Don’t eat anything incapable of rotting.

Michael Pollan

I got a message from Kaapo Paavolainen of One Day Coffee on Telegram, I think, after he saw me snark on Jonathan Gagné’s Ad Astra channel about cinnamon and coffee. I personally don’t want cinnamon anywhere near a fermentation tank—but I also don’t believe it’s the role of (mostly white) competition judges or coffee buyers in consuming countries to dictate what is and is not acceptable processing practice. It hits a little too close to how “terroir” is a managed expectation imposed by buyers that is, ultimately, imperialistic in nature—but that’s a post for another time (A worthy moment for a refrain: let’s not conflate aesthetic choices with moral ones).

Kaapo had seen my stories on Instagram about ongoing work between Koichi Higuchi of the esteemed Higuchi Matsunosuke Shoten Co., a Japanese producer of koji spores; Jeremy Umansky of Larder; and me using koji as a way to manipulate the flavor of aging or so-called past crop green coffees. So far, the way that we’d done it—using extremely technical, difficult laboratory methods in Higuchi’s clean rooms to inoculate and grow different strains of koji on green coffee—generated unconventional and unusual cup profiles.

Unusual: I’m talking brothy, shoyu-miso-umami bombs, with kombucha-like aromatics, apparitions of acidity and decidedly uncoffeelike character.

But, Kaapo asked: could koji be used to produce what specialty roasters would deem to be a better cup? Could it improve processing in any way?

I thought it could—so I offered to collaborate and devised a series of processing protocols employing koji for Kaapo and his producing partners at El Vergel in Colombia that he could use as part of his presentation for WBC 2021 in Milan.

Non-intervention, a phenomenon in winemaking that somehow has managed to get rebranded into the more pristine-sounding ‘natural wine movement’ (don’t get me started on “natural processing” in coffee), wields a tremendous amount of privilege in its apparent reverence for nature, random-chance, and business models that require a high degree of experience, training, resources, skill or else remarkable luck to execute at scale.

Human societies aren’t built on “what might or might not happen” — human societies are built on observing, attempting to replicate, produce and optimize for preferable outcomes. Human societies are built around the notion of what is likely to happen and, at the heart of it, about influencing conditions toward those desirable outcomes.

There’s a certain beautiful interaction that happens: humans observe a phenomenon in nature, attempt to control nature, and nature adapts. Rinse and repeat.

Through this mechanism, we invented agriculture, livestock, sanitation, architecture and every other innovation that supports human civilization.

I’ve mentioned the staple crops of civilization in a previous post—but what I didn’t talk about is how nature reacted after humans domesticated those crops. In some ways, the results were cybernetic, global and cataclysmic, such as the theorized desertification caused by early humans in what is now the Sahara Desert. In others, they were microscopic—such as the adaptation and domestication of a filamentous fungus, a mold—Aspergillus oryzae—that resulted from humanity’s domestication of rice.

A. oryzae shares 99.5% of the genetic material with Aspergillus flavus, its ancestral species. Through a genetic mutation some 9,000 years ago made possible by humanity’s domestication of rice and the abundant evolutionary opportunity that resulted, a genetic switch flipped: A. flavus was no longer A. flavus and, rather than producing aflatoxin, the fuzzy mold growing on steamed riced produced aromas that one could describe as grapefruit and mango, saccharifying the grain’s starches through amylase enzyme and producing amino acids. Through repeated effort—and ample opportunity—humanity domesticated the mold that grew on domesticated rice, then bred, replicated and sold it through traditional methods passed down for generations in China and Japan. Today, koji is produced by just a small number of producers, many of whom have themselves been producing koji for generations—like Koichi-san and his family.

In coffee, we talk about tradition—but it’s nowhere near comparable to the temporal scale of koji. The entire story of koji’s domestication is foundational to the cultural organization and development of civilization in China and Japan—and the emergence of koji precedes human’s discovery of coffee by some nine or ten millennia.

