020). Bourbon’s Botanical Origins And The Evolution Of Laurina. Roast Magazine, 101, 33-48 .

32 The Agricultural Report of Annam for the Year 1929 (Rapport Agricole de L’Annam pour L’Année 1929) reported various experimental stations in Annam with Arabica, Excelsa, Robusta, and Liberica seedlings imported from various gardens and colonial territories.

33 Borel, M. (1913), p. 90.

34 Borel, M. (1913), p. 87.

35 Jung, E. L’Avenir Économique de Nos Colonies: Indo-Chine – Afrique Occidentale – Congo – Madagascar. Paris, p. 117.

36 Borel, M. (1913), p. 88.

37 Meanwhile, Dutch botanists found and named Coffea dewevrei in 1899. C. dewevrei and C. excelsa, as of now, are considered one species. See Davis, A. P., et al. (2022) for more detail.

38 Chevalier, A. (1903). Notes Préliminaires sur Quelques Caféiers Sauvages Nouveaux ou Peu Connus de L’Afrique Centrale. In Revue des Cultures Coloniales, 124.

39 Borel, M. (1913), p. 96.

40 Borel, M. (1927). Réflexions d’un Grand Planteur de Caféiers. In Journal D’Agriculture Traditionnelle et de Botanique Appliquée, 65 (pp. 5-10).

41 Borel, M. (1927), p. 7.

42 Pasquier R. (1926). La Culture du Caféier Excelsa à Java et en Indochine. In Journal D’Agriculture Traditionnelle et de Botanique Appliquée, 55, pp. 136-144.

43 Pasquier R. (1926).

44 McCook, S. (2019), p. 84.

45 Cramer, P. J. S. (1957). A Review of Literature of Coffee Research in Indonesia. Miscellaneous Publications Series, no. 15. Turrialba: SIC Editorial, Inter-American Institute of Agricultural Sciences.

46 McCook, S. (2019), p. 101.

47 Chevalier, A. (1926). Nouveaux documents sur le Caféier Chari (Suite et fin). In Revue de botanique appliquée et d’agriculture coloniale, 6e année, bulletin n°64, décembre 1926. pp. 765-772, p. 771.