My head hurts, my legs ache, I’m thirsty. For everything else it is, Ethiopia isn’t an easy place to travel—not how we do it, anyway.

We drive into Jimma, five of us packed into a Land Cruiser, a vehicle that is as much a symbol of success as a way of saying, “I need no roads, I make my own way.” The parade of coffee-colored skin and blue Soviet-made cars and goats and sheep flanks us, asserting its claim over the medians in a cacophonous symphony of thousand-decibel Amharic and bleating car horns. We’ve been on the road for twelve hours after driving for days, returning from Bensa, Adado, Hambela, Uraga, Limu and Agaro where we’d spent a week visiting coffee farms and processing stations.

Jimma’s people glow in the sun. As we pass, I feel their eyes upon us, staring at the uncommon spectacle of American forenjis passing through their corner of the universe. The collision of our Westernness and this place which served as the Genesis for all of humanity climaxes in cries of, “You, you, you!” and “I love you!” and “white man!” and whatever other English words the locals know.

But still: this place remains. In spite of all attempts at imperial or economic colonialism—by the Italians, the Soviets, the Chinese, the Americans, the UN, us—Ethiopia isn’t Africa: Ethiopia is Ethiopia. The birthplace of humanity, the birthplace of coffee.

From the wreckage of this cultural collision, I emerge from the car. I wear the earth like airbag dust on my skin and clothes, stained a hue of tangerine and rusting metal.

Ethiopia is an improbable nation. The only African country to escape true colonial rule. The place where coffee was born. The home to Lucy and humanity’s ancestry. The fastest-growing economy in Africa and yet a country where electricity isn’t ubiquitous. A Chinese-built railroad cuts through heart of Addis, and thousands of white foreigners come every year to buy coffee or sell Christianity or trade in the memory of Bob Marley—but here, in this place where humanity and coffee both began, I find myself on this particular night in December 2022, in the back of a truck, contemplating this history.

Sections

Introduction

Timeline of key events in Ethiopia

The ECX

Technoserve

Harrar & khat

Forest preservation

Washed process changes

Agronomic issues

2017 proclamation and dwindling exports

Covid-19 and civil war

A country in transition

Potential for quality

The future

Key developments:

1974 – The Derg overthrows Haile Selassie

1976 – Private land ownership abolished

1991 – Overthrow of the Derg; beginning of EPRDF governance

1995 – Ethiopian constitution affirms nationalized ownership of land

1999 – Creation of cooperative unions

2008 – Ethiopian Commodity Exchange established

2009 – Technoserve begins its work in Ethiopia coffee sector

2010 – UNESCO biome preserve declaration of Ethiopian forests

2013 – USAID begins Feed the Future program

2015 – Keta Meduga Union founded

2016 – Funding ends for Technoserve’s coffee project around Jimma

2017 – Government proclamation creating direct export market; 15% devaluation of the birr

2018 – Aby Ahmed elected as Prime Minister

2020 – Covid-19; beginning of the Tigray War; first Ethiopian Cup of Excellence

2021 – Global container shortage; Beginning of foreign currency shortage; FTFVCA ends

2022 – End of hostilities in Tigray war

2023 – Cup of Excellence suspended; the present day

Ever since I published my piece on the apparent decline of Kenyan coffee’s quality, I’ve heard from many readers—many of whom asked me my thoughts about Ethiopia.

It’s not a piece I’d hurry to write: since my first visit to Ethiopia in 2014, its export regulations have changed more times than the prime minister. News from Ethiopia doesn’t tend to make it onto American news broadcasts; Internet blackouts, language barriers, and a lack of rural cellular service keeps local news in Ethiopia local to Ethiopia. It’s an insular nation—by tradition and as a means for self-preservation—and I find it difficult to explain its majesty and complexity to anyone who hasn’t had the privilege of experiencing it.

Of coffee producing nations, Ethiopia is the fourth or fifth largest exporter of Arabica in the world with 4.7 million total bags exported in 2020-2021, less than only Brazil, Colombia and Indonesia. Unmatched in the genetic diversity of its plantings, strength of its traditions and with elevations higher than 2,000 meters scattered across every growing region, Ethiopia’s mystique as a producing country is matched only by its historical tendency toward quality. Even mediocre coffee from Ethiopia is regarded by specialty buyers more highly than some of the best coffees from other places on earth.

And yet: many buyers, roasters and baristas noted over the last two or three harvests that quality, in general, seemed lower than in previous years.

The first time I ever fell in love with a coffee, it was from Ethiopia: a washed coffee from the Yirgacheffe region that I drank by the liter in the corner of my college town’s local indie coffee shop, spilling words on page after page of would become my thesis. A year later, when I started working as a barista and roasting on a popcorn popper I found buried in my parents’ basement, it was a natural processed coffee from Sidama that made me understand that coffee could taste like something other than “brown water.” If you polled 10 current or former coffee professionals who worked in the industry when I was writing my Yirgacheffe-fueled thesis back in 2008, I’d put money on the fact that 8 or 9 of them would say that the most memorable coffee they had or the one that caused their specialty awakening was a coffee from Ethiopia.

Blueberry-bombs from Harrar and honeyed bergamot-jasmine coffees from the South defined a generation of specialty coffee professionals.

Where have all those coffees gone?

The very same year that I was writing my thesis and exchanging the water in my blood with coffee from Yirgacheffe, the Ethiopian government upended the entire industry, creating the Ethiopia Commodity Exchange (ECX) to “protect the rights and benefits of sellers, buyers, intermediaries, and the general public.” While previously, private exporters were able to purchase and process cherry at washing and drying stations that they owned, coffee now virtually exclusively passed through the ECX en route to export—with the exception of coffee sold through state-owned estates under investment licenses, and cooperative unions, which were first created by the government in 1999 “to manage coffee export business on behalf of primary coffee cooperatives that lacked human resources and logistic capacity.”

A farmer who grew coffee—or someone who collected cherry from his neighbors—could, under that system, only sell coffee to the exchange or to private washing stations, who would process that coffee (either into dried cherry and parchment) and then sell it to the exchange. Once delivered to ECX, it would be aggregated—stripped of its identifying information—and scored using the Q system and designated by region and grade. Under the ECX system, natural coffees would be classified Grades 3 through 9 (with the exception of specialty naturals from the South, which could be 1-2), while washed coffees would be classified as Grade 1 or Grade 2 based on defects and appearance as well as cup quality. A regional profile with a subtype indicated by a letter, A, or B, would be assessed based on the cup profile and how well it fit the designated regions—so a coffee that tasted like jasmine and lemon, for example, might be declared a Yirgacheffe A even if it were from Sidama. After that, coffees would receive a quality grade—Q1, Q2, or Grade 3—depending on its cup score. Coffees would be bundled into 30 bag contracts and sold to buyers based upon the regional profile and score—with a buyer not tasting the coffee until it was purchased. [The Boot Coffee export guide to Ethiopia has exquisite detail on ECX, if you’re interested]

ECX was efficient; by bundling coffee into contracts based on its quality and regional type, the price of coffee across Ethiopia remained relatively stable even as the rest of the world faced massive volatility during the roya and price crisis that began later that year. Qualities, too, were normalized as the aggregation process was managed by ECX labs, ensuring that every lot came attached to a score, grade, and cup profile. 2008, though, was also the Glory Days of the Third Wave: by then, the words “direct trade” had seeped into the marketing lexicon and roasters and buyers looked for ways to engage more directly with suppliers as well as achieve traceability on the coffees they purchased, and the general consuming public began to recognize the individual names of farms or coffee growers. And payment was quick: growers delivered cherry and received payment, on the spot.

