Leadership is a privilege to better the lives of others. It is not an opportunity to satisfy personal greed.

Mwai Kibaki, third president of Kenya

In the weeks since I published my post on the coffee industry in Kenya, I’ve had conversations with countless coffee producers, agents, and exporters in Kenya as well as roasters and green buyers from around the world.

Through those conversations, I’ve learned a few things that felt worthy of including in a follow-up post.

How to get the actual coffee you thought you contracted

I’ve heard from a number of individuals both at export in Kenya and importers who work heavily in Kenya. One of them suggested that many buyers may be experiencing a phenomenon not unique to Kenya but certainly more common there: bait and switch.

Sometimes, a buyer will taste a coffee on a table—say a Gatomboya AA, for example (chosen arbitrarily)—and wish to purchase that lot. They may want to buy it, writing Gatomboya AA into the contract, only to discover at the arrival that the coffee doesn’t match their expectation.

That’s the catch: it may be a Gatomboya AA, but not the Gatomboya AA they wanted.

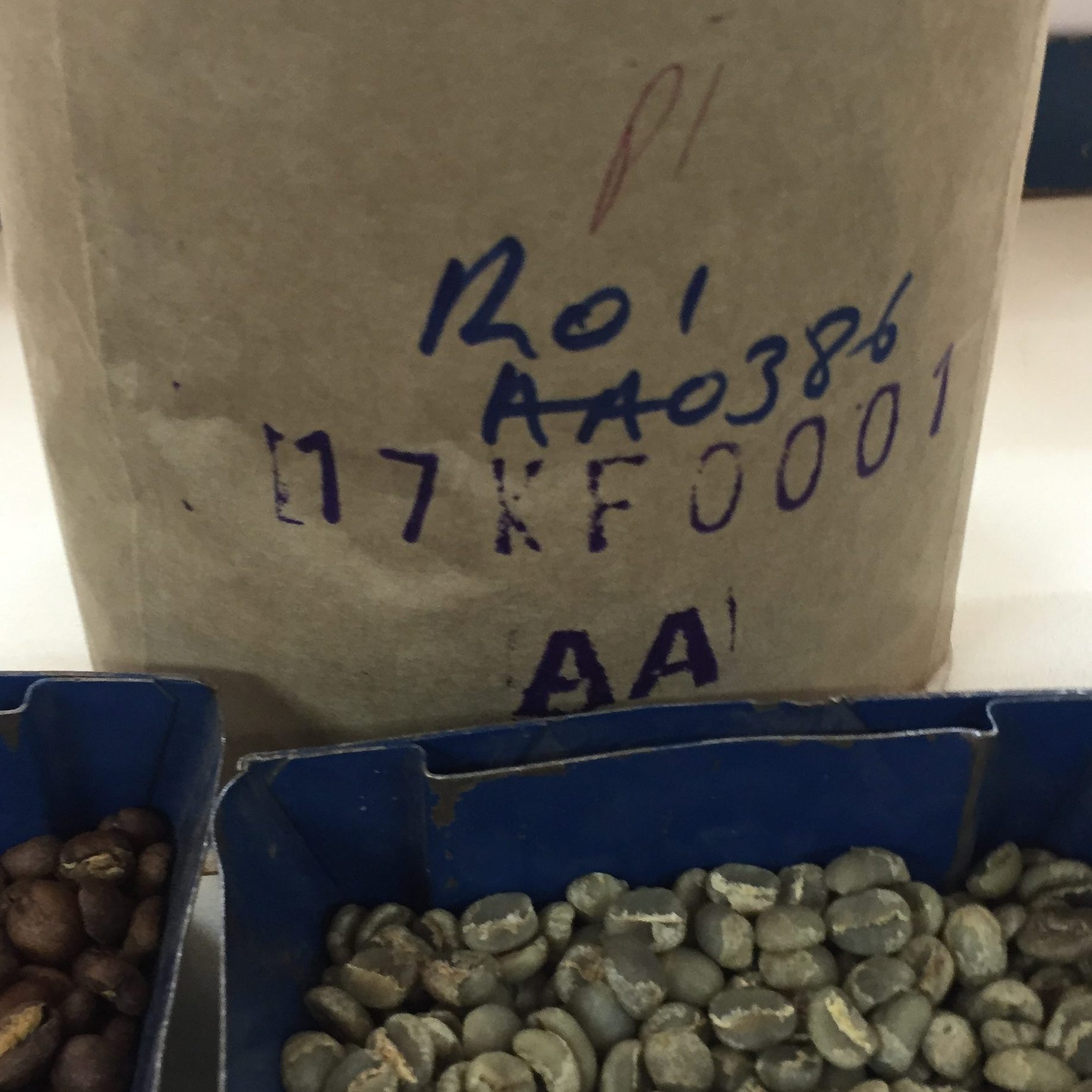

But by using a lot’s outturn number—a distinct number which is sewn on the inside of each bag and traceable through the entire Kenyan system—it’s possible to better work the Kenya export system to ensure the integrity and identity of a lot and prevent the coffee you want to contract from being sold to another party and substituted for a sample with a similar name.