Comparatively speaking, coffee—which has only been grown in the western hemisphere for a matter of centuries and in some countries for just a few generations—has traditions in the way that dogwood trees have roots. The rigidity with which we, as buyers in a consuming country, view certain expectations of provenance or profile based upon any notion of tradition is therefore, in context, pretty remarkable.

There are people alive who remember a time when coffee wasn’t grown in Mexico.

The traditions surrounding koji, though, have been practiced since before the Spanish language even existed—and millennia before Kaldi lost his mythical dancing goats in Ethiopia.

If in the timeline of human civilization, koji is old, coffee is new.

Koji fermentation is unique—rather than producing alcohol or carbon dioxide or organic acids, koji has the ability to transform its substrate differently than yeast or bacteria. Depending on the fermentation conditions, koji produces varying ratios of both amino acids like glutamate as well as amylase enzyme, which can saccharify the starches in something like rice, making them available for fermentation by yeast into sake. The ratios at which each metabolic byproduct is produced depends on the strain of koji as well as temperature. For example, MSCO-11, produced and sold by Higuchi, modulates between higher production of amylase at warmer temperatures and higher production of amino acids at the lower end of its temperature range.

While wheat and saccharomyces cerevisiae exist at the center of European culinary traditions, products fermented using koji are central to the culinary traditions in Japan and China, with miso and shoyu and rice vinegar and sake and mirin made through centuries-old practices playing a starring role. Though we do consume these products and though they are increasingly available in mainstream Main Street markets and grocery stores across the U.S., koji itself remains somewhat unknown in the Western Hemisphere.

Larder, Jeremy’s restaurant—which I could see from the front steps of the Ohio City apartment where I lived for years and spent weeks working from home under a stay-at-home order from the governor—infuses ancient traditions in the setting of a modern delicatessen, using koji to cure meats or vegetables more rapidly than more typical aging methods and with greater complexity and umami due to the mold’s production of amino acids. What Noma did to bring koji into a modernist, hyper-seasonal Scandanavian kitchen, Jeremy and his team at Larder are doing to bring koji into the old world style neighborhood deli (and like Noma, have earned accolades for doing so).

For our purposes, koji would serve as a processing agent—saccharifying polysaccharides and complex starches to make them available for secondary fermentation by other microbes as well as enzymatic processes within the coffee itself, while also producing glutamates that improve cup structure. No koji spores would end up in the final cup.

While koji starter is quite expensive (I just paid $250 to ship 350g of spores from Japan to Colombia, which would be enough to process 70kg of finished coffee), using rice and the methods found in Jeremy’s book, Koji Alchemy, a coffee producer could theoretically produce an infinite amount of koji for their needs—so while any process using koji could have a high initial cost, the ongoing expenses needn’t be as burdensome as those of processing using selected yeast.

Fermentation in coffee processing is typically pretty quick—often just 12-16 hours and perhaps up to 60. Compared with the years-long fermentations for shoyu or miso, or even days-long fermentation for sake, there is relatively little time elapsed between picking and drying. For this reason, when we inoculate coffee with yeasts, we select yeasts with a short lag phase: The quicker you build a biomass of your desired microorganism, the better your chances of crowding out competing microbes.

I knew from Jeremy’s book, eating at Larder and my own culinary uses of koji that a spore could grow to cover beets in a manner of days and koji’s effects could be detected by taste even sooner, but the conditions had to be right. We’d need to clean the cherry to knock back other populations inoculate heavily, and control the temperature and humidity to ensure the mold’s growth.

From months of conversations with Koichi-san I understood that his lab believed that growing koji on coffee cherry would be very difficult due to the rate at which spontaneous fermentation in coffee (e.g. rot) occurs and the diversity of competing microorganisms including other, aflatoxin-producing molds. His lab had success culturing koji on cacao, though—success replicated by Jeremy in the U.S. using some refrigerated, fresh cacao I sourced for him—so we suspected it could be done.