The ECX system was designed for efficiency and volume of export—not traceability or separation—and by stripping the provenance of a coffee at the time of its entry into the system, limited the amount of information available about a coffee. While you might, if you knew the tagging system and tracking delivery of coffees to ECX warehouses be able to identify that an ECX lot came from one of a hundred specific washing stations in Kochere, you wouldn’t be able to identify the kebele where the cherry originated from, for example, the specific collection center, or any of the individual producer contributions (or how they were paid)—and with smallholders in Ethiopia farming, on average, less than 2 hectares of coffee, a single lot of coffee passing through ECX could contain coffee from hundreds if not thousands of producers.

ECX made coffee consistent, predictable, knowable and stable in quality—but increased its opacity with a commoditizing brush.

Other large-scale buyers required certified Organic or Fair Trade lots, which the ECX also was not equipped to handle; for those coffees, buyers only had one option to purchase their coffee, through unions that were legally organized as exporters and that could purchase coffee from member cooperatives established to collect and process cherry.

And so it was that beginning in 2008, coffee buyers looking to purchase coffee from Ethiopia—regardless of their quality requirements—had to buy from private exporters who, in turn, bought coffee from ECX, or purchase from unions.

By 2009, even as Ethiopia’s share of the global coffee market fell to its lowest ever share, the total monetary value of those exports reached a record high.

It didn’t take long for things to start to change—change that was perhaps precipitated by or a consequence of NGOs and third party actors looking to utilize the legal mechanisms of ECX for the economic betterment of producers as well as conservation of natural resources.

One of those actors—Technoserve (TNS)—came to Ethiopia in 2009, part of a string of projects coming through “Purchase for Progress,” an initiative of the UN World Food Program, and one funded by the Gates Foundation. Technoserve, which emblazons its website with the declarative “business solutions to poverty,” set its initial focus in Ethiopia on its coffee sector with a goal of “integrating smallholder coffee farmers into commercial markets.” Approximately 4 million smallholders in Ethiopia grow more than 95% of the country’s coffee—but with ECX in the way, Technoserve would have to find a way to connect those smallholders with specialty buyers.

During my first visit to Ethiopia in 2014, I met Carl Cervone (then of TNS and later co-founder of Enveritas) at TNS’ offices in Jimma. He explained the work that Technoserve’s team—which included quality experts, agronomists, technicians, sustainability experts, and administrative personnel—had been doing.

Through the ECX system, quality tiers were tied not only to cup score and defects, but also to process. Under the country’s export laws, anything assigned Grade 4 or higher through ECX was of exportable grade and must legally be exported; it could not be sold for domestic roasting and consumption. This meant, of course, that because washed coffees in this system always received a grade of 2 or higher, a washed coffee would automatically be rendered export-grade. In other words, merely by pulping coffee and washing off its mucilage before drying, a coffee that previously may have been sold domestically as a Djimma 5 might suddenly be exportable as a Grade 1 or Grade 2 washed coffee and fetch significantly higher prices.

And that’s the peculiarity of the ECX system that Technoserve gamed in pursuit of its objectives.

While washing stations dotted Yirgacheffe like sprouting grass and cooperative unions like the Sidama Union had existed for years, producers in the West where Technoserve operated—Agaro, Jimma, and Gera—still produced coffee through the traditional methods and delivered cherry primarily to ECX purchasing points. By organizing producers into cooperatives; financing the construction of washing stations with Colombian-made Penagos eco-pulpers and raised beds; and providing the cooperatives with training and technical support, Technoserve immediately improved the economic condition of smallholders in the West—and, as a consequence, birthed cooperatives that would go on to be name brands, famous for the quality of their washed coffees which they sold semi-exclusively to third wave icons like Stumptown and 49th Parallel: Biftu Gudina and Duromina.

Where only lower grade naturals existed before, Technoserve established a new standard for quality and cup profile in Ethiopia.

Technoserve was successful: they built 63 new washing stations in the West and 123 total across the country, organizing cooperatives around new regions outside of the traditional Jimma or Limu designations and bringing full traceability to coffees aggregated, processed and exported through these supply chains—in spite of structural deficiencies within export regulations. They established functional, quality-motivated cooperatives around principles that buyers wanted, and buyers responded: by the end of the project, Technoserve’s Coffee Initiative touched over 160,000 smallholders in Ethiopia, improving incomes by, on average, 21%.

But cooperatives—no matter how well run—were still hampered by bureaucracy under the ECX set of rules; unable to obtain an export license themselves, they still needed to affiliate with a Union or other service provider to export their coffee and receive the best possible price. Technoserve provided avenues for some coffee from some cooperatives to export through aligned service providers, ensuring more money flowed back to members, but for the remainder of the coffee produced by the cooperative—as well as for certifications like Organic and Fair Trade—cooperatives still must remain members of Unions.

Like ECX, this structure preserved a buffer layer in between growers, cooperatives and buyers, limiting direct and transparent contact between producer and buyer, and it incentivized volume: volume not just in terms of encouraging cooperatives to grow and purchase additional cherry (which would result in quality decreasing), but also in terms of growing a union’s total exports by increasing the number of cooperatives within that union.

At its peak, the Oromia Union, the first union formed, represented over 400 cooperatives on the order of eight times more cooperatives than the next largest union, the Sidama Union.

Size, of course, often breeds bureaucratic inefficiency in pursuit of cost efficiency. In the case of the Limu Union, many of the new Technoserve cooperatives felt as though their interests weren’t being well represented; they believed that they could achieve more favorable prices, faster ship times (and thus, a faster second payment to members), and greater security through year-over-year relationships if they formed their own union.

So: when Technoserve’s project in Western Ethiopia ended, in 2016, they did: they left the Limu Union to join the newly-formed Keta Meduga Union, led by a former Technoserve technician.

Meanwhile, out in the Northeast, in Harrar, coffee exports dwindled.

While oral tradition holds that the first domesticated coffee plant came from Harrar, and while dry processed coffee from Harrar was renowned for its intensely blueberry cup, it turned out to be the lesser important plant from the region—at least for the people who live there and grow it.

The story of coffee, of course, is inextricably linked to its psychoactive properties, even from its mythological genesis: in the origin story of coffee, Kaldi the goat herder found his missing goats “dancing” after consuming the flesh of a fruit growing on a tree he’d never noticed before. He tasted the fruit himself and, invigorated by its properties, ran home to his village to tell the elders about his discovery [where this alleged incident happened is the subject of some controversy, regional identity and contention. I tend to favor the story of Arabica’s origins being in Kaffa—but only because I’ve visited the site and believe coffee from Kaffa is wildly underrated].

Sufi monasteries drove coffee’s use and acceptance when monks discovered that coffee could keep them awake and alert for prayer. Coffee quickly spread throughout the Middle East, Asia, and Europe, aided by the allure of not only its aroma but also its stimulating quality as an accomplice to devotion. Banned then unbanned by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and Ottoman Empire and regarded (at least initially) with suspicion by the Catholic Church and much of the European aristocratic and ruling class, coffee became the drug of choice for much of society—a title it still holds claim to today.

In Colombia, Peru and across Latin America, the conflict between growers, processors and traffickers of coca and the United States government (and between leftist politicians and the United States government) led to decades of U.S. entanglements and government-sponsored violence, consolidating control of land, mills and export to favored parties while attempting to incentivize producers of coca to switch to coffee. In Yunnan, a region better known for tea, the provincial government, with support from Nestlé, sought to replace opium poppies primarily grown by Yunnan’s ethnic minorities with coffee—a model for “Alternative Development” playing out in Thailand today.

Khat, an evergreen shrub which contains the alkaloid cathinone in its leaves, which are chewed for its stimulant effect, has a cultural and social history in Ethiopia dating back millennia. Before ECX or Technoserve and before Starbucks was called Starbucks, economists had already observed the threat that khat posed to coffee production in Harrar. In a publication in Economic Botany from 1973, two analysts observed that, “Although chat was originally used exclusively by Moslems, its use now pervades all religions and socio-economic groups.”