An outturn number is structured as “00AA0000”, with the first two digits being the week of the year, from 1-52, beginning October 1; the second set of digits being the dry mill designation; and the third being the coffee batch of the day. This outturn number connects a batch to its sequence at a dry mill on a given day to ensure that, say, the Gatomboya AA you’re buying is in fact the very same lot that you tasted on the cupping table—from the very same dry milling. This number will also be tied to receipts from smallholders contributing to that lot since, of course, they still own the coffee up to the time of export—and haven’t yet been paid.

When you’re cupping coffee on a cupping table in Kenya, always ask for the out turn number of the lot on the table you want to buy, and contract that specific outturn number.

How to work directly with producers—if you have the scale

Stephen Vick kindly shared how his company has navigated the export system to buy directly from producers through a three-party contract, a mechanism that Klaus Thomsen from Coffee Collective separately informed me that he’s employed successfully as well. Stephen commented:

A cooperative or single state farm can sell their coffee directly with a Grower’s Marketers Export license. This is where things get tricky, however, as the cooperatives have to make an agreement with a marketing agent every year. So unless a roaster is able to buy ALL of the coffee from a particular cooperative or estate for the entire harvest year, the marketing agent will have to facilitate the sale. My company did purchase all of the coffee (all grades, everything) from one coop in 2018 and that presented some challenges, but that year the coop did not have to use a marketing agent at all. We picked the coffee up from the dry mill and deposited the money directly into the cooperative’s bank account. Now, we have an agreement with one of the marketing agents that their value add is transparent (3% I think) and we can still pay the cooperatives directly into their accounts for the lots we purchase directly. Lots of grey area here.

Where there’s hope in Kenyan coffee

Stephen, whose depth of experience both in the U.S. market and the Kenyan coffee industry is, in my estimation, unrivaled, showed up in the way I’d wanted: to inspire hope. He noted that while land values in central Kenya around Nairobi continue to skyrocket and make coffee cultivation increasingly untenable, areas in the West are the future of Kenyan specialty coffee, with younger producers who are motivated and excited about modern production practices and who are able to reinvest in their businesses.

Blood money

Though coffee production in Kenya began in the late 19th century, it wasn’t until Kenyan independence in 1963 that native Kenyans were able to fully legally cultivate coffee (the Cooperative Societies Ordinance of 1945 technically allowed it, but the industry remained in control of settlers until after the Mau Mau Uprising) —a fact I alluded to in my original post, but an important one that I neglected to call out directly.

When they ceded government control to the Kenyan people, the British retained economic advantage through the established power structures such as the Nairobi Coffee Exchange—which was established in 1934 under colonial British rule as a way to enhance the quality of Kenyan coffee and which, until 2006, was the only legal mechanism for coffee export in Kenya—and through the four export companies which dominated and continue to dominate exports. The system was intentionally established to disempower and disenfranchise Kenyan smallholders: That architecture remains to this day.

In recent years, however, there does seem to be progress toward reform and redistribution of economic power to smallholders—a march toward progress that has been matched by renewed vigor from industry and multinationals to prevent these reforms from being enacted so as to preserve the existing hegemonic structures.

The first two reforms from President Uhuru Kenyatta—Kenya’s Crops Coffee General Regulations of 2019 and CMA (Capital Markets Authority) Coffee Exchanges Regulations of 2020—build on Kenyatta’s General Regulation 2016 and work to improve the payment speed to farmers and modernize the supply chain and exchange system by digitizing the systems.

Two additional competing proposals, Coffee Bill 2020 (sponsored by the chairman of the Senate standing committee on Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries, Njeru Ndwiga) and Coffee Bill 2021 (developed by Agriculture CS Peter Munya without public input) are currently in reading and debate stages. Notably, Coffee Bill 2021 would consolidate regulatory authority of the coffee industry with Coffee Board of Kenya— a reversal of the 2016 reforms granting more power to governors (in response to the now-infamous standoff in Nyeri).