With the team at El Vergel ready to implement the process, Kaapo on board to use the results at WBC, and the support of Koichi-san and Jeremy, we used koji to process coffee.

Here’s how we did it.

Kaapo competed using the dry process protocol below (or—what I’m dubbing, wryly, the Koji Supernatural Process), of Java cherry inoculated with MSCO-11 koji. All documents related to the process, Kaapo’s roasting, and his presentation—including two additional processing protocols we trialed—are available for free and to all through this repository.

Special thanks to my dear friend Salomé Puentes for assisting in the translation of the processing protocol to Spanish and correcting my many, many grammatical errors.

Koji Processed Coffee

Equipment

You’ll need a few things to execute this well:

- probe thermometer

- digital ambient thermometer w/ humidity

- IR thermometer

- scale capable of 0.1g resolution

- platform scale (capable of weighing whatever batch size we’re working with, so 10 or 20kg or whatever)

- tarps (as flexible shade, if needed)

- Clean, cleanable plastic or steel paddles for turning coffee

- Potable water

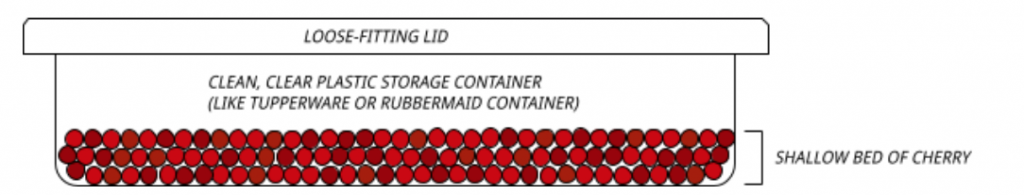

- Clean food-safe plastic storage container w/ loose fitting lid (like a rubbermaid or tupperware container that is big enough to hold a shallow layer of cherry)

- Fans (for increasing airflow during drying)

You’ll also need your microbes.

- For koji we’ll work with MSCO-11 from Higuchi-Moyashi in Japan. It has strong saccharifying effects with high amino acid production.

Before we begin

It’s critical that the cherry pile stay between 25-30ºC during the process or the koji will die. Conveniently, this is also the optimal range for any the yeast you’d use (typically strains of saccharomyces cerevisiae) as well as both cherry and parchment during drying.

You will use both your probe thermometer (stick it gently in the fermenting pile of cherry to check the core temperature before/after each mix) as well as your IR thermometer (to check surface temp and drying temps). If needed, move the pile in and out of shade to control the temperature of the fermentation.

For inoculating koji, you want a shallow layer of cherry so that there is enough airflow and there aren’t pockets of hot air. So you want something that looks like this:

We will also ferment in that same shaped vessel! It is shallow (meaning high exposure to oxygen, which is good because yeast produce the most metabolites with oxygen exposure—respiration is more efficient than fermentation) which will help to control fermentation temperatures and allow us to extend the fermentation to 36 hours and allow all of the tiny flavor and volatile aromatic molecules we created before to absorb into the seed through parchment.

Completely clean (and if possible, sanitize) every coffee contact surface. Coffee is a food—please treat it as such. Plus, we are playing with microbial fermentation and don’t want to introduce anything into the mix unintentionally.

You will be drying under partial shade (something that blocks 60-80% of light is perfect, we’re looking for temps of 25-30°C).

Cherry Selection

You’ll want a range of ripenesses from blood red to burgundy red ripe only. When receiving cherry, sort it for ripeness, and float it in clean, potable water to clean the cherry and skim off any floaters.

Dry Process (“Koji Supernatural Process”)

This is a 24-36 hour cherry fermentation that will be sent straight to drying. The goal is to culture koji on the surface of the cherry in order to break down polysaccharides and pectin as well as produce amino acids, which will result in a cup with more acidity and body than usual. Koji prefers high-humidity environments (it is, after all, a mold) so we’ll need to keep the cherry covered. Fermentation using koji produces a tremendous amount of heat so you may need to move it quite often to cooler environments.