The cooperative managers of the Agala Sekala Cooperative taking a break to chew khat, the bunch of leaves held by the second man from the left. Photo taken during my visit to Ethiopia in 2014.

As coffee prices remained stagnant in the early 2000s—prior to ECX—farmers began to replace coffee with khat. Khat, it turned out, was “worth more per acre than any other crop in the country, including coffee.”

As told by Jemal Moussa, a 45-year old khat farmer and father of six, “Coffee comes only once a year. But you can harvest khat twice a year. Khat is much more useful.” Unlike coffee, which only has one harvest per year, declines in production each season, and traded against a volatile market, khat offered liquidity and economic security, and sold for significantly more than coffee on a kilogram basis. “The [sale] price for 1kg of coffee is 31 birr, while for 1kg of khat it is 900 birr,” Heleanna Georgalis, the President of Moplaco Trading, told Perfect Daily Grind.

By 2015, even after ECX’s attempted interventions, “the land area used for Khat plantation was 44% of that used for coffee cultivation due to a volatile coffee market.” With forest cover declining—understood to be essential for coffee quality—and climate-related droughts impacting coffee production across the country, khat looked increasingly attractive.

“The coffee is still green on the tree—it needs rain to turn red. We are hoping it comes soon,” Aman Adinew of Metad told Reuters. “But if this trend continues, it is going to adversely impact the farmers and businessmen like us the growers like us and the country.”

Khat appeared to be a better solution for farmers increasingly facing food scarcity. Because it offered greater resilience to climate change, is easier to grow and harvest, and offered faster, more frequent payment, much of the coffeelands—from Yemen to Harrar—was replanted with khat.

By that time, the government realized it had a different problem: Ethiopia’s forests were disappearing.

During the late 19th century, before invaders set their eyes on Ethiopia, or the west called Ethiopia “Ethiopia”, and before the brutal conquests of Menelik II formed boundaries that became the country’s borders, about 30% of Ethiopia was covered by forests. Coffea arabica, native only to Ethiopia, evolved within those forests—likely in Kaffa, a region named after the former Kingdom of Kaffa which for centuries has depended upon harvesting of coffee as a main source of income.

With pressures mounting from fungus and disease and climate change, the genetic diversity of coffee from Ethiopia—thousands of varieties, some still unknown and undiscovered, all descended from wild coffee trees in Kaffa that grow as thin wisps climbing upward to find light in the canopy of dense, ancient forests—offers one of the greatest hopes for the survival of the species.

But today, only about 3% of Kaffa’s forests remain—with 60% of those losses occurring within the last 30 years.

And so, in 2010, UNESCO recognized the forests around Kaffa as a Biosphere Reserve as part of the Man and the Biosphere Programme, prompting the Ethiopian government to move swiftly to find ways to protect the remaining forestlands. In just the two decades preceding UESCO’s recognition of Kaffa, Ethiopia had “lost 18.6% of its forest cover, or around 2,818,000 ha,” at a rate of nearly 1% per year.

Justification for protecting the Kaffa’s montane forests is easy: “Ethiopia’s forests contain 219 million metric tons of carbon in living forest biomass,” as well as:

some 1408 known species of amphibians, birds, mammals and reptiles according to figures from the World Conservation Monitoring Centre. Of these, 7.0% are endemic, meaning they exist in no other country, and 4.6% are threatened. Ethiopia is home to at least 6603 species of vascular plants, of which 15.1% are endemic. 4.9% of Ethiopia is protected under IUCN categories I-V.

And it’s the deep end of coffee’s gene pool—a cash crop that is responsible for 10% of Ethiopia’s GDP. “Uncontrolled deforestation is eroding this important genetic pool of coffee,” noted one 2015 study from University of Huddersfield, driven by “expansion of agricultural land, small and large scale coffee cultivation, tea plantations and unsustainable wood extraction.”

For centuries, the people of Kaffa had used its forests for economic purposes, trading in coffee, civet oil, coriander, and ivory, with land usage dictated by generational inheritance and historical stewardship. Every year, when the fruit on wild coffee trees would begin to ripen, the steward of those lands would trudge deep into the forest to collect and dry the cherries. Following the UNESCO declaration, because of this historical usage and in pursuit of conservation, Ethiopia imposed a nationwide policy of Participatory Forest Management (PFM), with a regulated list of approved products. Participatory Forest Management, “by engaging local communities in the management of forests is believed to increase economic and environmental benefits while reducing costs of conservation”:

[Participatory Forest Management] aims to develop partnership between government and local communities in forest resource management; the government is expected to play more of facilitation and overall monitoring role. It develops local institutions (bylaws and community based organizations) to fill the institutional vacuum at the grassroots and to develop sustainable forest-based livelihood options.

Source

The notion of using the land for commercial means—the cultivation of coffee—as a forest management and conservation tactic wasn’t new: by the time ECX was introduced, about 35 Sub-Saharan countries practiced some form of participatory land management. “The underlying premise of PFM is that sustainable forest management is most likely to occur when local communities develop a sense of ownership, assume the responsibility of managing local forests and are incentivized for their engagement.” In Ethiopia, PFM was predicated upon the fact that forest coffee systems resulted in higher yields (thus economic advantage) compared with wild coffee cultivation, but unlike semi-forested systems (which produced even higher yields), “low management intensity in forest coffee systems does not modify natural species composition.” So: PFM model coffee forest systems would be more profitable, but less destructive.

Meanwhile, unmanaged forests—like those traditionally used by the people of Kaffa—would be at risk of deforestation because “increasing demand for wood is likely to cause over-exploitation of some highly valued secondary forest and climax tree species.”

The strategy made sense: “Due to the carbon retained in trees, shrubs and soils, agroforestry has potential to offset greenhouse gas emissions from conversion to more intensive forms of land use, particularly in the case of traditional coffee farming.”

But to gain the economic benefits associated, the government would have to convert areas of traditional/wild coffee cultivation to managed use.

The tractor.

During my first visit to Ethiopia in 2014, we drove to Kaffa to visit a forest coffee farm and got stopped on the roads outside Bonga after dark. We’d taken a tractor and mules to get to our host’s farm, with the roads washed out from the region’s heavy rains, and were accompanied by guards. During the 2km journey from the main road to the farm, night had fallen. Earlier in the day, on our 8 hour drive from Jimma, our host told us that there had been skirmishes in Kaffa recently—something related to land disputes, and locals feeling they’d been cheated—but assured us that the land his family farmed on, a large estate of some 100 hectares, was obtained legally and lawfully.

Of course.

The backstory he gave was something along the lines of, “Well, there were people on the land before us. They’d been living here for years, collecting cherries from the trees, and then the land stopped producing. It was no longer worth anything to them, so they gave up their lands and left. Now that it’s producing again, they think they have a right to return even though the land is ours.”

I didn’t buy it—and hours later, staring at the men blocking our exit wielding spears and kalashnikovs, something didn’t add up.

One of the quirks of the Ethiopian system is that, technically, all land is owned by the government. The Derg—the military junta that overthrew Emperor Haile Salassie in 1974—issued a land reform program intended to destroy the feudal system by nationalizing all of Ethiopia’s land. Private property was abolished; coffee plantations once owned by foreigners or feudal lords were confiscated and redistributed.

Resettlement of land and villagization was a priority for the Derg as a way to address the “overpopulation” of the Ethiopian highlands. The resettlement program ran until 1988, and as written by Gebru Tareke in Ethiopian Revolution, “Between 1984 and 1986, 594,190 people were hastily, forcibly, and pitilessly uprooted from the cool, dry highlands of Shewa, Tigray, and Wello to the hot, wet lowlands of Gojjam, Illubabor, Kafa and Wellega.” Even after the overthrow of the Derg in 1991 by the Ethiopian Peoples Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), the central principle of land reform remained in force: the Ethiopian constitution adopted in 1995 vests ownership of the land “in the State and in the peoples of Ethiopia.” Leases for up to 99 years may be obtained from the government, but unlike in the Western legal tradition, right to use does not imply private property or ownership.