A task force established by President Kenyatta to examine and make recommendations for overhauling the entire coffee industry recommended increased direct sales of coffee from Kenya, a national minimum price for coffee, expedited payments to producers, and transforming the Nairobi Coffee Exchange into a public limited company. These recommendations were met with immediate opposition from governors, who would see their power and financial access weakened, and from industry: “The implementation of the task force report is expected to begin in the next few weeks and some players in the coffee industry feel that it is headed for disaster because it has focused on the farmer only rather than the entire industry.”

But of course—if we’re not primarily concerned about farmers and their welfare, then whose welfare should we be concerned with?

The 2019 Crops bill, another part of President Kenyatta’s strategy for reforming the sector, has, too, hit a roadblock: court injunctions resulting from a lawsuit filed by Kenyan governors who sought to annul the reform: “The National Government’s role in the constitution is strictly limited to policy while implementation of these policies and other agricultural function are a preserve of the County Governments.”

Industry—millers, marketing agents and foreign-owned multinationals—rather than accepting the need for reform in the face of the decline of Kenya’s coffee sector, have chosen to engage in a campaign of corruption and misinformation to prevent these progressive measures from being implemented.

A contact in Kenya provided me with three letters penned by “Concerned Coffee Farmers spread across the entire Country” detailing these efforts.

In the first letter, addressed to Martin Ngare of Coffee Management Services Ltd, accuses Dorman’s and CMS of engaging in the practice of acting both as a marketing agent (who must work on behalf of farmers for up to a 3% commission) and a buyer, a conflict of interest that is not legal under the 2019 reforms.

Further, the letter charges that Mr. Ngare “orchestrated and financed the Legal case Petition No. 181 of 2020….where you prayed to the courts to squash the 2019 Coffee Regulations” and openly accuses Mr. Ngare and CMS/Dorman’s of bribery: “we are reliably informed that there are attempts from you and your organisation to frustrate the coffee reform process through the Judiciary by unfairly incentivizing our Honorable Judges financially so as to rule against and nullify The Crops (Coffee) (General) Regulations, 2019 in the aforementioned Case Number E401 of 2021 lodged at the Nairobi Court of Appeal.”

These charges are outlined in the second letter, to Mr. Manyonge Wanyama:

We are aware of a plan by a section of Coffee value chain mainly Commercial Millers and Marketers to attempt frustrate the coffee reform process through our Honorable Courts by bribing our Honorable Judges financially so as to rule against The Crops (Coffee) (General) Regulations, 2019 and nullify them in the Case Number E401 of 2021 lodged at the Nairobi Court of Appeal through a Co-operative Society known as Rwama Farmers Co-operative Society and other cases that will be lodged in other High Courts. We are aware that the plans to have a case lodged in Meru High Courts is at an advanced stage and Justice Patrick is expected to rule against The Crops (Coffee) (General) Regulations, 2019, a ruling which will enable to Foreign owned Multinationals to continue oppressing and taking advantage of our labour.

In the third letter, the author of the letter addresses Justice Patrick J. Otieno, who presides over the case and was expected to rule against the 2019 Crops regulation, directly: “We raise to you that the money you will be given is coffee farmers money because these cartels will simply undervalue/underpay or exaggerate milling losses of our coffee to raise you and the judge’s bribe. DO NOT TAKE BLOOD MONEY!”

The letters are available to download, read, and share here: [1] [2] [3].

Tags: buying coffee corruption green coffee kenya outturns relationship

https://kenyanmarketintelligence.com/is-uhurus-toxic-jealous-brother-muhoho-kenyatta-staging-another-sportpesa-sting-operation-in-the-coffee-sector/

There are remarkable claims in here — If you have any of the documents referenced, I would be happy to publish them if I’m able to authenticate them. Please feel free to reach me securely via Telegram or Signal.

What is your opinion on the blockchain and on the guarantees it gives in terms of registration and non-intermediation? In your opinion, the blockchain incorporated into a digital platform where information and transactions are managed by producers, could it be a solution without intermediation?

Hey there, thanks for reading and for the comment. Blockchain is interesting to me as a potential tool for traceability through the value stream and I know some companies (like Sucafina) are putting a lot of money behind it. Security and information management concerns aside, I’ll remain on the sidelines and unconvinced, for the moment, until I see an example where blockchain not only delivers on its promise but also is scalable, accessible to smallholders in remote regions, and doesn’t constrict the number of exporters through which a producer can sell.

Thank you for your reply. I understand and partly share your perplexities.

I’ve been working on it for a few months, with SFCC (Slow Food Coffee Coalition) and with a blockchain app (Trusty) created and managed by a small Italian digital company (Apio srl). We think about your wavelength and I’ll keep you informed if you like. I am very interested in the future of coffee in Kenya, so I will be happy to follow your upgrades.