- Place a clean, plastic fermentation bucket on the scale. Move your clean, floated cherry into it and note the final weight.

- Sprinkle 1g of koji spores for every 1kg of cherry in the bucket. So, for example, if you have 10kg of cherry, you’ll need 10g of spores. If you have 8kg of cherry, you’ll need 8g of spores.

- Gently mix the pile with either clean hands or a clean paddle, without breaking any cherry, to distribute the spores evenly.

- Record the date, time, ambient temperature, and the starting temperature of the cherry.

- Close the container with the lid (to preserve the humidity inside the fermentation environment).

- Check the temperature of the cherry pile using the probe thermometer every 6 hours and if needed, move the fermentation tank into a cooler environment, out of the sun, into shade, etc. Record the date, time, ambient temperature, cherry temperature, and aroma as well as your corrective action (moving the coffee, stirring, etc.).

- Stir the pile gently at least every 12 hours; if the pile is getting warm, stir it after moving it.

- You can also add small pieces of ice to gently cool the pile if needed. Stir to integrate after adding.

- Anywhere from 24-36 hours after beginning your fermentation, the koji should have grown to cover the outer surface of all of the cherry. It will look like white fuzz and should smell extremely tropical.

- At that point, the fermentation is complete and you need to move your coffee to dry.

Drying

We will be controlling the drying using weight and shooting for a final moisture content of 12.5-13%. This is not a stable final moisture content; it will fade quickly. However, we will be moving the coffee out of country quickly and storing it vacuum sealed in cool temperatures which will slow degradation. Higher moisture content coffee tends to pop more on the table and will be more intensely flavored owing to a faster rate of reactions during roasting and higher internal seed pressure.

General Principles

- Dry on clean raised beds to encourage airflow. If you must dry on a patio, put a clean plastic tarp down.

- Cover the coffee with shade cloth. This will protect it from the heat of the sun and will also protect it from rain, which is the enemy.

- Day and night cycles are important. Moisture needs to move in/out of the seed’s cellular layers to homogenize during the drying process to prevent a need for resting in parchment.

- You want to keep the coffee from dropping below the dew point temperature but also want to make sure the coffee is never hotter than 30ºC. That’s especially important for cherry drying. Shoot for a range of 20-30°C at all times.

- Use airflow! That’s what the fan is for. Moving air will accelerate the drying process without needing to increase temperatures and will prevent dew from building up on the cherry at night.

- When the coffee reaches 16-20% moisture, begin to collect the cherry at night and put it in a pile and cover it or place it in a (clean) bag or closed container to homogenize at night.

- Shoot for 20-30 days for cherry.

Drying Process

To begin, weigh your coffee.

- If the coffee is cherry, assume 65% of the weight is water.

- If the coffee is pulped, assume 45% of the weight is water.

The dry matter of the coffee will remain constant. So, the remainder of the weight (35% for cherry, 55% for pulped) is dry material. From there, you can calculate your target finished weight.

Cherry

Let’s say we’re working with 10kg of cherry:

- 65% of the weight is water (6.5kg) and 35% is dry material (3.5kg)

- So when the coffee is dried to 12.5%, we know that 87.5% of the final weight will be dry material, which remains unchanged.

- The amount of dry material is 3.5kg so we simply divide 3.5 by its percentage of the total final weight (87.5%):

- 3.5 / 0.875 = 4 kg

- Thus, when the cherry weighs 4kg, we assume it is 12.5% moisture content.

When it’s milled, we can check the moisture content. Let’s say we find it is actually 13, then we can work backward to find the starting moisture content:

Step 1: Weight dried sample

Step 2: Subtract weight of moisture from total weight and deduce dried matter weight.