In other words, no one person owns the forests: the government does. And the government can redistribute rights to their usage as it sees fit.

While the government stripped private exporters of their ability to own processing stations and collect cherry when the ECX system was established, they left one loophole: operators of state-owned farms greater than 100 hectares in size with long term leases of 99 years could obtain development licenses to export directly.

In pursuit of conservation and to incentivize it through capitalistic means the government undertook a campaign of land dispossession in conjunction with a voluntary resettlement campaign to encourage people to move from less productive areas to more productive areas. This was tantamount to eviction with condemnation to a life in agriculture rather than industry; meanwhile, the government took lands traditionally held, worked and stewarded to consolidate them into 100 hectare plots and lease them to private corporations for the purpose of coffee cultivation.

This led to large exporters—from Tracon to Metad to Mullege—leasing large plots of land from the government so that they could grow, process, and export directly—all while bypassing ECX, and regardless of who might traditionally use those lands.

And so tenure insecurity—already an issue in Ethiopia—was exacerbated by government interventions taken in pursuit of conservation. Tensions over land tenancy rose, with unrest beginning in 2014 following the introduction of the Addis Ababa Master Plan growing into violent clashes and mass protests in Addis Ababa.

In response, a young Parliamentarian member of the Oromo Democratic Party representing the kebele of Gomma in Agaro, Abiy Ahmed, made opposition to land-grabbing the central focus of his politics.

Sometime between my 2016 visit to Ethiopia and my next in 2019, the ground shifted.

Qualities seemed to have fallen across the board. In Limu, I’d noticed the natural I’d been buying for years was less vibrant and started to show a hollow, nutty slight vegetal character; in Agaro, cup scores from the most famous of the Keta Meduga Union cooperatives declined, and the coffees showed up less complex, less aromatic and with creeping notes of paper and fade. In the South, wet mills in places that for years were renowned for quality—Kochere, Reko, Hambela—delivered coffee that was just a memory of what it once was.

When coffees did land—even if they did land on time—quality was like flash powder. They’d land with moisture contents north of 12%—while I’d become accustomed to Ethiopian coffee arriving with moisture in the 9% range (or even in the high 8s) and highly resistant to fade.

Allegedly bombastic blueberry or jasmine-and-bergamot cups went quiet.

When Technoserve finished its project in Western Ethiopia in 2016 after the Gates Foundation funding ran dry, the cooperatives it helped to establish, finance and train were fully self-governing. Cooperative management turned their attention to delivering value to members in the form of a second payment derived from the cooperative’s profits that year—profits that resulted directly from the sale of coffee. By increasing the volume of cherry they purchased, processed and sold, cooperatives could increase their profitability.

Duromina, for example, one of the darlings of Keta Meduga which I’d first visited in 2014 and which Stumptown catapulted to third wave infamy, had grown from 75 members producing two containers of coffee to 327 members producing eighteen. To grow volume that substantially, the cooperative needed to purchase cherry from outside of its membership. Sorting and selective picking suffered; and without optimal ripeness, potential quality declined.

Increased volumes of cherry created bottlenecks in processing. Duromina began to push its pulper, a Technoserve-standard Penagos ecopulper, faster and faster—pulping 2,500kg of cherry per hour, at the limit of its capacity and higher than the recommended 1,500. Once pulped, the next bottleneck was in drying: instead of drying to a stable moisture content of 9.5-10% which might take 8 or 9 days, coffees were moved from the bed when they reached 12.

Nearby, at Biftu Gudina—another cooperative I’d first visited in 2014—they found additional ways to handle volume by purchasing an additional pulper. Instead of an expensive Penagos ecopulper preferred by Technoserve, Biftu Gudina opted for an Estrada—a large, chromed-out pulper that would look at home parked next to a flying car on the set of a cheesy 1950s sci-fi. Both pulpers, however, allow for a calibration setting that ultimately determines how much of the mucilage the machine removes. Overtime, they’d increased the amount of mucilage the machines removed; by 2019 the machines were set to complete removal.

By removing mucilage mechanically rather than via fermentation and washing, Biftu Gudina could turn over their fermentation tanks more rapidly, increasing the capacity of the wet mill to process a massive influx of cherry. The cooperative reduced the time the coffee spent in the fermentation tanks to just ~6 hours, down from the 10, 12 or 16 I’d seen previously. While mechanically demucilaged coffee can be of exceptional quality, it’s also not particularly stable, resulting in more rapid flavor deterioration. Further, it skips fermentation, a step which is known to improve the sensory character of coffee.

By 2019, in order to grow their production volumes, most of the cooperatives I visited in the West employed the same tactics: collecting more cherry with looser sorting requirements; pulping it faster while removing 80-100% of the mucilage; fermenting less; and drying their coffee in full sun in 4-6 days to just 12-12.5% moisture content.

But the strategy they’d pursued—producing more coffee in the hopes of selling it at high prices through the union to deliver a dividend to members—didn’t go according to plan. In the tension between quality and volume, volume won; and when quality lost, specialty buyers didn’t show.

During the 2016-2017 harvest, Duromina produced 16 containers. Of those, the Union sold 14. The remaining two were sold—at significantly lower prices—to the local market. The following year, they produced 18; only 12 sold through the Union.

Out in Limu, the trees looked stressed. Leafless branches draped listlessly from thin trunks of coffee trees growing beneath forests that looked like they belonged on some moon of Endor. Production was down; quality was down. The land at these estates—planted with coffee, in most cases, a decade earlier, seemed to be giving up.

Its buyers were, too.

In many countries, the government’s official coffee agriculture board provides recommendations for how often to stump or replace coffee trees in an effort to keep production and, thus, exports stable or increasing. In Colombia, for example, the recommendation provided by FNC is 7 years; a new tree might only bear fruit and give a harvest after 4 or 5 years, but a stumped tree will regrow faster and provide fruit in 2-3 years with the benefit of established roots and vigorous production from new growth. In Ethiopia, the standard practice is to stump trees every 10-15 years. Pruning, if it’s done at all, is quite limited and typically just includes “topping,” or removal of the vertically growing wood of the main trunk to limit the tree’s growth upward. While in general, older trees will produce fruit of excellent quality, yields overall will be lower; branch dieback occurs often in conjunction with a lower leaf-to-fruit ratio, exacerbating issues of production stability through a resulting biennial cycle of production.

A productive and quality-driven managed forest coffee farm in Limu. Photo taken during my 2016 visit.

The forest coffee farms in Limu—and coffee gardens across Ethiopia—had some distinct quality advantages to begin with which would mitigate or fortify perceived reductions in quality or reductions in yield, much in the way that particulate pollution can offset the effects of global warming. It’s well established that, broadly speaking, coffees grown under shade are correlated with higher cup quality. In Ethiopia, coffee evolved under the forest canopies of Gera, Limu and Kaffa. As the government sought to promote agricultural preservation of the forests through participatory land management and 99 year leases, they incentivized increasing production. Intensive farming in an agroforestry style—such as the removal of competing species, thinning of shade, and selection of coffee, shade and other plants—can increase yields.

Without commensurate management of the soil and application of amendments and inputs, however, gradually, over time, the soil will become depleted; when the soil is depleted, the trees become less fruitful, the trees’ vulnerability to weather, pest and disease increases, and quality decreases.