Step 3: Subtract this amount from starting weight of sample, and that gives you the percent of the starting moisture

Dried Cherry Storage

If it will not be milled immediately, store the dried cherry in clean, closed GrainPro or Ecotact bags (or in the clean, sanitized, dry fermentation containers we used above with the lids closed tightly) and away from heat, moisture, and light. This will also allow the moisture content to continue to homogenize. Ideally it should be stored below 20°C at 50-60% relative humidity. Parchment can also be vacuum sealed if that’s an option.

Dry Milling

Do not polish the green coffee. Keep as much silverskin as possible; polishing creates friction that damages the resulting cup.

Separate by size, if possible.

Green grade to zero defects.

Immediately vacuum seal after milling.

BONUS: Cascara Miso

250g koji

25g kosher salt

250g cascara

Add the koji and salt to a medium mixing bowl. With clean hands, mix them together until they’re evenly distributed. Mix and squeeze the salt and koji together, breaking down the koji into a paste as much as possible. Add the cascara and mix thoroughly. Pour the mixture into any non-reactive pint container (such as a Mason jar). Store at ambient temperature for 2-4 weeks.

BONUS: Cascara Amazake

- Combine 1 part cascara, 1 part koji, and 2 parts water.

- Blend to increase the surface area of the cascara.

- Hold between 55-60ºC for 10-14 hours.

- Store airtight under refrigeration.

This should be sweet, acidic, and very fruit-forward with the flavor of the coffee pulp present.

If you’d like, you can then strain the solids and inoculate it with yeast (INTENSO is great) and ferment it in a clean, sterilized container with an airlock for 7-10 days to turn this amazake into an alcoholic wine. Rack, refrigerate, allow the lees to settle, and rack a final time before chilling to condition.

The recipes for cascara miso and amazake were adapted from base recipes in Jeremy Umansky’s book, Koji Alchemy.

Roasting

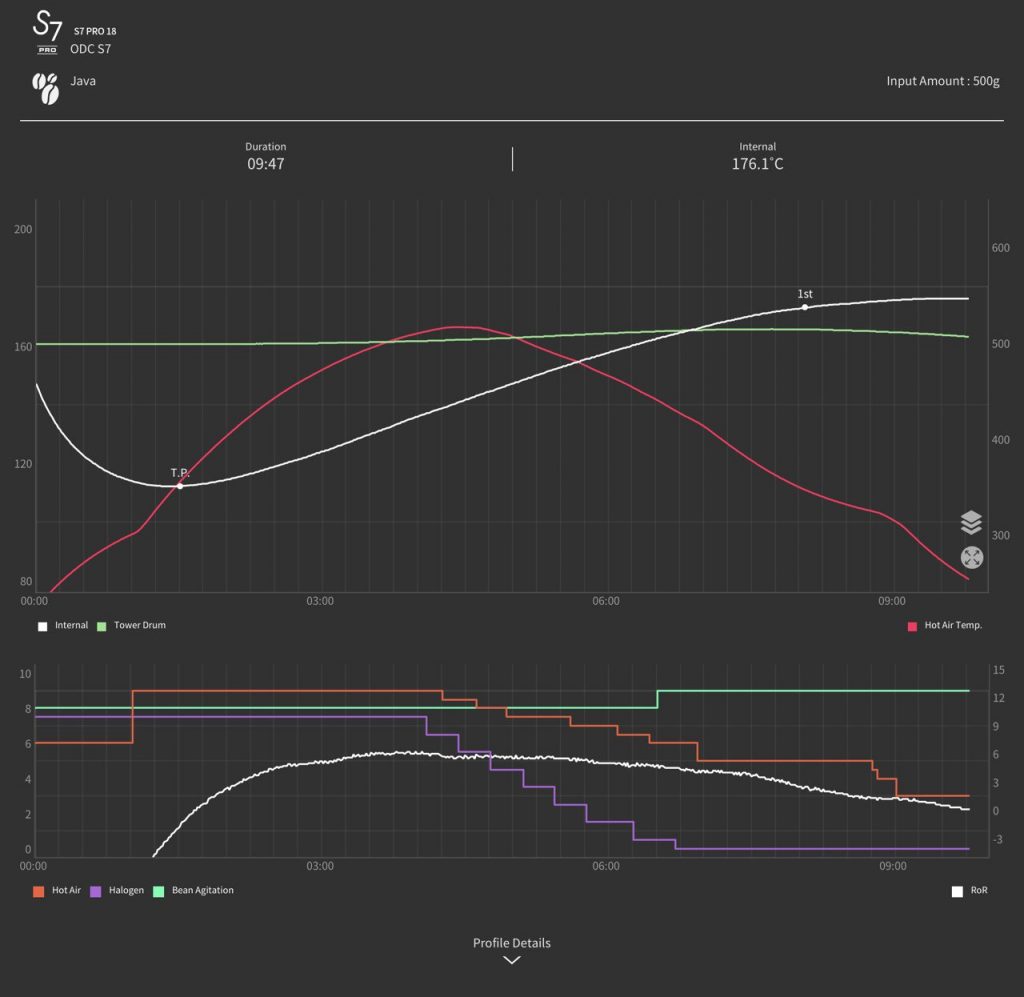

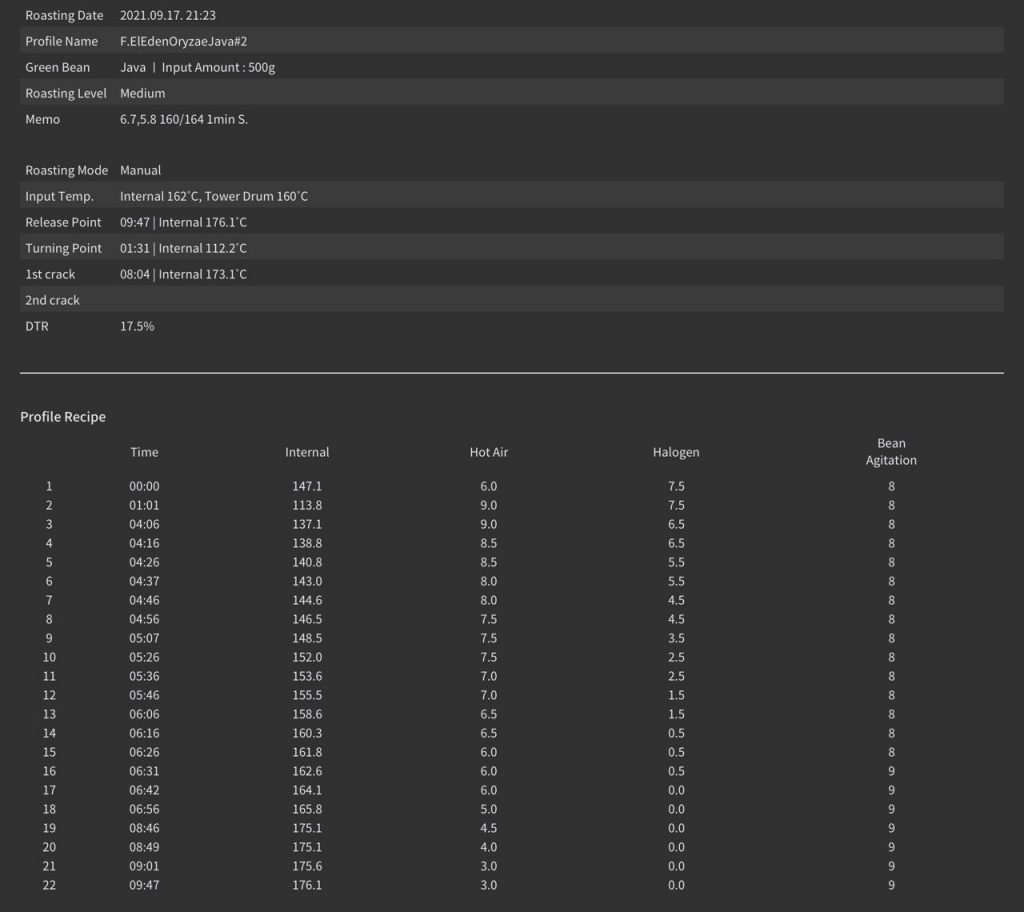

For his presentation, Kaapo roasted the koji-controlled cherry-fermented Java on a Stronghold S7 Pro coffee roaster. The Stronghold is a fantastic piece of technology—with a convective roasting environment and the ability to use halogen heating to provide finer control and more stability to the roasting environment, the automation in the machine is state-of-the-art and works well for situations that demand high precision, such as roasting for competition.

Here is the profile he used:

If you’ve read my piece on roasting on Lorings, you’ll recognize the “gas pyramid” roasting method—by applying heat in this way, Kaapo was able to create a consistent environmental temperature and produce exceptionally sweet, clean coffee while maximizing fruit and structure.

For those using a Stronghold roaster, you’re able to download Kaapo’s profile from Stronghold Square.

Post Script

When Kaapo read through the draft of this post, he noted that he thought it would help bring it to a close if I wrote, briefly, how I thought this processing protocol might improve economic conditions for coffee producers.

The truth is—I don’t.

Processing is a transformative step of the value stream, to be sure. Quality isn’t energy—during processing, quality can be created, maintained, or destroyed. But even though we value cup quality, does that value actually translate to economic security?

And what of boutique lots, exotic varieties, and experimental processes—such as koji processing? We’ve seen an explosion of planting of Gesha, Tabi, Pink Bourbon, Rume Sudan, and other exotic varieties in the last 4-5 years, just as we’ve seen an increase in the number lots marketed as superhoney or anaerobic or carbonic maceration or yeast-controlled or natural-hydro-honey—to name a few.

[Suffice to say that my pet name for this koji process is a not-so-subtle way of gently poking fun at one of alternative processing’s most prominent voices]