It’s something I’ve seen all over the world but nowhere as acutely as Ethiopia, a country where 95% of coffee is produced by some 4 million smallholders. In a USAID report summarizing their Feed the Future’s Value Chain Activity (FTFVCA) program published in October 2017, the agency noted that in Ethiopia, “Production has been stagnating for the past eight years with yields flat because improved input use is very low, and less than 5 percent of producers use fertilizer or pesticides.” If inputs are used at all, they typically consist almost exclusively of composted cascara and other plant materials, without amending the balance of macro- or micro-nutrients.

While yields for a young tree might be 8-12 kg of cherry per tree per harvest, under these conditions, within 5-10 years, production may plummet to as low as 5 kg. Cup scores, too, will fall.

Climate change also impacted potential qualities—an effect which would be exacerbated by removal of shade canopy and soil depletion. Moata Raya, a Q-grader and co-founder of CoQua Lab in Ethiopia who works as the agent for Crop to Cup in Ethiopia, studied agronomy at Jimma University before working as a technician for Technoserve, where he helped to establish many of the most famous Keta Meduga cooperatives. As we walked through a 10-year old farm planted at 2,300 meters, Moata told me that when he was in university twenty years ago, it was taught that “coffee does not grow above 2,000 meters.” In her 2006 thesis, University of Passau PhD candidate Christine B. Schmitt observed that “Wild coffee grows throughout the forest until 2,050 masl except for extremely shaded and humid sites.” Climate change, which has already impacted rainfall in Ethiopia and increased temperatures by 0.3ºC per decade, threatens the production of coffee, a delicate tree which prefers temperatures below 22º. A 2012 study in Nature examining the threat of climate change to coffee production observed that by moving coffee to more suitable, cooler, high elevation land, coffee farmers could adapt to these changing conditions.

Across Ethiopia, the areas buyers once flocked to before moving on all exhibited the same pattern: exceptional quality for 5-10 years, followed by a decline. It seems like every few years, there’s a new part of Ethiopia that attracts specialty buyers like mosquitos hunting for flesh, propelled by the never-ending quest for quality. While we used to clamor for coffees from Kochere or Hambela or Agaro, they’d had their moment—and that moment had gone, moved to another woreda or another region with younger trees and higher elevations.

All of the coffee I’d purchased from Ethiopia ahead of my 2019 visit came through the three export channels permitted after the establishment of ECX:

- Coffee collected and processed by cooperatives and exported by Unions (only cooperatives could export through this channel);

- Coffee collected and processed by private processing stations sold to ECX, then purchased by private exporters from ECX for export (A private exporter could not own washing stations); and

- Coffee grown, processed and self-exported by these estates in Keffa and Limu that leased land from the government for 99 years and held an investment license (farmers that held investment licenses could export only coffee grown on their land).

At the time, the only way to purchase coffee “direct” from a producer was to buy from the third channel, those farmers operating under a development license from the government—larger estates operated by wealthier businessmen, growing coffee on land that wasn’t traditionally theirs. It’s complicated: by eschewing traceability in its structure in exchange for stability of price and quality (both of which it did well, and efficiently), ECX drove specialty buyers outside of its own system to achieve fully transparent supply chains, occasionally at the detriment of smallholders. Technoserve built fully transparent supply chains within the structure, enabling roasters to access cooperatives with greater traceability than before—but ultimately, those contracts were sold and exported through the machinery and bureaucratic pace of the Unions.

To meet the modern moment, in 2017, the government issued a proclamation liberalizing the coffee market—radically transforming the coffee market of the country and creating a total of five export channels:

- Private Exporters: While before exporters could only purchase coffee from ECX, following the proclamation they could once again own and operate their own washing stations and direct export the coffee they processed (bypassing ECX). They were also permitted to trade vertically with suppliers such as other washing stations and dry mill owners;

- Supplier-Exporters: If a washing station or dry mill owner fulfilled the requirements to export, they could be permitted to export coffee. Prior to 2017, these suppliers could purchase cherry and process it, but would have to sell that coffee to ECX for export.

- Cooperatives: Rather than needing to export through a Union or sell to ECX, as they had before, cooperatives that fulfilled the government requirements could now obtain export licenses and export directly to buyers;

- Smallholders: Farmers with a minimum of 2 hectares of land could obtain licenses to export directly; and

- Growers: Coffee growers could purchase cherry from their neighbors and export coffee from these outgrowers.

By allowing smallholders and washing stations to obtain export licenses—a modernization of the export industry that would allow buyers to have direct, traceable, and transparent relationships with producers and/or processors—the government eventually effectively rendered ECX obsolete. But because smallholders lacked infrastructure for processing, financing to purchase cherry or wait for payment, or access to buyers, even if they did obtain licenses to export, most smallholders continued to sell their cherry the old ways for immediate payment in the years immediately following the full implementation of the proclamation in 2019.

Owners of private washing stations, able to once again export the coffee they collected and processed directly, could negotiate with buyers; Buyers could contract coffees from specific collections and specific processes from specific washing stations and negotiate prices directly—so long as those prices were above a minimum legal export price established by the government.

Farmer-exporters under development licenses, who previously had been restricted from exporting any coffee they didn’t grow, could, under the proclamation, engage in cherry collection and processing of coffee from their neighbors for export—creating new pathways for coffees to reach export outside of ECX or cooperatives. For the owners of large estates—like those I’d visited in the forests of Kaffa and Limu and Gera who received development licenses by signing 99-year leases aimed at protecting Ethiopia’s remaining montane forests through agricultural uses—this meant that they no longer needed to purchase coffee from ECX; they could buy cherry from their “outgrowers,” at significantly lower prices, process and export it.

They could grow their volumes of production and export—even as their own harvests waned.

This, in fact, was the government’s primary motivation for reform: bolstering exports. Coffee is Ethiopia’s most important cash crop and, in terms of sheer percentage, accounts for approximately 40% of all of Ethiopian exports. Agriculture in total is around 40% of GDP and contributes employment for 80% of the population. In Ethiopia, a tension between export and domestic consumption exists; while other countries may consume the coffee they produce, it’s nowhere near at the levels of Ethiopia. Unlike many coffee producing countries, coffee consumption is central to Ethiopian culture and tradition. While domestic consumption in Colombia, for example, accounts for just under 17% of total production, in Ethiopia, domestic consumption accounts for over 50%.

The entire context of Ethiopian coffee—from the establishment of the ECX to the participation of NGOs like Technoserve—can be understood through the lens of coffee export. By mandating that all washed coffees must legally be exported and barring roasters in Ethiopia from selling specialty grades under the law, the government hoped to create channels for coffee export that could not cross-pollinate into domestic supplies.

But even with these measures implemented, as production increased, consumption followed suit, and exports continued to decrease:

Coffee production in Ethiopia has grown steadily over the past three years and, with suitable growing conditions, is forecasted to reach to 7.62 million bags (457,200 MT) in 2021/22. 50-55% of Ethiopia’s production is consumed domestically. Local consumption is estimated to increase to 3.55 million bags in MY 2020/21. Ethiopia is the largest coffee exporter in the region and its shipments are primarily green coffee. In 2019, the country enacted a new marketing and export policy to allow direct coffee exports by smallholders with minimum of two hectares of land and by commercial farms in order to encourage vertical integration and improve coffee traceability. Exports from October 2019 to September 2020 reached to 4.135 million bags (248,129 MT), 2326 MT lower than MY 2018/19.

source

The Ethiopian economy and the welfare of the country’s people are inherently impacted by this decline in coffee exports. Its contribution to GDP and revenues aside, coffee exports play a vital bidirectional economic function to Ethiopia through arbitrage and serving as a source for bringing foreign currency into the country’s central bank. Coffee is traded domestically in birr, but then purchased by buyers at time of export in USD—which is then used by importers on the international market to purchase goods from abroad for import into Ethiopia for sale. Ethiopia relies on foreign imports for foodstuffs, pharmaceuticals, fuels, machinery and fertilizers—and coffee, as Ethiopia’s largest export, serves as a financing vehicle for these imports.

Traditionally, large coffee exporters would not only sell coffee but would also operate import companies (Mullege, for example, imports diapers and hygiene products which they then sell to corner stores around the country); coffee export, rather than a profit center, exists for them as a way to generate USD for higher-margin import businesses. For this reason, many exporters are willing to sell coffee for export at a loss.

The power and stability of the USD relative to the birr makes the flow of USD into the economy, obtained through the export of coffee, essential. In 2017, when the proclamation was issued, the central bank of Ethiopia devalued the birr by 15% hoping to spur exports by making the country’s goods cheaper on the international market to increase the flow of USD into the economy. Declining coffee exports threatened to disrupt this foreign currency exchange, depriving the country not only of export revenues but also essential goods imported from China, India, the U.S. and the Middle East and paid for in USD.

Two years into his term, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed faced a crisis in Ethiopia.

In response to the Covid-19 pandemic, which first appeared in Ethiopia on March 13, 2020, the federal government imposed restrictions to control the spread of the virus—first closing down nightclubs in Addis and then, on March 23, closing land borders and deploying security forces to the borders to stop movement across them, including along the border of Eritrea, adjacent to Ethopia’s Tigray region in the country’s north. Internet blackouts, which Abiy implemented in January 2020 in reaction to rising tensions with the Oromo Liberation Army, expanded.

As a parliamentarian, Abiy gained popularity and rapidly ascended within the Oromo Democratic Party (ODP) after making himself a central figure in the fight against land-grabbing activities in Oromia stemming from the Addis Ababa Master Plan, a 2014 plan to expand the borders of Addis Ababa by resettling areas in Oromia.

Following three years of unrest, on February 15, 2018, Hailemariam Desalegn resigned as Prime Minister of Ethiopia as well as chairman of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). EPRDF, a coalition of four ethnically-based parties—ODP, Amhara Democratic Party (ADP), Southern Ethiopian People’s Democratic Movement (SEPDM) and Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF)—held the majority in Parliament, assuring that its chairman would be the next minister.

In a closed-door election on March 27, 2018, the leaders of the EPRDF elected Abiy Ahmed as Prime Minister over strong opposition from the TPLF.

In his acceptance speech following his confirmation, Abiy presented an optimistic vision for the future of Ethiopia built around unity and democratic ideals. “Taking lessons from our mistakes,” he declared, “we should work to bring about political stability, build a better and united Ethiopia.” He called for free and fair elections, pledged to combat corruption within the country, and expressed a desire to open talks with Eritrea to address ongoing tensions with the country following the end of the Eritrean-Ethiopian war nearly two decades earlier.

18 months later, Abiy succeeded on this last promise, helping to bring an end to two decades of conflict with Eritrea—an achievement for which he was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize. As part of the agreement Abiy forged with Eritrea, Ethiopia surrendered the border town of Badme in the Tigray region of Ethiopia to Eritrea, fulfilling the conditions laid out in the 2000 Algiers Agreement treaty and formally bringing about peace between the two nations. The TPLF, which had dominated national politics from 1991 until 2018, opposed the decision, citing “fundamental flaws” and objecting to Abiy’s failure to consult with TPLF or representatives of border regions that would be impacted by the decision.

The tension between Abiy and the TPLF grew when on December 1, 2019, Abiy merged the ethnic and region-based factions of the EPRDF into a new Prosperity Party under his leadership; TPLF refused to join the new coalition party, and, after being ousted from power, relocated the party to the Tigray region, administering local control.

On March 31, 2020, in response to the pandemic, the National Electoral Board of Ethiopia postponed the general elections scheduled to be held on August 29, 2020, resulting in parliament extending the terms of legislators and executive branch representatives beyond the constitutionally mandated term. In defiance to what they believed to be unconstitutional actions by the government, the TPLF held its own elections on September 9; the government, declaring Tigray’s elections to be illegal, slashed federal funding to the region, which TPLF decried as “tantamount to a declaration of war.” TPLF further declared that, because constitutional terms for the federal legislature, Council of Ministers, and prime minister expired on October 5, 2020, it considered “the incumbent” (Abiy) constitutionally illegitimate following that date. Abiy sent elite military units to Asmara, across the border from Tigray in Eritrea; in pre-emptive self-defense, Tigray Special Forces and TPLF aligned militia attacked the Ethiopian National Defense Force Northern Command headquarters, triggering a counter-offensive from the Ethiopian government, a complete suspension of government services to Tigray, and a civil war which would last two years, displacing nearly 3 million people resulting in over 875,000 refugees and as many as 800,000 deaths.

The United States and international community, in response to evidence of war crimes and widespread reports of sexual violence, genocide, and crimes against humanity committed by both sides of the conflict, wielded economic pressure and imposed sanctions on Ethiopia. With sanctions in place, the flow of foreign currency into the country’s economic system slowed—hampering the ability to import goods. Expenditures on military action, the destruction of infrastructure, and inability of the country to import critical foodstuffs and fertilizer led to rampant inflation.

Coffee, as a result, became even more valuable. International sanctions against Ethiopia did not prohibit the trade of coffee; thus, coffee exports would continue to be a source of securing USD in exchange for weakening birr. In a post-2017 proclamation Ethiopia, the ECX no longer centrally regulated exports—consequently, local prices for cherry no longer correlated with FOB prices but instead correlated only with an exporter’s willingness to pay. Since coffee export was a way for exporters to secure foreign currency in exchange for birr, they needed to collect, aggregate and process as much cherry as they could afford or otherwise finance. To stabilize the market and ensure a level playing field between ECX and private collectors, the Coffee & Tea Authority introduced a minimum export price in 2020, hoping to also bolster the value of that export internationally while staving off a race to the bottom.

A paradox of coffee production is that higher prices tend to lead to lower quality overall. Selective picking—necessary to produce the highest quality coffee—also necessarily reduces yields, reducing exports; reduced exports mean less foreign currency; less foreign currency means less liquidity and ability to purchase goods for import at competitive prices. Thus, as a need for increased exports increases, competition for cherry also increases—necessitating softening of requirements for cherry selection and a willingness to work beyond trusted or established networks of growers in order to collect greater volumes of cherry.

Quality can endure many trials; the crucible of war is not one of them. The theater of war combined with challenges posed by the ongoing covid-19 pandemic made domestic logistics difficult, slow and dangerous. Security around Addis Ababa, where the majority of coffee mills are located, compounded the difficulty and slowed exports past the normal timeline toward the fall, placing it on a direct collision course with the global container shortage crisis of 2021. During the worst of the crisis, Moata told me that he slept at the dry mill with coffees awaiting milling and export for Korea and the U.S. as a measure of security against theft—dried coffee, valuable as it was, became a target for thieves. With coffee increasingly dried rapidly and above stable moisture levels, and with delays in export leaving coffees exposed to hot and humid conditions at dry mills for extended periods, coffees exported in the 2020 and 2021 years inevitably arrived at its destination late end faded—if they arrived at all.

Writing down a processing protocol for a lactic anaerobic style fermentation for farmer-exporter Basha Bekele

In December 2022, I returned to Ethiopia for the first time since February 2019 and found the country in a state of transition.

By the time we arrived, the government had announced a ceasefire, a step toward bringing the Tigray War to a close. The effects of the 2017 proclamation rippled, and everywhere we traveled we met smallholders who within recent years received their own licenses to export. A project by USAID called Feed the Future, which provided smallholders with training, drying materials and assistance in securing export licenses, propelled this transformation further. And in 2020, Ethiopia held its first ever Cup of Excellence competition—sponsored by Feed the Future—with the winner, Nigussie Gemeda Mude, scoring over 90 points for a natural Sidama.

The future for Ethiopian specialty coffee seemed bright.