The market for these coffees has developed such that I can now talk to just about any specialty importer and within a few business days cup through a battery of anaerobic coffees. But as these coffees have come available, has the welfare of coffee producers fundamentally changed?

Has the calculus of global commodity trade been short-circuited by their mere existence?

While, certainly, some producers with the access to market and appetite for risk have leveraged these experiments to fetch higher premiums on those lots (a worthy endeavor, to say the least), that’s a fraction of the market and typically just a fraction of a producer’s production. For every success, how many product failures can a producer endure?

Do the majority of coffee lovers around the world even like coffees or want to drink coffees that taste like pomegranate kombucha—or in the worst case, uncontrolled rot and compost tea?

If the majority of coffee consumers don’t value these lots or their weird the same way that specialty roasters prize them, then so what?

I spoke recently with Tim Heinze of Sucafina, who as part of his work with CQI is exploring whether we need to develop a different standard for evaluating experimental lots. We talked back and forth about it (I personally don’t believe that they need a different score sheet or score system) but landed on a truth: even though they occupy airtime on Instagram, at WBC, and in high end roasteries across the world, so-called “experimental processes” make up far less than 1% of the total coffee supply.

Will the 1% save the world? (paging Anand Giridharadas here)

There’s a compelling case to be made that there is a place for boutique processing the value stream and in the portfolio of coffee producers. The protocol we designed and that Kaapo used is one that Elias Bayter of El Vergel said was one of the easiest experimental processes he’s ever executed—it required no more complexity than a typical temperature-controlled cherry fermentation and careful drying.