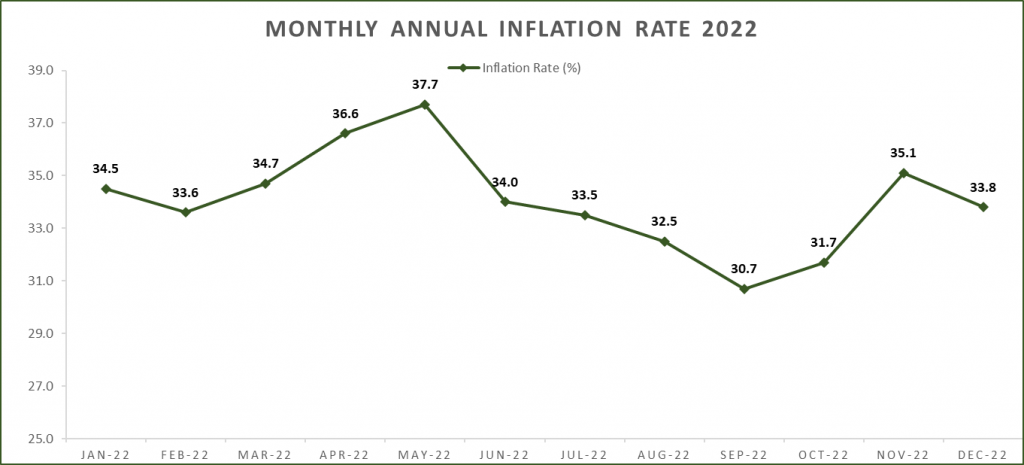

Tempering this optimism, though, was the economic context: the birr continued to weaken against the dollar, and cherry prices continued to rise. The foreign currency shortage, which began a year prior, accelerated in 2022. With less than two months of runway for essential imports, the central bank imposed measures to manage inflation—which hovered around 25% for over a year then spiked to 37.7% in 2022—and collect USD. To ensure that currency was available for the import of essential goods, the Ethiopian restricted the access of importers of non-essential goods to foreign currency, reduced the amount of foreign currency Ethiopian individuals may hold, reduced the amount of foreign currency that an exporter could retain in reserves for use in import activities from 70% to 30%, with the remainder legally required to be converted to birr within 30 days, and cracked down on the black market trade of foreign currency which kept USD out of the circulation of the banking system.

In previous years, the black market price for USD had been a small premium over bank rates; with supply low and demand high, in December, bank exchange rates for birr were between 52 and 53 birr per USD—and black market rates were around 95, hitting a high of 105 during the harvest.

Competition for cherry intensified, with large-scale exporters establishing new cherry collection sites and paying higher prices, driving up local prices. Exporters of other agricultural commodities like sesame who operated in the north but had operations disrupted because of the war switched to coffee—and flush with cash, drove up cherry prices further, with no quality control body in between purchase and export. For smallholders who sell ripe cherry, higher prices are advantageous; for processors of coffee such as the smallholders with export licenses I met in the South, where cherry prices were highest, they were a problem. Because cherry is purchased from producers at the time of delivery and paid in cash but money from a sale to export doesn’t arrive for as many as three or four months, processing enough cherry to justify export requires financing. With inflation and the cost of capital rising, there is a great financial risk for cherry collectors and processors in the period between harvest and export.

During my first visit to Ethiopia in 2014, I recorded cherry prices at recent highs of 13-16 birr per kg, a speculative and bullish price based on rumors of frost in Brazil that might create an opportunity for Ethiopian coffee. In Bensa, a region that, because of its elevation, could not support coffee cultivation in the highlands until two decades ago, the 2022 harvest began with cherry prices around 55-60 birr and by the midpoint reached 80-90 birr; the end of the season they’d reached 110 (prices in the West were much more affordable—a mere 45-55 birr per kg).

With an exchange rate of 53 birr per USD, a cherry price of 90 birr per kg cherry would mean that the green cost itself contributes $4.63 in costs toward the FOB price.

As the exchange rate worsened for Ethiopian coffee producers, so too did a cherry processor’s exposure. Rather than holding parchment and waiting for sale and currency exchange, they may be better off taking advantage of high prices and selling locally, or holding their coffee back from export in the hopes that the market would rise. And because of high prices locally, the illicit domestic trade of export-grade coffee flourished, with organized crime allegedly colluding with government officials in the enterprise.

Even with favorable exchange rates, elevated FOB prices relative to the movement of the C-market created a widening gap between prices for Ethiopian coffee and those for coffee from other places. High rejection of contracts from Europe as well as exporters holding onto coffee that they’d bought at high prices, hoping the market would climb higher compounded the challenges; stocks from the previous harvest had not yet depleted and the signals for the 2022-2023 harvest indicated that production would be high.

Finally, in January, the Coffee & Tea Authority, which sets a daily minimum registration price (FOB Djibouti) pulled the pressure relief valve and lowered export prices across Grade 2s, which had been trading nearly as high as Grade 1s, and Grades 4-5.

It was too little, too late; with prices high and importers frustrated about the quality of the 2021-2022 harvests, demand remained low.

But still: agronomic conditions were good. Potential for quality was good—if you were willing to pay for it.

Many new coffee farmers or coffee farmers engaged in speciality elsewhere in the country moved to regions that, before climate change, were previously unplantable, not known for coffee, or which were newly planted—like Bensa and Uraga. With soil that had never grown grain and cooler climates, these are the regions buyers look to for quality—a strategy apparently validated by the results of the 2021 Cup of Excellence.

In just three days in Bensa in December, I met 6 of the top 10 winners of CoE 2021.

And where quality grows, buyers seemed to follow; Buyers that absconded from lower elevation passé regions of Adado and Idido and Gedeb ascended with cup scores to the highlands of Guji, searching for the best coffees like a coffee buyer game of Pokémon Go.

Grower-exporters with direct access to buyers are becoming increasingly sophisticated to the specialty market, understanding which varieties of trees offer greater potential for quality and renovating their farms accordingly. In Bombe, a number of growers I spoke with mentioned replacing variety 74162 with a local landrace they called Walega (74158). Many began to take an interest in specialty coffee and coffee quality—a paradigm shift actualized in the opening of the first specialty coffee shop I’d ever seen in all of Ethiopia, in Hawassa (owned by the large exporter Daye Bensa).

Farmers worked collaboratively; the training and materials provided by the USAID Feed the Future program spread and combined with other processing-specific training from roasters and NGOs. At virtually every drying station I visited in the South and West, I saw blue barrels used for anaerobic style processes. Whereas before, coffee from Ethiopia was presented either as washed or natural, in 2023 we have access to honeys, anaerobic and lactic naturals, and various other boutique preparations [It’s not entirely new, though: I will note here out of pride that the first yeast inoculated fermentations ever conducted in Ethiopia were ones that I developed with a producer in Kaffa—back in 2018]. The diversity of processing styles and cup profiles available to buyers grew to match the genetic diversity of the trees.

Patio drying in the West

Still missing, of course, were the blueberry bombs. While before, a Grade 4 Sidama may have delivered these flavors reliably, with the change in collections and processing in recent years, that cup profile is less common than red-fruit cups or orange-citric-honey cups. Raised beds are ubiquitous across Ethiopia now, from smallholders to large processors; even where patio drying—the traditional practice in Harrar—still existed, savvy producers controlled the drying temperatures and rate to ensure stability. Shade—one of the components provided by the Feed the Future program—was something in use at some point in almost every drying station I saw, even if just for skin drying tables or placed over the raised beds at peak sun.

Particularly in years with disordered, disrupted shipping and export cycles, protecting the coffee from premature fade is valuable; drying using lower temperatures and higher airflow, like occurs with shade cover and raised beds, slows the drying process, reduces stress on the seed and helps to achieve this. But as a consequence of lower temperatures, slower drying, and uniform selection standards, coffees don’t taste like blueberry anymore. Sound processing techniques have changed the character we come to expect from coffee.