With a guaranteed buyer at a high premium ($55 per pound for a lot size of 16.2 pounds), there was no risk for the team at El Vergel. We learned something new, we produced delicious coffee, and we found a new, replicable way to achieve quality coffee with less effort and less ongoing costs than those required by other methods or microbes.

We wanted to produce a coffee that took everything we loved about classically processed coffees—clean, bright, structured, uniform, with elegant and well-integrated and balanced fruit tones—and amplify it. We weren’t setting out to create a “new” profile—we were trying to elevate a coffee that was already exceptional. We wanted to create a protocol that required less water, could be replicated anywhere, and that tasted like everything we love about washed coffees, but turned up to 11. And to that end—we succeeded.

It’s a new process, but it’s really just a play on the old—a rebrand with a funny name and a little sprinkle of fuzzy glitter on the outside of the cherry.

So while I don’t think we can change the world with a bit of koji, it is our hope that in publishing the protocol we used—complete, transparently, and in full—to produce a competition coffee, more producers would have access to auction or competition prices and we could upend the trend we’ve seen in recent years where access to competitions seems restricted to just the same four or five farms that are represented each year.

We’re not here to set up quasi-official sounding “Codes of Conduct” for coffee production, or to sell you our services, or to stand at the gate checking lots for certificates of analysis: we’re here to blow the gate off its hinges. The protocol we devised requires no special equipment or training and can be implemented at any farm, anywhere in the world.

Small, toy lots like this one allow producers to learn more intimately how to refine the coffee they produce and produce coffee more intentionally, or by creating a distinctive cup to help address or harmonize quality issues that might present more loudly in more conventional processing practices, or fetch a premium at auction to bolster investments elsewhere in the farm. But ultimately, unless a producer is able to find ways to diversify their revenue, improve agronomic conditions, implement agroforestry practices to create resiliency for climate change, own their means of export or otherwise broaden their access to the market—it’s just another day on the C-market.

A broken system that can only exist by extract value from countries that are—through a legacy of colonialism—specialized in producing raw materials for wealthy consuming nations is and will remain unjust. Producing countries, in this system, remain in service of wealthy consuming nations, regardless of how shiny we make those raw materials with koji or by suffocating them in a closed barrel.

If we want to fix the economic system of coffee, finding better ways to produce coffee is only part of the equation: if the roots of a tree are rotten, you might get through the year with some yield—but to sustain, you’re going to need a new plant.

I encourage everyone to pick up a copy and read Karl Weinhold’s book, Cheap Coffee.

Tags: coffee fermentation green coffee higuchi jeremy umansky kaapo kaapo paavolainen koji larder one day coffee processing transparency wbc

Fantastic read as always, cheers Christopher. Just curious if you are aware of the comparative characteristics of protocol #2 and #3 as I gather Kaapo used just protocol #1 for his performance. Thank you

Hey Andrew! I actually thought the washed sample had a ton of promise — I scored it just below the dry process version. I hope to run that protocol myself this year—I found out after the fact that rather than using a yeast selected for coffee fermentations (I provided a list) the team had used a bread yeast—not exactly what I’d called for, to say the least!

Haha, we’ve experienced the bad end of quite a few bread yeast fermentations.. Not to my taste either! Yes to using the appropriate yeasts anyway. Love to compare notes down the track, I’m also shooting for a washed protocol trial this year. Grateful for your open source Christopher.

I had Pink Koji roasted by Karma Coffee in Slovakia. It was very strange, so i looked into what it means koji ferment and found this article. Very interesting read. Fun experiment, fun taste in cup.

Glad you enjoy it.

Michal from Karma

Hey Christopher, just stumbled across your writings when doing a quick search for koji and coffee out of interest. Thank you for open sourcing the process and such great details. I’ve only recently gotten back into koji making and we also grow our own coffee (this year will be our first decent harvest) but just on a homestead scale in a sort of simple syntropic system. Think I will learn lots here, thank you.

Cheers

Leon