While researchers are only beginning to identify specific molecules responsible for fruity character in coffee, we can speculate: ethyl acetate, known to form during wine fermentations as a byproduct of acetic acid and ethanol, and 3-isopropyl-buyrate smell like blueberry in low concentrations. In a study of the microbial succession during dry coffee fermentations, researchers found that over the progression of a fermentation, the population modulates from being dominated by bacteria to being dominated by yeast as the coffee dries and water activity falls:

Included in the population were yeasts known to produce fruity esters like those responsible for blueberry as well as its precursors such as acetic acid:

Acetic acid was detected on the 2nd and 12th fermentation days, mainly in the pulp and mucilage fractions. Acetic acid production is an aerobic metabolic process that can be of bacterial origin or the product of the oxidation of yeast- produced ethanol. The bacteria present on the surface of coffee cherries produce this acid, which can then migrate to the pulp and mucilage, where it can interfere with the organoleptic quality of the beans.

In this paper, the phenomenon was studied over a 22 day drying period using cherry selected at a uniform ripeness; sun drying on patios in Ethiopia might happen as rapidly as 4-6 days and include both under ripe cherry (which would likely be removed at a dry mill in higher grades due to its lower density) as well as overripes (which would provide more sugar to drive fermentation). As a result of higher temperatures drying in this way, microbial activity would increase; this would accelerate the formation of acetic acid-producing bacteria and production of acetic acid at the beginning of the fermentation—risking the “ferment” defect—but rapid dehydration would rapidly modulate the fermentation toward yeasts known to produce blueberry character in co-ferments alongside Saccharomyces cerevisiae like Pichia anomala, particularly at temperatures typical of patio drying. In the 22 day study, these two yeasts didn’t appear until day 18, when water activity fell below 0.80; in a real world scenario on a patio, this might happen as rapidly as day 2 or 3.

In my estimation, this is a net gain; while the character of these coffees was remarkable and unmistakable, they were fickle: riskier to produce, short of shelf life, and the high note of an era when much of Ethiopia’s dry processed coffee was lower quality. Millers noted that producing these coffees resulted in a high number of lower grades and lower outturns; importers noted less uniformity and greater contract rejections; roasters noted how quickly these coffees faded into paper and astringency.

All that the rest of us noticed is that we don’t taste them as often anymore.

If you want these cup profiles, you can find them—buried deep in the forward offers of specialty importers or on the spot menus of gourmet importers that might carry Sidama Grade 4s. Ever-discerning specialty buyers abandoned these lower grades long ago like they left parts of Ethiopia, in search of higher qualities and fewer quakers—but to taste the coffee you remember, you need to buy the coffees you used to buy.

Cup them. You might be surprised.

Standing at the washing station at Layo Teraga Cooperative in Uraga, which, for the first time in 2022 left its union and obtained its own export license

The tension between modernity and tradition is one we struggle with in coffee—an existential quandary that demands we understand who we are, where we came from, and who we want to be.

Ethiopia, a country with a growing economy and one that was virtually unknown to outsiders until the 19th century lives in the space of this tension in an elegant juxtaposition: every day, millions of people in traditional dress stop in the afternoon to pan-roast, hand-pulverize and drink coffee adjacent to men in business suits taking lunch and connecting to the world via Telegram and Instagram on smartphones. It’s a world of split ideologies—two-thirds Christian and one-third Muslim—and one with as many as 86 languages spoken where a coffee grower from the West may not understand one from the South.

Ethiopia’s coffee market, too, lives in this place between worlds: only five years into its experiment of a transparent, direct export system, three of them during a global pandemic and two of them during civil war. The quality is there; but the winds must change. To confront the discordant reality the country faces—impressive qualities, yet declining exports—Ethiopia must continue to examine its foreign exchange and monetary policies which hamper the liquidity of smallholders and suppress the progress of this new type of exporter.

In 2023, raised beds fill the South and Penagos pulpers dot the west; gone are frequent blueberry notes, but so too is the inferior reputation of coffees produced in this traditional way. Producers are floating cherry, selectively picking and controlling their drying. In the 50 or so preship samples I’ve tasted, qualities are excellent—with scores routinely hitting 87 or 88 points and even the 86s outshining 86s from other places in distinctiveness. In the place of blueberry we have intense fruit notes ranging from strawberry to cherry to apricot (and truly yes, even blueberry is still there); sugary citrus ranging from tangerine to mango and pineapple; soaring bouquets of flowers from lavender to jasmine; chocolates, nuts, and spice (if you want it); and clean cup after clean cup after clean cup.

Anything you want from coffee, you can find it in Ethiopia.

But coffee from Ethiopia doesn’t have to taste the way we expect it to; Producers there are experimenting, exchanging and growing increasingly sophisticated in their methods. As the number of producers processing their own coffee increases in this brave new world of direct export, so too will the number of cup profiles emerging from Ethiopia. It’s self-determination in a way we haven’t seen before.

And Ethiopia—the place where coffee evolved and still grows wild in the last vestiges of montane forests across the West—is our last best hope of the species’ survival as the effects of climate change accelerate.

Tags: coffee ethiopia green coffee processing

Thanks a lot, Christopher.

Love it, you are the Best!

Thank you for all of your sage wisdom and lessons over the years, Moata, and for showing me Ethiopia 🙏

Incredible writing; elegant, erudite, exquisite. Thanks for this treat.

Thanks for taking the time!

I found this absolutely fascinating! Thank you so much for writing this!

Thanks so much for reading!

Excellent story

Thanks for reading!

This was awesome. As someone who is just starting to put the pieces together when it comes to coffee processing and sourcing it was rad to read a piece that echoes the lessons regarding processing effects I’ve learned during the current harvest in Mexico as well as the detailed macro economic lessons I picked up in college. On top of all of that, you offered some hints at how one can judge where a coffee will go flavor wise 6-12 months beyond what you might experience in a patio or pre-ship sample. Thank you for all of that.

This was a terrific read (and re-read), Christopher. Your research and perspective from multiple visits helps explain so much of what we have expereinced in the cup over the last 6-8 years. Boosts my confidence in what I thought was, in part, simply my aging palate.

Thanks a lot for these impressive insights on Ethiopian coffee and its challenges – plus a connection to politics and society. Great to find such detailed information delivered for free so I can continue learning and understanding about all this!

This is detailed, comprehensive and informative report!

Thanks for organizing and share it with us 👍👍

I really enjoyed this article Saturday morning being my bed, on the eve of Ethiopia Easter.

Thank you Christopher Feran, you explored the Ethiopian coffee at a glance from region to region and also reminded me the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus.

Great read, I haev learnt a lot about what stands out for Ethiopian coffee. Unfortunately you are mistaken about your summary of the the political environment. Tigrayan (TPLF) did not dominate the politics (4 parties ruled in coalition and all are responsible for the downfall of pre-Abiy government). Second they didn’t start the war. Please read the recently published book Understanding Ethiopia’s Tigray War. Read any western governmental texts about the war the war didn’t start when Tigrayan forces attacked the army base. We, Tigrayans, as a people were the primary targets of this war. this is a disservice in the least to the million Tigrayan Ethiopian with two three sentences. The war was a genocide.

Indeed, understanding the war requires significant depth and research—which goes beyond the scope of this piece’s intention. Ignoring it altogether would be a disservice; I instead chose to leave discussions about the conflict (which was still ongoing as I wrote this piece) to those with greater specialty. I did highlight the conflict and, indeed, the genocide. Thank you for reading and for your thoughtful reply.

I’m not sure where you obtain your knowledge, but this is a fantastic issue. I should spend some time understanding or learning more. Thank you for the amazing information; I needed this for my mission.

excellent story. I learned a lot!